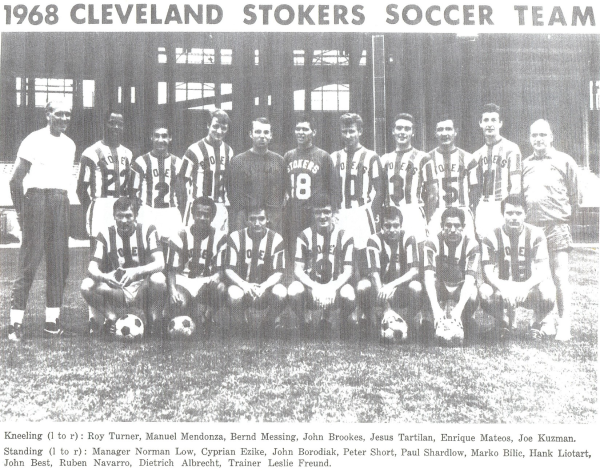

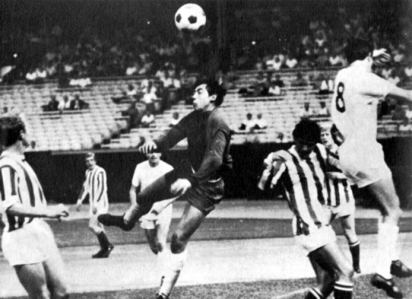

Photo: Stoke City’s Gordon Banks in goal for Cleveland Stokers. Courtesy of The Oatcake.

On Tuesday, the Philadelphia Union host English Premier League club Stoke City F.C. in a friendly at PPL Park. While not one of the more glamorous of English sides, having only returned to top flight football in 2008-09 after almost 30 years in the second and third divisions, it nevertheless has a deep and abiding history in England.

The Potters also have a bit of a history in America…and, in a roundabout way, a connection with Philadelphia soccer. But to examine this history, we’ll have to return to those bygone days of yesteryear…

Chaos and creation

The 1960s found professional sports booming in the United States. After about sixty years of sameness, major league baseball expanded by four teams in 1961-62, and by another four in 1969. The National Football League had a new rival in 1960—the American Football League—and merged with that league by the end of the decade. Similarly, the National Basketball Association gained a rival in 1967 (the American Basketball Association), and the National Hockey League doubled in size through expansion that same year.

No turn was left unturned in this sports boom, which is why 1966 found not one…not two…but three different ownership groups trying to form professional soccer leagues. Unlike other sports, however, soccer required sanctioning from a world-wide organizing body (FIFA) by way of the United States Soccer Federation. Ultimately, a group naming itself the North American Soccer League received the USSF’s stamp of approval, and was slated to being play in 1968.

This being America, however, the two spurned leagues did not take their rejections lying down. Instead, they merged with each other to form the National Professional Soccer League, and announced that—“outlaw” status or not—the league would begin play in 1967.

The NASL was not about to let a rival league have the American soccer landscape all to itself in 1967. Thus—after renaming itself the United Soccer Association (“USA,” get it?)—it announced that it, too, would hold a season in 1967.

However, it was not going to scramble for top quality players on such short notice. Instead, the USA would import entire teams to come and represent its franchise cities. Thus, teams like Wolverhamption of England and Aberdeen of Scotland found themselves representing Los Angeles Americans (renamed “Wolves” once Wolverhampton signed on) and Washington Whips, respectively.

The league tried to match clubs with the respective city’s dominant ethnic market. For example, the rather low-level Shamrock Rovers of Dublin represented the Boston Shamrocks.

The league tried to match clubs with the respective city’s dominant ethnic market. For example, the rather low-level Shamrock Rovers of Dublin represented the Boston Shamrocks.

The Cleveland franchise—owned by the Cleveland Indians baseball team—was not that picky, and just wanted a quality team, figuring that winning soccer would be sufficient to fill the cavernous Cleveland Municipal Stadium.

Here come the Stokers

Cleveland reached an agreement with Stoke City to come play the 1967 campaign. It was a pretty shrewd choice—Stoke City had just acquired goalkeeper Gordon Banks, netminder for England’s World Cup winning side from 1966, and already had established stars Peter Dobing, Roy Vernon, and George Eastham. Although a middle of the table side in England in 1966-67, Stoke would be one of the better sides in the USA.

Exhibiting little imagination, Cleveland’s owners promptly dubbed the club “Stokers,” and clad the team in Stoke City’s distinctive white with red stripes kits.

