Our series on soccer’s origins in Philadelphia began with a look at the football traditions of the British colonists who settled the area, as well as the football traditions of the Native Americans they encountered. We continue with a look at football in colonial and post revolutionary Philadelphia.

Colonial football

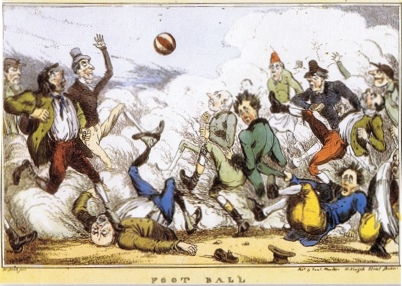

Just as had happened in Britain, the violence and disorder associated with the playing of football resulted in attempts to restrict it in Britain’s American colonies.

Puritan Boston issued an edict banning football from being played on the streets of the town under the pain of a fine of twenty shillings per offender as early as 1657. In Pennsylvania, The Great Law of 1682 forbade “Such rude & Riotus Sports & practices as Prizes or Stage plays, Masks, Revels, Bulbaits, Cock fightings with such Like” under penalty of at least ten days imprisonment at hard labor or a fine of 40 shillings.

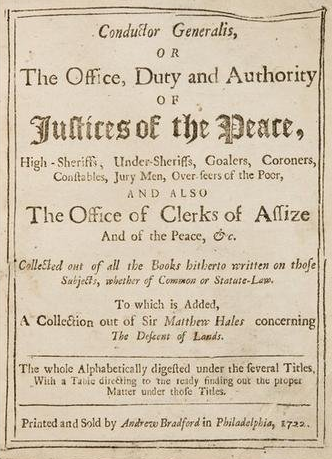

Conductor Generalis, a sort of quick-reference manual for Justices of the Peace, sheriffs, jailers and other enforcers of the law, was first published in 1711. In an edition published by Andrew Bradford in Philadelphia in 1722 under the heading “Games unlawful, and Gaming-Houses,” it is stated that officers of the law may “enter into any common Place where unlawful Games are suspected to be used: As Bear-baiting, Cock fighting, Football, Bull-baiting, Coits, Nine-Pins, Bowling, Dice, Tennis, Cards, are unlawful games.” The law applied to “Apprentices, Husbandmen, Servants of all Kinds, Artificers, Labourers, Fisher-men, Mariners, Watermen” — or just about everyone — and violators were subject to a 20 shilling fine. An exception was made for Christmas, “nor then, but in their own Houses, and Servants in their Masters Houses, and by their Leave.”

(Trying to give a sense of what 20 shillings would be worth in today’s currency is a tricky business, complicated by the fact that, in addition to British pounds, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania also issued their own pound currency, each of which was worth less than their British counterpart. In the event, 20 shillings made one pound. Using a simple calculation based on the percentage increase of retail price index, one British pound in 1657 would be worth the equivalent of £141 in 2013, the last year for which a conversion is available at measuringworth.com. That would be approximately $227.)

The long list of unlawful games contained in the Conductor Generalis is a fair review of the kinds of leisure pursuits that were available to settlers in Philadelphia little more than 40 years after the founding of the city. That such pursuits were considered unlawful is indicative both of the English common law tradition the colonists brought with them and of Pennsylvania’s Quaker and Presbyterian religious heritage.

The long list of unlawful games contained in the Conductor Generalis is a fair review of the kinds of leisure pursuits that were available to settlers in Philadelphia little more than 40 years after the founding of the city. That such pursuits were considered unlawful is indicative both of the English common law tradition the colonists brought with them and of Pennsylvania’s Quaker and Presbyterian religious heritage.

