Since the virtual “discovery” of the original American Soccer League by historians like Colin Jose in the mid 1990s, that circuit’s decade of 1921 to 1931 has been referred to as the Golden Age of U.S. soccer — the era that gave us teams like Fall River Marksmen and Bethlehem Steel, players like Archie Stark, Billy Gonsalves, Bert Patenaude, and Dave Brown, and the foundation for the 1930 U.S. World Cup team that finished in third place in Uruguay.

Alas, the Golden Age was not so golden for Philadelphia. Sure, Philadelphia F.C. won the first ASL title in 1922—but that team was actually Bethlehem Steel. The following season saw a “real” Philadelphia team finish dead last with a 3-20-2 record, and 1924 saw a slight improvement to 5-18-2. A truly abysmal season followed in 1924-25 (2-34-6), and 1926 saw the Quaker City XI stagger in at 8-33-3. Philly finally broke double digits in wins in 1926-27, but still finished in dead last at 11-29-4 In sum: a horrific 29-134-17 in five seasons.

Nevertheless, there was much optimism in the City of Brotherly Love prior to the 1927-28 season, and a hope that Philadelphia could join Fall River, Bethlehem, Boston and New Bedford as contenders for the league crown. This is because, with the arrival of new ownership, came a new team, loaded with top foreign stars: Philadelphia Celtic.

Unfortunately, in typical Philadelphia style, the whole thing was a disaster. The story — with “ethnic marketing,” and a league takeover of the club — also has a fairly modern feel to it, as well.

The wily raconteur

The brains behind Philadelphia Celtic was one man, Irishman Fred Maginnis. Based in Brooklyn, NY, Maginnis was a moderately successful businessman, and eager to get into the pro soccer business. He purchased the Philadelphia ASL franchise in late 1926, and set about implementing his grand plan: putting together a team of Irish all-stars to represent his side.

The Philadelphia Celtic story would reveal Maginnis to be a colorful — indeed, shady — raconteur. However, it is nearly impossible to find details on the man. This is primarily due to the rather loose spelling of Irish surnames in that era — while the man himself spelled it “Maginnis,” it was also spelled as “McGinnis” and “McGinnes” in press reports. Among other mysteries: why was a Brooklynite so intent on owning a team in Philadelphia soccer franchise…but operating it out of Brooklyn? (The “Philadelphia Football Club”’s business address was 815 56th Street in Brooklyn).

A flight of earls…and footballers

Given his surname, it is easy to see Maginnis’ allegiance to Irish players. Whether he thought this would be good marketing, a la Chivas USA (although we now know how the modern attempt was a dismal failure), or was just national pride is unknown to us. What is clear, however, is that he cleaned house at Philadelphia F.C. shortly after the 1926-27 season, retaining only three Irishmen obtained during the season: wing half Billy Pitt, right back Hugh Reid (already in the ASL and obtained from Springfield), and utility-man Mick McGuire.

Billy Pitt’s acquisition was key for Maginnis. The Belfast-born winger had many contacts in both Northern Ireland and Ireland proper, and would return to the auld sod in the off-season to round up players. Offering players free passage and the princely sum of $55 per week, Pitt was able to secure top Irish and Northern Irish talent.

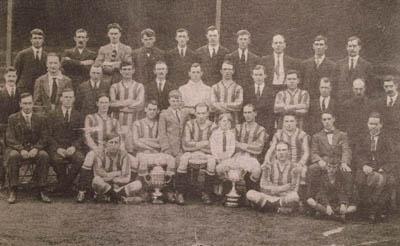

1922-23 Shamrock Rovers, Irish Free State winners. Future Celtics Dinny Doyle (seated on the ground, front left) and Bob Fullam (seated first row, third from left)

Among the players obtained by Pitt were two stars from the Irish Free State’s top club, Shamrock Rovers — wing half Dinny Doyle and center forward Bob Fullam, both Ireland internationals. He also grabbed (Northern) Irish League veteran Arnold Keenan from Glentoran (who, forty years later, would play as “Detroit Cougars” in the United Soccer Association) and inside forward Jimmy McAuley from Ards in the Irish League.

A big secret

While Maginnis would tell all who would listen that he was assembling a crack Irish squad, the actual acquisitions were shrouded in secrecy. So much so that, in its pre-season review, Soccer Pictorial Weekly’s Sam MacLerie could only write:

Beyond the fact that I cannot figure seriously the prospects of the Philadelphia and Hartford clubs, I am unable at this writing to discuss seriously their prospects for this season. Fred MacGinnes, the Philadelphia magnate, told me a few weeks ago that he has sixteen new Irish players over here ready for the start of the League season…May be [sic] he is planning a real surprise. His first game is with [J&P] Coats [of Pawtucket] and the next with Hartford, and in these two games, the real strength of his outfit will be fittingly tested.

