On May 3, 1936, Philadelphia German Americans defeated St. Louis Shamrocks in the US Open Cup final. In doing so, they became both the first amateur team to win the Open Cup and the first team to win an Open Cup final in Philadelphia.

On Sept. 16, the Philadelphia Union will become the first area team to play in an Open Cup final since United German Hungarians’ defeat by San Francisco’s CD Mexico at Kuntz Stadium in Indianapolis in 1993, and the last to do so at home since Ukrainian Nationals defeated Orange County SC at Cambria Stadium in 1966 final.

Area clubs and the US Open Cup before 1936

While seven area teams entered the first edition of the National Challenge Cup, as the US Open Cup was then known, in the first edition of the tournament in 1913, Bethlehem Steel FC became the first area team to lift the Dewar Challenge Cup in the second edition of the tournament in 1914-15. Bethlehem would win the Cup four more times between that first championship and 1926, every time the team made it to the final except for the loss to Fall River Rovers in the 1917 final.

In all of those wins, the only time the team won at “home” was in their first win. Even that win didn’t occur at the grounds most associated with the team, Steel Field, which, when construction was completed a year later was perhaps the best US soccer field of the era. While East End Field in northeast Bethlehem was home before the completion of Steel Field, the team sometimes played big games at Taylor Field in South Bethlehem, home of Lehigh University’s American football team, and that’s where Bethlehem defeated Brooklyn Celtic on May 3, 1915 for its first Cup championship. After that, Bethlehem won the national championship in Pawtucket, Rhode Island (1916); Harrison, New Jersey (1918); Fall River, Massachusetts (1919); and in Brooklyn (1926).

After their final Open Cup win in 1926 over the Ben Millers of St. Louis — then the latest episode in a series of games between area teams and St. Louis teams that began with Tacony FC’s trip to the Mound City in 1911, followed by St. Leo’s visit to Philadelphia in 1912 and Innisfails visit in 1913, as well as Bethlehem’s trip to St. Louis in 1916 — Bethlehem would reach the Eastern Division final the next year, only to fall 2-1 in Providence to Fall River on April 24, 1927. The following year, Bethlehem lost the Eastern Division semifinal to Brooklyn Wanderers. In 1929, Bethlehem again made it as far as the Eastern Division semifinals only to fall to the New York Giants. Bethlehem made its final Open Cup appearance in 1930, losing the Eastern Division final over two legs to Fall River, the final game of which was played on March 23. On April 27, 1930, the team played its final game, the last Bethlehem goal being scored by the legendary Archie Stark in a 3-2 loss to Hakoah All-Stars in Brooklyn.

In 1931, Trenton Highlanders bowed out of the tournament after a 7-1 first round loss to Baltimore. The next year, Trenton defeated Philadelphia’s Fairhill club 4-0 in the first round before being eliminated by Newark Americans in a 2-0 loss in the second round.

In 1933, Trenton was eliminated in the first round. In Philadelphia, Fairhill faced Philadelphia German Americans. After a two-game series that included a 6-2 win in the first game on Jan. 14 in which Bert Patenaude — who with the US team in 1930 became the first player to score a hat trick in the World Cup — scored five goals, a feat that would not be repeated by a Philadelphia player in Cup play until the Ukrainian Nationals Mike Noha scored five goals in the 1960 final against Los Angeles Kickers, the German Americans would move onto the second round where they defeated Baltimore Canton 3-2, setting up an Eastern Division semifinal meeting with the New York Americans. Philadelphia German Americans would be eliminated in the two leg semifinal by the New York team, who themselves would be defeated in the tournament championship by Stix, Baer and Fuller of St. Louis, the team that lost the 1932 final to New Bedford Whalers.

No area teams played in the 1934 edition of the tournament. In 1935, Philadelphia German Americans were eliminated with a 1-0 loss to Baltimore Canton in the first round on March 3 in Philadelphia.