William Penn, the Quaker founder of Philadelphia wrote, “the Best Recreation is to do Good … Study moderately such commendable and Profitable Arts, as Navigation, Arithmetick, Geometry, Husbandry, Gardening, Handicraft, Medicine, &c,” a list that would be very helpful for the work of carving a colony out of the wilderness but one from which football is conspicuously absent. The sport historian J. Thomas Jable observes of the Quaker and Presbyterian influence on Philadelphia’s early cultural life, “Espousing industriousness and piety, both religious denominations detested idleness and frivolity which they associated with most sports and amusements.” As the population of Philadelphia increased and diversified, many Quakers moved their residences outside of the city to more rural districts “taking their sober customs and solemn behavior with them.” Though their influence may not have been as great as it once had been, it was nevertheless still present.

J. Thomas Scharf and Thompson Wescott write in a history of Philadelphia published in 1884 that “the Philadelphians were fond of many sports requiring strength or agility, especially outdoor sports,” but references to actual football games in colonial Philadelphia are difficult to find. Much easier to find are references to football that give a sense of its common place in Philadelphia’s cultural life.

Some Philadelphians chafed against the sense of propriety that pervaded social relations in the young city. A letter in Andrew Bradford’s the American Weekly Mercury in May of 1740 signed by one Tom Trueman wonders if

a Company of honest young Fellows should once a Fortnight at a proper Season of the Year meet and play a Game at Bandy-wicket, or Foot-ball, which are no very sinful Exercises, and they should be reproached as idle disorderly Persons by a Man who had no Taste for such Diversions; and two or three of the Company should take upon them to say the Person who reproved them was a Busy-body, and an intermeddler in other Men’s Matters; and that the Company were of the so bereft fort of young Men in Town, would it therefore follow that such an Expression could be construed to mean that there were no sober young Folks in Town?

So, not all Philadelphians — particularly “sober young Fellows” — viewed prohibitions against football as seriously as their “busy-body” elders. Written less than 20 years after the publication of the Conductor Generalis it would seem from this letter that football was being played regardless of secular law and religious senses of propriety.

That football was a self-evident part of cultural life in Philadelphia and throughout the colonies is further shown from references in other contemporary sources. An edition of the American Weekly Mercury published in March of 1740 contains news from London that includes mention of “Foot-ball” being played “on the Thames about Brantford,” perhaps providing a happy memory of the mother country for some homesick English colonist. References to football can be found in sources from other colonies. The Virginia Almanac for 1766 suggests if “thou play a match . . . at football . . . and break either an arm or a leg, then that is an unfortunate day,”

For tho’ they may be set, and heal’d again,

Yet e’er’ ‘tis done thou must endure much pain;

Besides the surgeon paid at a dear rate,

All which may prove that day unfortunate

It’s not just that one can get hurt playing football, getting hurt means one has to pay the doctor.

Football also appears widely as a metaphor. Bickerstaff’s Boston Almanack for 1774 contains a comic poem entitled The Wager. A man who bet that he would be married finds “I’ve won to my cost . . .”

A terrible shrew of a wife I’ve had to handle,

It was but last night in my face went the candle

She’s a scolding forever, no tongue can express,

She makes the room echo, like football, no peace

Be it an item in the news, a theme in a lesson on the need to be careful when at play, or as a metaphor in a comic poem, football would be familiar to Philadelphians.

Football during the Revolutionary War

By the middle of the 1700s Philadelphia was a prosperous economic center with a rapidly growing population. During the Revolutionary War, Philadelphia experienced a boom due to its importance as an economic engine for the machinery of war and as a center of revolutionary government. However, the British occupation of the city from September 1777 through June of 1778 resulted in a mass exodus of those who supported the revolutionary cause, and of the 21,767 people who remained in Philadelphia, Southwark, and Northern Liberties during the occupation, 17,285 were women, children, or adolescents.

Did the British troops play football during the occupation? I have not yet located any accounts to prove they did. But it would not be surprising if they did play football. As the British consolidated control of forts along the Delaware to open up access for the supply of goods by sea, they settled into a comfortable occupation of the city. Come springtime, troops were thirsting for leisure activities, and this is also the time of traditional folk football such as the Shrovetide football games back in Britain. But, again, we cannot say with certainty that football was played by the occupation forces.