Nevertheless, by the season opener, Maginnis did, in fact, have a team. His club was also entered in the U.S. Open Cup (pro/rel conspiracy theorists should take note that ASL teams like Bethlehem and Philadelphia received early round “exemptions.”)

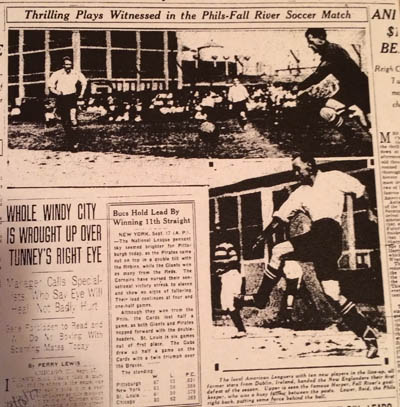

Philadelphia Celtic dropped its opener to J&P Coats and tied the Hartford squad, but impressed along the way. The team served notice to the rest of the circuit in its home opener, defeating the powerful Fall River Marksmen 5-3 at the I and Tioga Street grounds.

A league-owned debacle

Front page of Inquirer sports section after win over Fall River, Sept. 18, 1927. Celtic right back Hugh Reid is pictured in the lower right.

Alas, three games into the season trouble was brewing. Because Maginnis “failed to keep good faith with the American League officials,” the ASL took over the team, and instructed Maginnis to find a buyer within a month. Apparently, Maginnis was cash poor and not making payments to players from the start.

The team won its fourth match, over Boston, but had the result overturned by the league a week later because of an improper substitution. The absence of an actual manager no doubt contributed to the folly. However, the fact that the club was widely known to be broke so early in the season was far from a good sign, especially as the club was well-supported by Philadelphians, at least according to Soccer Pictorial Weekly: pointing out the crowd of 2,360 that attended the Boston match, the magazine noted “if a properly managed club cannot subsist on that there must really be ‘something rotten in the State of Denmark.’”

Something rotten, indeed. Although Maginnis was under orders to sell the club, he was deliberately over-valuing the franchise, spurning local offers to purchase the team. In the interim, the club was being operated by the ASL who, obviously, also thought it “owned” the players because it was paying them.

Fall River…Celtic?

Maginnis thought otherwise. Figuring that, while he may not control the team he at least controlled the players, on October 11, Maginnis sold all of the Celtic players to Sam Mark, owner of the Fall River Marksmen, one of the league’s top teams.

Predictably, this was not well-received by the ASL, and it immediately announced that the sale was “not sanctioned,” and that all of the players were to remain with Philadelphia. Not surprisingly, the Celtic players — owed money for several weeks — threatened to just walk out and go back home.

Predictably, this was not well-received by the ASL, and it immediately announced that the sale was “not sanctioned,” and that all of the players were to remain with Philadelphia. Not surprisingly, the Celtic players — owed money for several weeks — threatened to just walk out and go back home.

The Inevitable End

The ASL had had enough and on October 18, 1927, the league folded the club. ASL Commissioner Bill Cunningham stated: “The players of the former Philadelphia team are henceforth free agents so far as the league is concerned….There is no provision in the league by-laws for the permanent operation of a team by the league; neither is there any financial appropriation to cover the possible deficit of such a venture.” Cunningham lamented the dissolution of such a “splendid team,” and — in an obvious parting shot at Maginnis — hoped for a fresh start in Philadelphia “in the hands of reputable Philadelphia businessmen who have the future of the game at heart.”

At the time the plug was pulled, Celtic was sitting at 2-7-1 — not great, but understandable under the circumstances. The side received universally glowing reviews for its play, however: “splendid,” “clever Irishmen,” and so on. One wonders how the team might have thrived if not so woefully mismanaged from the start.

Some Celtic players did remain in the ASL. For instance, Reid signed with Bethlehem, while Doyle, Keenan, Pitt, and McAuley landed with Fall River after all. McAuley had an outstanding Open Cup run with the Marksmen in 1929-30, scoring 9 goals in six matches. Goalkeeper Alex McMinn signed with New York Nationals.

Although a Philadelphia team would be in the league the next season, it was more of what had preceded it: a bad team. Within a few years, the original ASL itself would be gone.

Sounds like various NHL teams!

Hi Steve. Sorry I just saw your comment. My email address is emd1969@aol.com. If you could send me some info on the little giant. I have a lot of stuff hopefully it’s something new. I played in the usisl for the philly freedom back in the 90’s. I guess your from the philly area.

Thanks

Ed