Philadelphia German Americans before 1936

Philadelphia German Americans was founded in 1924 by the Philadelphia German Rifle Club as First German SC. The team was often referred to as the Philadelphia Germans or Philadelphia German Americans, and the second name soon stuck.

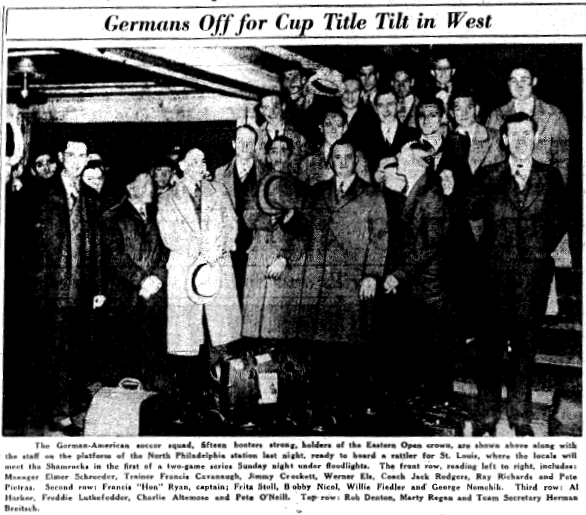

Beginning in 1932, the team was managed by Elmer Schroeder, a position he would hold through 1937. A lawyer by trade, Schroeder had been director of all teams in the Lighthouse Boys Club from 1917 through 1931. Schroeder’ expertise as an administrator led to him being named second vice president of the US Football Association (as the US Soccer Federation was then known), the position he held when he managed the US team at the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam, where the team saw a quick first round exit after a 11-2 defeat by Argentina on May 30, 1928. As USFA vice president, Schroeder joined the US team in Uruguay for the first World Cup in 1930, where the US advanced to the semifinals before being defeated by Argentina, 6-1, on July 26, 1930. In 1933, Schroeder became the first American-born president of the USFA, serving for two years. During that time he was also manager of the 1934 US World Cup team.

After building up a reputation as a local powerhouse in league play in Philadelphia, the German Americans gained notice on the national soccer scene by defeating Pittsburgh’s McKnight Beverage 5-1 on April 23, 1933 to win the National Amateur Cup. On April 21, 1934, they defeated Pittsburgh’s Heidelberg SC to claim the National Amateur title for the second year in a row. The first edition of the tournament had been won by Philadelphia’s Fleisher Yarn in 1924. In 1923, Fleisher Yarn had won Philadelphia’s Allied Amateur League title, the Allied Amateur League Cup, the Allied Amateur Cup, and the American Cup championship. The American Cup, the predecessor to the National Challenge Cup as the soccer championship of the US, was founded in 1885 and staged for the last time in 1924, when Fleisher Yarn was defeated in the quarterfinals by Bethlehem, who would go on to win their sixth and final American Cup title.

The success of the Philadelphia Germans Americans in the National Amateur Cup was instrumental in the selection of five of the club’s players — Bill Fielder, Peter Pietras, Francis “Hun” Ryan (who had played on the 1928 Olympic team under Schroeder), Al Harker, and Herman Rapp — for the 1934 US World Cup team. It probably didn’t hurt that the team was managed by Schroeder and coached by David Gould, who in 1897 played for the John A. Manz team, the first Philadelphia team to win the American Cup. The team’s trainer, Francis Cavanaugh, was also the trainer for the German Americans. When he coached the US team, Gould was in the midst of a long career as coach at the University of Pennsylvania, where Schroeder had played under him when Gould was an assistant coach. Defeating Mexico 4-2 in a play-in game in Rome on May 24, the US was knocked out of the tournament in its first game by a 7-1 loss to host country Italy three days later on May 27, 1934. (Group play had been abandoned that year in favor of a single elimination format). After the World Cup, the US team played four games against club teams in Germany where it finished with one win and three draws.

