More than in any other country, professional sports takes up a huge place in American life. As the recent Super Bowl™ reminds us, the annual professional gridiron football championship has become an unofficial national holiday, with millions of people grinding their daily lives to a halt in order to watch the big game.

Our fascination with sports goes beyond events like the Super Bowl™. We are fascinated by the teams, and the players making up those teams. Further, that fascination extends to the history of each respective sport. Dozens of films, hundreds of books, and thousands of hours of conversation in bars and living rooms have been devoted to such age-old questions as “was Jordan better than Wilt,” “is today’s NHL weaker than the ‘Original Six’ era,” “could Jim Brown run for 2,000 yards in today’s NFL,” and “are the 1927 Yankees really the greatest baseball team ever”?

The American dilemma

Notably absent from such discussion is anything about U.S. professional soccer. It’s not for lack of history: professional, “Division 1” level soccer has been played in this country off and on since the 1920s. However, the lack of any “lineal history”—that is, the teams we know today don’t go back beyond 1996—coupled with the virtual absence of any film or statistics to refresh recollections make it difficult to wax nostalgic about pro soccer. Stated another way, you might actually be interested in a documentary about Eddie Shore, even if you only know him as a punch line in Slap Shot, because he at least played for the Boston Bruins. Your familiarity with the Bruins makes the subject more interesting, because you can then compare Shore to current and past Boston stars, and this, in turn, generates discussion about “all-time Bruins” teams and such. There is an unbroken link to the past. Conversely, a mention of Archie Stark might interest someone because of the sheer brilliance of a 67 goal season, but you have no way to link that feat to anything that is around today, because Bethlehem Steel FC is long gone.

Notwithstanding this permanent disconnect, those who are familiar with articles on the Philly Soccer Page know that we are soccer history nuts, and are always happy to post lengthy articles about the great teams and players of the past. Judging by the comments these posts receive, readers enjoy them, too. Still, the same problem remains: there is a disconnect between then and now, without a common kit to link the experiences.

Obviously, U.S. soccer’s broken and erratic professional history cannot be changed. However, I have long tried to find new ways to make history relevant for soccer fans by trying to create a “link” like other sports enjoy. While the Philadelphia Atoms are not the Philadelphia Union, both teams are a part of the city’s soccer history—along with Philadelphia Celtic, Philadelphia Nationals, Philadelphia Americans, and the Philadelphia Ukrainian Nationals. The same goes for other cities. We have had three major professional leagues in this country—the original American Soccer League, the original North American Soccer League, and Major League Soccer. Even though there is a 35 year break between the first two, and a 12 year gap between the NASL and MLS, there must be ways to bring them together in a way that will give U.S. soccer fans some sense of a “link,” even if somewhat manufactured, that will allow a deeper appreciation of our soccer history.

Moving the goalposts—stats to the rescue

As noted, I have long had these ideas in mind. And it was with these thoughts in mind that I came across Moving The Goalposts, by Rob Jovanovic (Pitch Publishing, 2012). The author himself, after noting the obvious influence of Bill James and Moneyball on all sports, says:

Moving The Goalposts hopefully provides a refreshing look at the aspects of [soccer] that have previously been overlooked, ignored, taken for granted or just plain misinterpreted. It aims to uncover numerous hidden truths about the game and explain why certain myths survive to this day….

The book itself makes wonderful use of statistical analysis and, even bearing in mind the famous maxim “lies, damned lies, and statistics,” makes a pretty compelling case for its various theories. (To find out what those are, exactly, you’ll have to buy the book.)

Not surprisingly, the book is Anglo-centric, focusing primarily on English football. However, a number of the concepts are easily applicable to American soccer, if only someone had the data….

Oh, yeah…that’s where I come in. I do have the data!

Lining the field

So, hoary old media guides, Graham Guides, Spalding Guides, and Colin Jose books in hand, I set out putting together a database that would allow me to start applying MTG principles to American soccer. As we’ll see, the results are surprising…and may get some Eurosnobs off of MLS’ back.

First, some background. American leagues have been all over the map concerning how champions are crowned. As we know, MLS has a playoff system—but at least nods toward acknowledging a “single table”-type champion with the Supporters’ Shield. The NASL also used a playoff format—but also awarded points on a 6-points for a win, one bonus point for each goal scored up to three per match system. The ASL went with winning percentages to determine champions many years, largely because of many teams’ inability to complete their fixture lists because of weather (note: the ASL was a “traditional,” fall/spring league, based in the northeast). With very few exceptions, none of these leagues played balanced schedules.