In an essay on sports and games during the American Revolution, Bonnie Ledbetter says that football received very little mention in the diaries of American soldiers, although Nathan Hale was apparently a renowned player. Recalling the potential for injury resulting from the violence inherent in the football of the day, it would be understandable for officers to forbid troops from playing the game. The Continental Army had enough difficulty keeping up troop numbers without the possibility of incurring casualties in play.

Ledbetter says further that sports were informal and spontaneously played, and that she found no mention of people or groups organizing others for play. Officers would have been the natural source for such organization but given official disapproval of fraternization between officers and enlisted men as a possible cause for disrespect and insubordination, officers organizing troops to play football would likely have been exceptional. When one also remembers that on the playing field distinctions of class and rank tend to be forgotten, the relative absence of so potentially disruptive an activity as football becomes even more understandable in a young army struggling to meld militias and regular army units into an effective fighting force. Perhaps more simply, there was no tradition of instilling unit pride through organized sporting competitions against other units in the new Continental Army, something that would have been more familiar in the long established British Army.

There is a reference In Volume 16 of The Writings of George Washington that could involve football. The General Orders for Oct. 10, 1779 relate,

It was with surprise and concern that the General during the hours of exercise yesterday saw a number of men in their respective encampments. It was his expectation that all men off duty should be manoeuvred at the hours appointed. The want of shoes or other articles of clothing cannot be urged in excuse for their not being under arms because they were employed at games of exercise much more violent; He earnestly exhorts officers to attend closely to their duty and by their diligence and example prevent the nonattendance of their men. (Emphasis added.)

Is Washington referring to football when he describes that his troops “were employed at games of exercise much more violent” than the drill he expected them to be engaged in? We cannot know.

Football after the Revolution

References to football in Philadelphia newspapers continue following the Revolutionary War. A report in the National Gazette from August, 1792 of happenings in Turin based on French newspaper accounts describes “a quarrel” between a groups of students and “a body of artists and mechanics” over the rights of the students to play football, a quarrel that led to several days of disorder and resulted in martial law. The author compares the events to those in Revolutionary France and argues that the causes for the disorder lay “in the arts of the aristocracy” who are the “natural and avowed enemies” of the people, sentiments that likely resonated with readers in post revolutionary Philadelphia. The Independent Gazette described in December of 1791 the death of one M. Gagnon at the hands of a mob during the Haiti Revolution: after being killed, “his head [was] cut off, thrown into the air, with cries of vive la nation! and afterwards kicked about like a foot-ball.”

Examples of football as metaphor abound in Philadelphia’s post-colonial newspapers. In August of 1796, the Philadelphia Minerva noted that

Men’s zeal for religion is much of the fame kind as they feel for a foot-ball: Whenever it is contested for, every one is ready to venture their lives and limbs in the dispute; but when that is once at an end, it is no more thought on, but sleeps in oblivion, buried in rubbish, which no one thinks it worth his pains to rake into, much less remove.

In describing the results of the disputed presidential election of 1800, the Philadelphia Gazette describes in January, 1801 a conversation between “Two gentlemen” in which they agree that while the Democrats had gotten their man, Thomas Jefferson, elected, “it would not, such was their itch for slander, be more than three months before they would abuse him:—’It may be so,’ said the other, ‘for what does it signify to have a football, if we can’t kick it.'”

Throughout the late eighteenth century and through the nineteenth century, in scores of speeches, essays and articles, regardless of the issue at hand, the metaphor of football is employed: ideas, people, countries, all are “kicked around like a football.” But while it is easy to demonstrate that football was part of the vocabulary, knowledge, and discourse of Philadelphia’s citizens, it is more difficult to find examples that demonstrate that it was a part of their experience. That begins to change in the first half of the 19th century, particularly with school-based football.

The series continues later this week

I enjoyed this read- must be work to comb sources for these references.

Thank you, Ken. It is hard work, but I love it!

Love it Ed. Thanks.