The German American team also gained international experience at home in Philadelphia. On October 21, 1933, the team hosted Audas SC of Chile, losing 8-3. On September 15, 1934, the team hosted Czechoslovakia’s SK Kladno, losing 2-1. On May 18, 1935, the team lost 3-0 to the All-Scotland team. (The team also won the World’s Fair Championship in Chicago in 1934 but I have so far been unable to find out if the team played domestic or international opposition, or both, to win the championship.)

While still an amateur team, Schroeder entered the German Americans in the newly relaunched American Soccer League for the 1933-34 season. It was an inauspicious first season, the team finishing last in the standings. With a core of World Cup veterans for the 1934-35 season, the team embarked on a remarkable turnaround, going from last place to first to win its first ASL title.

In the the 1935-36 season, the team was unable to replicate its first place finish, finishing fourth in the league. But, Philadelphia German Americans would finish the Spring of 1936 as champion of the United States.

National Challenge Cup Eastern Division First Round, March 1, 1936: Philadelphia German Americans 5-0 Budd AA

On Sunday, March 1, 1936, Philadelphia German Americans hosted Budd AA in front of 2,000 spectators for the Pennsylvania state championship at their North Philadelphia grounds, which were located at Eighth Street and Tabor Road and sometimes referred to as the Rifle Club Grounds or Tabor Field. As the state championship match, the game also served as a National Challenge Cup Eastern Division first round match, with the winner advancing to the division quarterfinals.

Budd AA, who were champions of the first half of the city’s National League 1935-36 season, were sponsored by the Budd Company, which was located on West Huntington Park Avenue. After becoming a major supplier to the automotive industry following its development of the first all-steel automobile bodies in the 1910s, the company branched out in the 1930s to become a major manufacturer of stainless steel passenger rail cars. Later, the company made the first stainless steel subway cars for the city’s Market-Frankford line.

While it was a mild winter matchday with a high of 42 degrees, the field was muddy after a rainy February. According to the Philadelphia Inquirer’s March 2 report on the game, the German American team was “at its best under these conditions.”

Budd put up a stubborn showing in the first half, the Inquirer reporting that the “industrial representatives did all the pressing in the early part of the game.” But it would be the German Americans who would score first, with inside right “Hun Ryan” scoring on the counter just two minutes before the end of the first half. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported, “Ryan, taking a cross from [George] Nemchik, pocketed his marker from 25 yards out with a caroming smash which glanced off the upright. [Budd goalkeeper] Joe Kennedy made a valiant effort to smother the ball, but he was too far out of position.”

With “power a plenty and stamina to spare,” it was all German Americans in the second half, with William Fiedler, Sam McAlees, Fred Lutkefedder and George Nemchik each tallying for the 5-0 win. For the German Americans, it was their fourth consecutive Pennsylvania state championship.

Interestingly, the box score for the game in the Inquirer report indicates that the German Americans used two subs, including goal scorer Lutkefedder replacing goalscorer McAlees, and Budd used one sub. The use of substitutions would not become an official part of the rules of the world’s game until 1958.

National Challenge Cup Eastern Division quarterfinals, March 15, 1936: Philadelphia German Americans 3-2 Baltimore Canton

Two weeks after defeating Budd AA, the German Americans hosted Baltimore Canton in the Eastern Division quarterfinal game on March 15 before what the Inquirer described as “the largest crowd of the year at the Tabor rd. field.” Founded in 1917, Canton had defeated the German Americans with a 1-0 upset win on March 3, 1935 in Philadelphia in the first round of the 1935 National Challenge Cup.

The game day high temperature of 69 degrees may have heralded the approach of spring but the field at Eighth and Tabor was again muddy after two days of rain only a few days before. In an attempt to level the field, a macadam roller had been deployed only for it to become stuck “in the mush at the north goal,” causing the start of the game to be delayed. George Butz said in his Inquirer match report of March 16, “The tractor was removed and that portion resembled a plowed up marsh.”