Against this backdrop, my first task was the “standardize” all of the league tables from 1921 to date. To do this, I eliminated divisions and conferences, and awarded the standard points for wins and losses for the era (i.e., 2 points for a win before 1995, 3 points for a win after; the FA started awarding 3 points per win in 1981, but I followed FIFA rules throughout). Also, as both the latter NASL and early MLS did not have ties, I had to go back and convert any overtime/”shootout” results to draws for the clubs.

Having put all three D1 leagues on as equal footing as possible, I was able to start applying MTG to U.S. soccer history.

Were the “Good Old Days” really good?

We’ve all heard variations on the same theme: “Stan Musial would have chewed up today’s pitching”…”Mario Lemieux would have scored 100 goals a year now that clutch-and-grab is out of hockey”…nostalgia always prompts us to believe that things were better in sports then than they are now.

I am just as guilty of this trope. I have long crowed that the 1920s were the “Golden Age” of American professional soccer (I’m not alone; Jose used “Golden Age” in the subtitle of his ASL encyclopedia), relying on little more than anecdotes, and stray facts like Archie Stark scoring 67 goals in 44 games in 1924-25.

Similarly, there are fans today that remember the original NASL, and will flatly state that the soccer there was so much better than in MLS.

So was soccer better then, or is it better today?

As Jovanovic notes, “better” is impossible to define—a better barometer might be “competitive.” So how does one determine “competitive”?

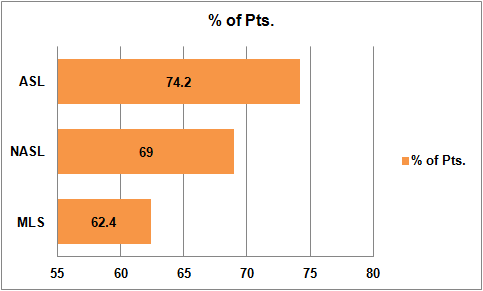

Jovanovic uses “percentage of available points won” as the basic scale to measure such things. Loosely translated, you can think “winning percentage,” although (because of the presence of ties) the two are not identical. Anyway, this percentage is useful because it takes into account such factors as different numbers of games played per season (and, as the ASL realized, is also useful when not every one of your teams is playing the same number of games), as well as the change from 2 points for a win to 3 points in 1995.

The graph above shows how the “league champions” (again, those who would have won a single-table league (think “Supporters Shield winners”), not necessarily the actual champions (i.e., playoff winners)) have won a fewer percentage of available points in MLS than in the other two circuits. This is not surprising. The ASL had relatively deep pockets, no salary cap and only one real competitor (the FA) for the world’s top talent, so well-funded sides like Bethlehem Steel and Fall River Marksmen could load up with top players and dominate. The NASL also had deep pockets, and no salary cap for most of its run, but had to deal with much larger global competition to secure players. Finally, MLS has had limited budgets and salary caps, enforcing parity.

So this tells us what we have long accepted as fact, right? MLS is a crap league, and the ASL is the standard that open leagues and pro/rel will give us (even though the ASL had neither). Case closed.

Not so fast. While it is clear league champions were more dominant in the “golden age,” this does not mean much if the dominance was the result of one team running roughshod through a bunch of weak sisters. The better question might be how competitive was the league as a whole. Stated another way, in which league is it harder to win points?

The Competitive Index

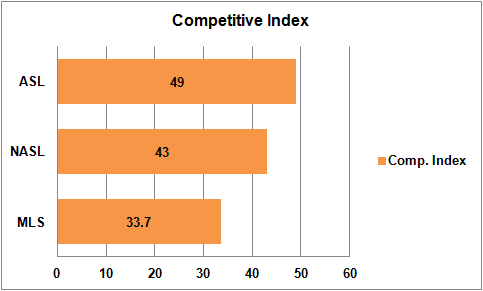

In MTG, Jovanovic devised a straightforward method of comparing the competitiveness of each league. With this simple measure, one could compare leagues from different decades which would take into account the different numbers of games played in a season and whether two or three points were awarded for a win. As he explains:

A basic, but telling, way of doing this is as follows. First, work out the percentage of points obtained by the champions and for the team finishing bottom of the table. By subtracting the latter from the former I got a figure for each division I decided to call, for no particular reason, the Competitive Index (CI). The most uncompetitive league would see the champions win every game, 100% of available points, and the last team would lose every game for 0% of the points so the CI would be the maximum 100%. Conversely, the closest-fought league would see everyone draw all of the games and be equal on 50% and so the CI would be 0%. In reality most leagues are somewhere between the two, usually between 30% and 60%.