The Stokers acquitted themselves well in the thrown-together circuit, going undefeated in their first seven matches (4 wins, 3 draws). Coach Tony Waddington could rely on goals from Vernon and Dobing, while the goalkeeping trio of Banks (7 games, 1.56 GAA), Paul Shardlow (4 games) and John Farmer (3 games) allowed the second fewest goals in the circuit.

Cleveland only averaged about 6,500 per match, and never broke 10,000 for a game—resulting in a lot of rattling in the 78,000 seat home stadium.

The Stokers lost out on the Eastern Division title on the last game of the season, getting thrashed by Vancouver (represented by Sunderland) and allowing Washington to pip the crown. As a result, Cleveland missed out on the chance to play against Los Angeles in what has been described as the most exciting final in U.S. pro soccer history. Skeptical? See for yourself:

All told, the 1967 USA season was a rather crazy experience: so crazy, in fact, that Ian Thomson has recently written a book about it—Summer of ’67: Flower Power, Race Riots, Vietnam, and the Greatest Soccer Final Played on U.S. Soil.

Chaos and collapse

As one might expect, the effect of two competing soccer leagues in a market that, since the 1920s, had not really shown any interest in one was disastrous. However, both ownership groups were sure that the fault was the competition, and that one, unified league would attract fans in droves. The USA and NPSL merged, and the North American Soccer League name was recycled for the new circuit.

While the former NPSL teams had full rosters, the ex-USA teams had to start from scratch, a considerable disadvantage. Cleveland—now owned by future U.S. Senator Howard Metzenbaum, as the Indians had the sense to bail—came up with a quite practical solution to its problem.

You see, a few teams decided to take a pass on the merger, and one of them was the NPSL’s Philadelphia Spartans. Despite a strong second-place finish in its division (actually, the team was cheated out of a crown by the NPSL’s convoluted 6-points per win, 1-point per goal scored scoring system) and the fourth-highest average attendance in the league, owner Art Rooney (yes, that Art Rooney) decided he was not interested in subsidizing the team another year, and folded up shop.

Cleveland general manager Marsh Samuel recognized that acquiring the players of a de facto division winner would be a good start. He promptly snapped up 1967 NPSL MVP Ruben “The Hatchet” Navarro, Peter Short (4 goals), Roy Turner, John Borodiak, John Best, and Joe Kuzman. There was some semblance of consistency with the previous year’s side, as goalkeeper Paul Shardlow and defender Terry Conroy were acquired from Stoke.

The 1968 edition of the Stokers won the NASL’s Lakes Division with a 14-11-7 record, but were knocked out by the eventual champion Atlanta Chiefs in the first round of the playoffs. Cleveland could rely on a trio of forwards—Enrique Mateos (ex-Real Madrid), Amancio Cid, and Manuel Mendoza, who netted 16, 12, and 10 goals, respectively–and Shardlow was solid in net, appearing in all 32 games. Spartans alums Best and Navarro anchored the back line, and midfielder Turner contributed 4 markers. Thuggish, Danny Cruz-esque forward Short did not score, but contributed 6 assists.

The highlight of the year came on July 10, 1968, when the Stokers upset Santos of Brazil, led by Pelé, in a friendly.

While the quality of soccer in 1968 was outstanding, the crowds remained unimpressive—Cleveland averaged an awful 4,305 per match, pretty bad, and even with the also terrible league average. After the season, there was an epic collapse of franchises, with only five teams of 17 returning for 1969.

Cleveland, for its part, did not fold up shop at first. Instead—following the lead of several other franchises (Oakland Clippers, New York Generals, and Chicago Mustangs among them) unhappy with the austere fiscal restraints imposed on franchises by new NASL Commissioner Phil Woosnam—Cleveland initially went on “hiatus” in 1969. By November, however, the club had seen enough, and pulled the plug on the franchise.

Cleveland managed to connect with soccer fans; although major league outdoor soccer has never returned to the Forest City, it was home to a well-supported indoor franchise in the 1980s. If you can find it, James Alan Hofer’s Stoker Season: When Soccer Invaded The Neighborhood is a fun return to the era of Stokers soccer.

So there you have it: Stoke City, Cleveland, and Philadelphia. American pro soccer does indeed provide for some strange bedfellows.

Photo courtesy of NASLjerseys.com

Photo courtesy of NASLjerseys.com

RECENT COMMENTS