Once again, the visiting team came out aggressively in the early moments, but the momentum of play soon shifted back to the German Americans, who were bombarding the Canton goal with shots from distance. Still, it would be Baltimore’s Bill Schwanke who would open the scoring at the 30 minute mark when “a quick breakaway produced the setting for a picturesque scoring play.”

The Baltimore team would not hold the lead for long. The Inquirer report continued, “Hardly had the crowd settled when the Germans put over their first goal to deadlock things before the intermission,” with Ray Richards, “the Nanticoke blond” outside right, scoring the equalizer.

Soon after the start of the second half, the German Americans would put the game out of reach when a “”bang-bang’ sortie” saw Fiedler and Nemchik score two goals in a five minute span. “Pudgy” Al Nixon would get a goal back for Baltimore before the final whistle, but Philadelphia was on the way to the Eastern Division semifinals with the 3-2 win. Baltimore would go on to finish in second place in the ASL that season.

National Challenge Cup Eastern Division Semifinals, April 5, 1936: Kearney Scots-Americans 0-1 Philadelphia German Americans

Philadelphia German Americans would be on the road for the Eastern Division Semifinal, facing the Kearney Scots-Americans in front of 8,000 spectators in Newark on April 5. A strong breeze and an “extra-lively ball” would make play difficult, frustrating both teams. Moments after the opening kickoff, the German Americans almost conceded an own-goal but, mercifully, the ball rolled out for a corner.

The teams were soon trading scoring chances but good work from both goalkeepers prevented those chances from being converted. German American goalkeeper Rob “Rusty” Denton was hurt on one play “as the Scots forward wall charged” in on goal but was able to continue. Soon after, he was “banged again on a run,” only to soldier on.

The teams were soon trading scoring chances but good work from both goalkeepers prevented those chances from being converted. German American goalkeeper Rob “Rusty” Denton was hurt on one play “as the Scots forward wall charged” in on goal but was able to continue. Soon after, he was “banged again on a run,” only to soldier on.

It would be the Scots whose frustration would become manifest late in the first half. George Butz’s match report for the April 6 edition of the Inquirer described, “Moniz slugged Al Harker late in the half as the Kearney Plaidmen became infuriated when they couldn’t dent the cords. The referee soon settled this skirmish and the crowd fringing the field halted play by rushing out onto the pitch.”

The lone goal of the match would come from German Americans center halfback Peter Pietras, who unleashed a “30 yard liner” to tally what would prove to be the game winning goal. Butz described, “The play which gave the Philadelphians the win was well executed. [Left halfback Charlie]Altemose started it off on a throw-in to Ryan and the latter laid the leather to Pietras, who tore up and walloped the ball cleanly through George Davis’ outstretched hands. It was labeled from the second Pietras set his right boot on it.”

Out of the Cup tournament, the Scots would finish third in the ASL standings that season. But the German Americans were now just two games away from a National Challenge Cup final. In their way was ASL rival St. Mary’s Celtic of Brooklyn.

National Challenge Cup Eastern Division Final

Game One, April 12, 1936: St. Mary’s Celtic 0-2 Philadelphia German Americans

The Eastern Division final — essentially a semifinal series for the 1936 National Challenge Cup final — would be played over two-legs with the winner decided by the highest aggregate score. For the first game, Philadelphia German Americans would travel to face St. Mary’s Celtic in Brooklyn on April 12. With Nemchik and McAlees both unavailable with injuries, Lutkefedder and Marty Regan would start.

Butz wrote in his April 13 Inquirer match report, “It was cup tie soccer from the opening whistle.” After five minutes of play, Celtic center forward Crilley nearly scored only to see his shot graze off the crossbar. Soon after, it was the Celtic defense that was clearing dangerous shots from German American left halfback Charlie Altemose. While Butz reported, “the soft under-surface bothered both teams,” the chances kept coming. Still, neither team could find that final decisive finish and at the half the score was 0-0.

