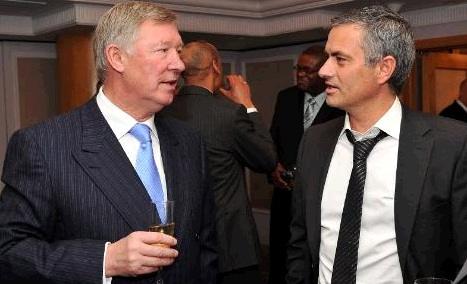

The presence of big business in soccer is rarely as clear as in a Champions League match-up between Manchester United and Real Madrid. When they meet in Spain on February 13, two of soccer’s greatest managers will lead two of the biggest soccer enterprises against each other.

A recent business-focused case study and older insider biography provide short and easy reads about how Alex Ferguson and Jose Mourinho manage not only highly talented rosters, but also highly valuable budgets.

Harvard Business Review is not often a source of soccer information, but it recently published a case study on Ferguson and his approach to management. The author, Anita Elberse, earned tenure as a Harvard Business School professor before turning 40 and previously published case studies on Real Madrid and Boca Juniors. The case study presents facts related to management of personnel and business issues without much analysis. Some of the tables with performance and financial information provide interesting comparisons of top clubs and managers.

In contrast to the factual presentation in the HBR case study, Mourinho’s friend, Luis Lourenco, has written a biography of the coach from an insider’s perspective. The close relationship between author and manager provides honest insight (as well as a possibly undercritical perspective).

As the Peter Nowak and Freddy Adu sagas linger in Philadelphia, we might also wonder how Ferguson or Mourinho would handle the same roster, locker room, budgetary, and contractual issues.

Management comments

In the HBR case study, Ferguson discussed his players, saying, “They have lived more sheltered lives, so they are much more fragile now than 25 years ago,” as well as himself by adding, “I was very aggressive all those years ago. I am passionate and want to win all the time. But today I’m more mellowed—age does that to you. And I can better handle those more fragile players now.”

Ferguson also described managing players, and particularly players who “have a bit of evil in them: One of my players has been sent off several times. He will do something if he gets the chance—even in training. Can I take it out of him? No. Would I want to take it out of him? No. If you take the aggression out of him, he is not himself. So you have to accept that there is a certain flaw that is counterbalanced by all the great things he can do.”

This comment provides fodder for speculation about which players he has in mind: Roy Keane, Paul Scholes, Wayne Rooney? For a manager known for strict discipline, Ferguson seems circumspect about “flaws” that often lead to needless fouls, injuries, and red and yellow cards that affect tactics and player selection. It is easier to sympathize with coaches like John Hackworth after reading about the compromises with volatile, selfish, or undisciplined players that a legendary manager with a massive budget must make.

Lourenco described Mourinho’s approach to disputes with both players and management at Benfica. In one instance, Egyptian Abdel Sattar Sabry aired his grievances through a translator to the Portuguese press, in violation of Mourinho’s stated policy that he and players always discuss issues in person rather than through the media. Mourinho retaliated by airing his issues with Sabry’s talent and benching the midfielder. Mourinho later reflected on that decision with the same type of understanding that Ferguson expressed for his players with “a bit of evil in them.” Mourinho later learned that Sabry’s translator had been significantly extending his statements when “translating” for the press, and he acknowledged that Sabry had been put in a very difficult situation by playing abroad where he did not speak the language, a common issue that must arise in most big clubs around the world.

When it came to team cohesion, however, Mourinho was unapologetic about his decision to take on management and possibly see the exit from Benfica. When the team arrived at its hotel for any away game, Mourinho discovered that the club had booked rooms for players in two separate sections. Favored players were given better rooms in a section of the hotel where the directors would stay. Mourinho moved all of the players into the better section, requiring the directors to move and occupy less favorable rooms. Benfica won the match and the league, but the team subsequently stayed in a low-budget hotel, and Mourinho was replaced.

A point of contrasting management styles arises in setting rosters and announcing starters for the next game. Both coaches decide the starting lineup five days in advance, but Ferguson announces it to the team two hours before game time while Mourinho announces it days ahead. This issue was an infamous source of tension when Bruce Arena managed the US men’s national team and seems to sporadically arise when players feel the strain of high-level competition and media.

Career statistics

The exhibits attached to the end of Elberse’s case study place Ferguson’s and United’s statistics in context with current revenue and historic performances. Of United’s three Champions League and 33 total European and domestic titles all-time, Ferguson was the manager for two of the Champions League and 27 of United’s overall titles. In comparison, Jose Mourinho has managed Benfica, Porto, Chelsea, Inter Milan, and Madrid to two Champions League and 14 overall titles.

There is also a presentation of estimated brand value and revenue of soccer clubs. United is the only club valued above $2 billion and is one of only five clubs, including Madrid, valued above $1 billion. Only Madrid and Barcelona drew more than $450 million in 2012, while United posted $367 million in 2012 revenues.

Elberse also provides the longest tenures of European managers (exhibit as of August 2011). In terms of endurance, Ferguson is unrivaled with 25 years of service. Arsene Wenger (Arsenal) and David Jeffrey (Linfield), with 15 years each, are next on the list. Guy Roux is reported as holding the record with 39 years at Auxerre. Mourinho has held head coaching positions for 11 years.

Ferguson and Elberse discuss some lessons that Ferguson has learned about how to survive at big clubs. Ferguson has incredibly spent almost his entire managing career at the same club. He notes that he fell out of favor with his first club president, and has conscientiously ingratiated himself with management since then.

Whether Mourinho has failed to learn these lessons, or simply prefers new scenery and challenges, he has not spent more than a few years at any one club. He fell out of favor at Benfica and Chelsea, and is now rumored to have issues at Madrid which he might leave in favor of Paris St. Germaine or succession of Ferguson at United.

The performance and tenure statistics show that Ferguson has won 1.12 titles per year and Mourinho has won 1.27 titles per year. The case study also includes an interesting comparison of managerial tenures in European countries, which reveals that coaches in England enjoy some of the longest tenures in Europe with a low proportion of firings during the first year and a high proportion of tenures lasting longer than three years.

Although Elberse’s case study does not express any judgment of Ferguson, her presentation of statistics and his commentary give fans and managers information to appreciate and learn from Ferguson’s decisions. Mourinho’s biography also provides interesting background on a great manager, and in very different style than the HBR case study. I appreciate that both the case study and the biography are brief, but they provide insights to appreciate this year’s Champions League matchup from the perspective of two great managers.

RECENT COMMENTS