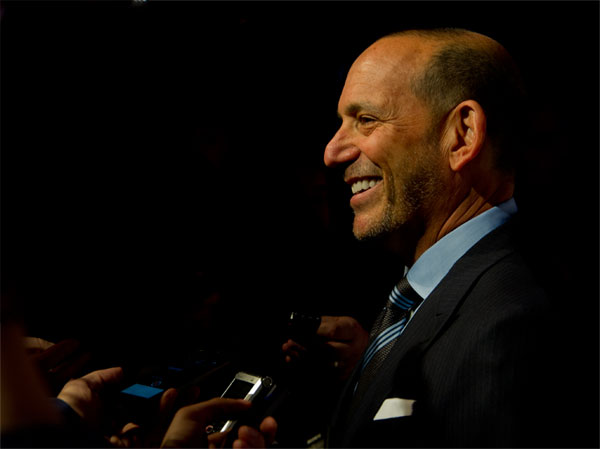

Photo: Earl Gardner

Fans of American soccer were hoping the annus horribilis that was 2020 would exit with a whimper instead of a bang. After all, a season of empty grounds and cheesy sound-effects and virtual tifos and even more Alexi Lalas than usual was more than most fans could bear. Haven’t we suffered enough?

Apparently not… as, on December 28, Major League Soccer Commissioner Don Garber took an action that has placed the 2021 season in jeopardy by uttering a seemingly magic incantation: force majeure.

With two Latin phrases in the space of two paragraphs, this must be serious…right?

It is. Very.

But before examining where we may be going, let’s revisit how we managed to get to this stage in the first place.

The 2020 Collective Bargaining Agreement

While it may seem a lifetime, it was only 11 months ago that MLS and the Major League Soccer Players Association reached agreement on a new, 5-year collective bargaining agreement. At the time, the deal seemed like a real victory for the players, who had been doing some serious saber-rattling about job actions and such. Under the agreement, free agency rights would increase dramatically, with the percentage of eligible players doubling. Salary budgets and player compensation were to experience steady growth that by the end of the deal will take the average salary over $500,000 and the senior minimum salary over $100,000. Also, the agreement included mandatory charter legs for team travel that grew incrementally during the term of the agreement.

So that was the deal, reached February 6. All was right with the world…all that needed to happen was for the players to ratify the agreement the MLSPA had bargained for them, a mere formality is most circumstances. As a result, there was not much urgency on the part of the MLSPA to actually get the agreement ratified.

And then the world changed.

With COVID-19 sweeping the country, MLS stopped playing games after March 7. More important, it advised the MLSPA that it wanted to change the terms of the deal—which is ordinarily not permitted, except for the fact that no collective bargaining agreement is final until it is ratified. In short, MLS saw a window of opportunity, and jumped on it. The deal was off, and the league wanted to renegotiate.

Understandably, the re-negotiations were pretty contentious. By June 3, however, the parties reached agreement on a “new” five-year deal…one which bore little resemblance to the earlier agreement. There were three major sticking points. The first two were basic enough: just how much of a pay cut the players would accept for 2020 (ultimately, 7.5%, less than the 8.75% the league sought), and how much of a reduction in television revenue sharing the players would receive (now 12.5% of the broadcast rights fee that was $100 million above 2022 mark in 2023. Originally, the players were to receive 25% of the TV fees; that figure would go into effect in 2024).

The third point was the most contentious: the league was seeking a force majeure clause. Such clauses are fairly common in “normal” contracts, and frees both parties from liability or obligation when an extraordinary event or circumstance beyond the control of the parties, such as a war, strike, riot, crime, epidemic or an event described by the legal term “act of God,” prevents one or both parties from fulfilling their obligations under the contract. Notably, most force majeure clauses do not excuse a party’s non-performance entirely, but only suspend it for the duration of the force majeure.

The thing is, you almost never see such a clause in a collective bargaining agreement, as it only serves to remove the very stability a CBA is supposed to provide. Nevertheless, MLS—perhaps noting even then how shambolic the U.S. government’s response to the pandemic had been—insisted on such a clause, and wanted to specifically include “lower attendance” as one of the force majeure factors. The players bitterly opposed. Ultimately, there was a compromise, and only a “general” force majeure clause was included.

Back in June, it was easy to suspect that MLS was just trying to exploit a bad situation and roll back what had been a historic deal. As the pandemic continues to rage into 2021, however, those suspicions are now moot.

Force Majeure

On December 9, Commissioner Garber announced that league revenues for 2020 were down by almost one billion dollars. This was due largely to the costs of having to house players in the Orlando “bubble,” as well as the extra expenses of having to charter players to matches. Of course, the greatly-reduced (if not complete absence of) ticket sales were a factor.

And, while sports owners are always willing to cry poor (for lots of different reasons), one could not help that Garber’s complaints had a ring of truth—the pandemic had caused lesser leagues (like the XFL) to fold or (like the National Lacrosse League) shut down their seasons entirely. Even the “Big Three” sports took a beating…but could at least rely upon significant television deals and such to ease the pain. MLS was somewhere in the middle.

Meanwhile, with the current administration’s continued mishandling of the pandemic still a factor (most recently in the realm of administering vaccines; while 20 million doses were promised by the end of 2020, only about 4 million have actually been administered), it is clear that restrictions on attendance at sporting events will continue well into the spring.

As a result, it came as no surprise to learn on December 29 that MLS was invoking the force majeure clause, citing the pandemic’s continued effect on league revenues

So now what?

Under the terms of the clause, the parties are to bargain over modifications to the existing agreement for a period of 30 days. If the parties do not reach agreement by January 28, then the collective bargaining agreement is terminated…which brings us to where we were a year ago.

The very real possibility of a work stoppage…which means a delay (at the very least) of the 2021 season.

The players certainly recognize that possibility. Understandably, the players are not chuffed over having to negotiate an agreement for the third time in the space of 12 months. Many were stunned by the league’s approach in May, seeking wage cuts from an employee group with many players only earning five figure salaries. Expect a real fight.

What does that mean? Well, we explained some of the potential scenarios when we were at this point a year ago, so feel free to refresh your recollection.

And buckle up.

(Erstwhile soccer historian Steve Holroyd is also the managing partner at Jennings Sigmond, P.C., a firm specializing in labor law and collective bargaining.)

Ugh… of course this would happen the year when the Union finally get into CCL.

.

I think the players still have the upper hand in all of this though. I don’t think MLS will push it to the point of a work stoppage.

Might not a delay in the new season be a good idea to give the country an extra month or two to get vaccinated? Not a longer delay than that, but hopefully the Biden administration will do a better job at getting the vaccines delivered.

Many thanks, Steve.

.

The link at the end to last year’s article on the subject is worth the time if you need refreshing on the basics of CBA’s, CBA’s in sports, and CBA’s involving MLS in particular.

.

.

Does anyone else feel like the entire sports industry is a a house of cards?

* “is a house of cards” (didn’t correct in time)

I’m not sure I’d call it that, but I would absolutely agree with a statement that went something like: most businesses are one or two bad months away from folding at all times, even the seemingly successful ones.

Thank you… that is a more thoughtful articulation.

You lost me after your 2nd political comment. If you want more readers here, save that “stuff” for your social media accounts.

Merely factual statements, with no blame assigned to anyone in particular. If that’s “political,” then I don’t know what to tell you.

Gotta admire your restraint. Facts suffice.

Many thanks, Steve.

The link at the end to last year’s article on the subject is worth the time if you need refreshing on the basics of CBA’s, CBA’s in sports, and CBA’s involving MLS in particular.