The German Americans would create the first scoring opportunity of the second half but once again they were denied. Celtic continued to create chances of their own but they were visibly tiring in the grueling battle. Then, in 63rd minute, Richards gave the German Americans the 1-0 lead. Capitalizing on a missed clearance 18 yards from goal, “the Nanticoke blond raced in and drilled the ball three feet from the left upright,” easily beating the Celtic keeper. Butz reported, “The goal by the Quaker City boys took much from the tiring Celts.”

Richards would become the provider for the German Americans second goal. Receiving a throw-in near the six-yard mark, Bobby Nichol, who had been subbed in to replace Regan at inside right a minute before the first goal, played the ball to Richards, “and the Nanticoke lad turned it over his head” to center forward Lutkefedder who, coming to the end of a 15-yard run, headed past the Celtic keeper to Philadelphia the 2-0 win.

Game Two, April 19, 1936: Philadelphia German Americans 0-1 St. Mary’s Celtic

On April 19, Philadelphia German Americans hosted St. Mary’s Celtic at Tabor Field in what George Butz described in his Inquirer match report on April 20 as “the largest crowd ever to view a cup final in this city.” It would prove to be a bruising contest. Butz reported, “The game was unlike any other cup battle, much rough play working the players up to a fever pitch.” Indeed, after a scoreless first half, “The going got so torrid after the re-start that a fight took place between ‘Wild Bull’ Joe Martinelli, of the visiting booters, and Pete Petras, of the home club.”

Butz described,

Martinelli, the bustling centre halfback, started the trouble by planting a right on Pietras’ cheek. They tangled and when the players all jumped in to separate the spar boys, it was necessary for police to rush upon the scene.

Quiet and order was soon restored, although the gendarmes did have to remove a few boisterous Brooklyn rooters…

The Germans were battled by their foe throughout and the visitors were out to notch the Eastern Title at any means. As a result, the Celts’ backs hacked continually at the local forward liners. Due to the rugged play, it was remarkable that fisticuffs didn’t enter the game before Pietras and Martinelli tangled in the second half.

Neither Martinelli nor Pietras, who had been teammates on the 1934 US World Cup team, were removed from the game.

The skirmish appeared to fire up the Celtics and soon after, center forward Michaels scored the lone goal 15 minutes into the second half, emerging from a “wild scrimmage” in front of the Philadelphia goal to strike with a “twisting liner” from ten yards.

Despite the 1-0 loss, the German Americans were through to the two-legged National Challenge Cup final, winning the Eastern Division semifinal series 2-1 on aggregate. In the final they would face St. Louis Shamrocks. In league play, St. Mary’s Celtic would finish the ASL season in sixth place.

National Challenge Cup Final

Game One, April 26, 1936: St. Louis Shamrocks 2-2 Philadelphia German Americans

While Philadelphia German Americans would face the Shamrocks in St. Louis on April 26, in reality they were facing the same St. Louis team that, after losing the 1932 Cup final to New Bedford Whalers, had won the National Challenge Cup in 1933 and 1934 as Stix, Baer and Fuller, and again in 1935 as St. Louis Central Breweries. The team had provided four players to the 1934 US World Cup squad — William Lehman, Bill McLean, Werner Nilsen, and the Babe Ruth of American soccer, Billy Gonsalves.

In the first game of the final at Walsh Memorial Stadium, the 3,400 fans in attendance must have expected a victorious conclusion when, only eight minutes after the opening whistle, Shamrocks inside right Nilsen tapped in a corner kick from outside right Alex “Alec” McNab. But only two minutes later, Richards equalized for the German Americans. The April 27 Inquirer match report described, “Francis Ryan, outside left, took the ball down the field and sent a nice cross to Richards who beat the Shamrock goalie with his kick.” The first half would finish level at 1-1, the spectators being “treated to some fast and clean soccer,” although the Inquirer also reported, “Several outbreaks among the players” were prevented only due to some alert officiating from the referee.