So how competitive are/were the “Big Three” U.S. leagues”

As we can see, MLS’ attempts to achieve parity have been quite successful, as it is by far the most competitive of the U.S.’s three D1 leagues.

All told, however, all of the U.S. leagues have been fairly competitive, as opposed to other countries. For example, Jovanovic noted that the most competitive leagues in 2011 were as follows:

| Country | CI |

|---|---|

| Brazil | 35.1 |

| MLS | 38.2 |

| France | 42.1 |

| Russia | 45.6 |

| Argentina | 47.4 |

Conversely, Spain was the least competitive at 64, followed by Portugal (62.2), Scotland (59.7), Germany (56.9) and England (56.2).

Notice a trend? The leagues that tend to get glamorized in this country also tend to be top-heavy (EPL has the “big four,” while the others on the list tend to have a “big two” (at least in 2011—Rangers’ departure from the SPL will no doubt effect the league’s 2012 CI)), resulting in fairly non-competitive leagues as a result of the rich teams consistently getting richer. Meanwhile, MLS—largely by virtue of salary caps—is one of the most competitive leagues in the world and, given its overall average, has always been so.

While it is true that “competitive” does not necessarily mean “high quality,” it does provide fuel for debate: would MLS fans rather enjoy a league where everyone, in every given year, has a respectable chance of winning hardware, or would they prefer an EPL where only four teams will ever win anything? An interesting question, but one best saved for another day.

Returning to the U.S., let’s now look at what have been the most competitive seasons in our soccer history:

| Year | League | CI |

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | MLS | 17.8 |

| 1984 | NASL | 20.8 |

| 2002 | MLS | 22.6 |

| 1930 Fall | ASL | 22.6 |

| 2006 | MLS | 22.9 |

| 1997 | MLS | 26 |

| 2008 | MLS | 26.7 |

Not surprisingly, MLS dominates the list, and the two non-MLS entries are the result of historical quirks. The 1984 season was the NASL’s last, with the league down to nine teams after having 24 just four years earlier; the drastic retrenchment of talent, coupled with a salary cap, provided the U.S.’s second-most competitive season ever. Similarly, the ASL’s fall 1930 season was after the “Soccer War” and the collapse of several franchises as the result of the combined effects of the “war” and the Great Depression.

Least competitive seasons in the U.S. are as follows:

| Year | League | CI |

|---|---|---|

| 1922-23 | ASL | 66.8 |

| 1923-24 | ASL | 66.3 |

| 1921-22 | ASL | 63.3 |

| 1924-25 | ASL | 63.1 |

| 1925-26 | ASL | 60.8 |

Well, well—it turns out the “Golden Age” was staggeringly non-competitive, as the ASL’s first five seasons top the list. All things considered, this is not surprising: the early ASL featured giant sides like Fall River Marksmen, Bethlehem Steel, and New Bedford Whalers, but also included truly putrid sides like (the second) Philadelphia FC, and a lot of “one-season-and-done” teams who were easy pickings. This presents some interesting questions—for example, just how impressive was Archie Stark’s 67 goal season when it came in the rather uncompetitive 1924-25 season? Shouldn’t we be talking more about (Newark born-and-raised) David Brown’s 52 goals in 44 games for the 1926-27 New York Giants?

After 1926, the ASL’s competitiveness improved substantially, as teams settled in. In 1926-27, for instance, the CI was 51.1. For the circuit’s first five years, the average CI was 60.8; for the remainder of its existence, however, it clocked in at a much more respectable 30.1, better than MLS’ overall average of 33.7. Thus, it would appear that, to the extent the ASL represents U.S. soccer’s “golden age” at all, it was only during the five year period of 1925-31. Pretty thin gruel, and hardly enough to continue the pretense that 1920’s U.S. soccer was the best ever produced.

The new Golden Age

So what does all this get us?

While it may be boring, predictable, and generally lacking in star-power, MLS is giving us the most top-to-bottom competitive soccer this country has ever seen. This may not make it the “best” league ever, but it is certainly the one most likely to hold the interest of as many fans as possible, assuming those fans value trophies over aesthetics.

“Ok,” you might agree, “MLS is certainly ‘competitive.’ But the best teams ever produced in this country must be teams like the New York Cosmos, Bethlehem Steel, and Fall River Marksmen, right? And especially the Cosmos, right??”

Fair questions, as our current received wisdom tells us “yes.” But now that we have some data constructs, we can test the prevailing wisdom. We shall see in the next segment…again, however, you will be surprised.

Part 2 will be published on Wednesday.

Fantastic post! I really enjoy the quantitative approach, and look forward to the next installment.