The Shamrocks made several changes at the start of the second half, including bringing on Bert Patenaude, who had played for the German Americans only two years before. The changes saw St. Louis go on the offensive and for much of the half the Shamrocks had the ball in Philadelphia’s half. The Inquirer reported that “only great work by Goalie Denton kept the Rocks from scoring several more goals.”

In the 68th minute, St. Louis took the 2-1 lead when Nilsen scored his second goal of the game, assisted by Patenaude. Then, in the 89th minute, German Americans inside left William Fiedler raced down the field and sent home the tying goal. The Inquirer reported that, after the final whistle, “The fans gave him a great hand as he left the field.”

The second game of the final would be played a week later in Philadelphia.

Game Two, May 3, 1936: Philadelphia German Americans 3-0 St. Louis Shamrocks

It was a warm 80 degree day when Philadelphia German Americans hosted St. Louis Shamrocks in the deciding game of the 1936 National Challenge Cup on May 3 at their home field at Eighth Street and Tabor Road in front of some 5,000 spectators. The fans would not have long to wait for a goal. In the 25th minute, George Nemchik opened the scoring for the home team. George Butz reported in the May 4 edition of the Inquirer, “Fiedler fed the ball to Nemchik, who pivoted around a burly back and sent the leather neatly to the mark from a slight angle. It was a perfectly labeled six-yarder and unanticipated by the Shamrock goalie.”

In the 34th minute, Richards made it 2-0. “Getting the leather almost to the touch-line,” Butz reported, “Richards sent a high arching hook back into the strings. A little misunderstanding between [Shamrocks goalkeeper] Roderquiz and [left fullback] Davidson assisted the play. However, the ball was tabled and the goalie couldn’t hold it in a leaping catch.”

With the German American halfbacks frustrating Gonsalves, and McNab’s skillful dribbling coming to naught, the scoreline remained at 2-0 in favor of the German Americans at the end of the half. In the 69th minute, Nemchik scored again to make it 3-0, “just at a moment when the Shamrocks were pressing savagely for a score or two of their own.” Picking up the ball after a botched St. Louis kick at midfield, Fielder advanced toward the Shamrock’s goal. Butz described,

There was no stopping Fiedler as he weaved through the entire St. Louis back cordon. He finished his lengthy dribbling out in front of the Shamrock net. [Shamrocks right fullback] Lehman strived to get the ball out of danger, Nemchik tore in and got the leather. He made a fast pivot, pulled two backs out of his path and sent a hard drive through the visiting goalie’s guard.

St. Louis continued to battle, with Gonsalves and inside left Roe sending “hard socks” at the German Americans goal, But, Butz reported, “The agile Denton turned in another masterpiece in these tight places and he sprayed almost impossible shots from his station.”

While the Shamrocks began to tire, Butz reported that “The Germans continued to fight like wildcats.”

After 90 minutes of play, Philadelphia German Americans were the 3-0 victors, winning the two game final by the total score of 5-2 to become the first amateur team, and the first team from the city of Philadelphia, to win the National Challenge Cup, known today as the US Open Cup.

Butz wrote, “It is true that Lady Luck smiled, yes — even beamed on the Germans several moments in the second half when the Irishmen were staging many last ditch presses. But, notwithstanding those few breaks that always go to the victorious team, the Germans played soulful soccer throughout and rightfully deserve the grand final victory.”

Butz reported that, for Elmer Schroeder, the German Americans triumph was “the realization of a 20-year dream of an amateur team mounting to the high pedestal of soccer in this country. He has always had the desire to pilot such a squad and the boys obliged him yesterday, adding to their pair of National amateur titles they gained several years ago.”

That evening, at their clubhouse near the field where they had become national champions, the German Americans held their 12th anniversary dinner. During the dinner, team captain Francis Ryan was presented with the Dewar Challenge Trophy by USFA president Joseph E. Barriskill. Butz wrote the dinner “was the scene of much festivity.”

After the the 1936 National Challenge Cup

Nine Philadelphia German American players were selected for the US team that, coached by Philadelphia German Americans trainer Francis Cavanaugh and managed by Elmer Schroeder, played in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin: Robert Denton, Fred Stoll, James Crockett, Peter Pietras, Charles Altemose, Francis Ryan, George Nemchik, William Fiedler, and Frank Lutkefedder. There the US was defeated 1-0 by Italy, the team that had defeated them 7-1 in Rome at the 1934 World Cup. In 1937, Schroeder managed the US team that played three games in Mexico as part of the Castillo Najera Cup. Schroeder brought with him George Nemchik and Sam McAllees, who was by then playing in Reading, Pa. In the 1937-38 ASL season, the German Americans finished top of the league’s American Division, falling to the Kearney Scots in the semifinals of the league championship playoffs.

In 1938, Schroeder retired as manager the German Americans and was replaced by Emil Schillinger. Under Schillinger, the team became a powerhouse in the ASL. In the 1938-39 season, the team finished second in the American Division before going on to lose the Championship to the Kearny Scots. In 1942, after the entrance of the US in the Second World War, the German Americans became the Philadelphia Americans. That same year, the team won its second ASL championship, ending the Kearny Scots five year run of ASL titles. Over the next ten years, Philadelphia Americans would claim four more ASL championships in 1944, 1947, 1948, and 1952. During that same span, Philadelphia Nationals, home to such American soccer legends as Walt Bahr and Benny McLaughlin, would win the league championship three times (1949, 1950, 1951), adding another league title in the 1952-53 season. Between them, the Americans and the Nationals won nine ASL champions between 1942 and 1953, forming a veritable Philadelphia soccer dynasty in the league.

Before the start of the 1953-54 season, the Philadelphia Americans were bought by a local tricking magnate and became the Uhrik Tuckers, winning the ASL championship in 1954 and 1955. To say Philadelphia teams dominated the ASL in 1940s and 1950s almost feels like an understatement.

The German Americans would not win another Open Cup championship, going as far as the semifinals of the 1939 edition of the tournament where they lost to eventual champions St. Mary’s Celtic, the team they had defeated to reach the 1936 final. In 1948, the team reached the Eastern Division semifinals as the Philadelphia Americans only to lose to Brookhattan. (According to Wikipedia, the team reached the semifinals again in 1952, but I have so far been unable to learn who they lost to.) As the Uhrik Truckers, the team again reached the semifinals in 1955.

In 1960, Philadelphia’s Ukrainian Nationals, who joined the ASL when they bought the Philadelphia Nationals franchise in 1959 and would go on to further Philadelphia’s dominance of the ASL with six more league championships, became the first area team to win the US Open Cup since the German American’s win in 1936. They would go on to lift the Dewar Challenge Trophy title three more times.

On Tuesday, Sept. 16 at 7:30 pm, the Philadelphia Union will host three-time champion Seattle Sounders in the 2014 US Open Cup final at PPL Park (the history of the Philly and the US Open Cup Final, our look at Philly and the first US Open Cup, US National Soccer Hall of Fame historian Roger Allaway’s look at the Ukrainian Nationals 1960 championship victory, and Philadelphia soccer historian Steve Holroyd’s look at the Ukrainian Nationals and their three other US Open Cup championships.

Thanks for a great article. Really enjoyed all the details. I have always been told that basketball Hall of Famer Earl Monroe spent his early childhood playing soccer in the streets/fields of Philly. I read that he played baseball and soccer up until he was about 14. There’s always been a connection between good basketball players being developed by playing the beautiful game. Just wondering if you’ve heard this about Monroe and whether it might be a topic to write about, if you haven’t already.

Best,

Lindsey

Lindsey, thank you for your kind comment — and please accept my apologies for not seeing it sooner. This certainly is a topic worth exploring (and with the offseason upon us in Philly, now I’ll have some time!). I’ll let you know if I come up with something.

great article thank you.. my grandfather James Crockett played on these teams..the photo’s you included i haven’t seen before which he is in both so many thanks