The season opening win in 2011 was not a pretty one. Danny Califf’s 5th minute header sucked the ambition from the Union and forced Houston to push forward impatiently, throwing wave after wave against Philadelphia’s rocks.

When you want to hold a lead for 85 minutes on the road, a conservative 4-3-3 seems like a darn good option. Luckily, that’s what the Union happened to have on the field. Brian Carroll, Stefani Miglioranzi and Kyle Nakazawa rarely ventured out of the middle third of the pitch, an unadventurous yet pragmatic plan after taking an early lead.

Portland tactics

Against Portland, the Union opened with four attacking players on the pitch, yet their approach was largely the same. Gomez and Carroll sat deep to distribute and prevent counterattacks, leaving the attacking to FreddyMarfanTinez and Lionard Pajoy.

As a result, the stats for 2012’s opening match look very similar to those of 2011. Only the scoreline changed for the worse.

| 2012 | 2011 | |||

| Union | Portland | Union | Houston | |

| Attempts on goal | 5 | 17 | 7 | 19 |

| Shots on goal | 2 | 8 | 4 | 3 |

| Corner kicks | 1 | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| Crosses | 11 | 23 | 4 | 17 |

| Total Passes | 341 | 416 | 296 | 532 |

| Passing Accuracy | 70% | 74% | 72% | 79% |

| Possession | 44.40% | 55.60% | 35.10% | 64.90% |

The worrying theme of these stats is that the Union were no better offensively when they were even with or chasing Portland compared to when they were defending a road lead at Houston. And remember: This is with an entirely new attack (the only similarity being approximately 30 MwangaMinutes in each game).

Why couldn’t the Union’s rebuilt offense challenge Portland’s back four? It’s not like Jack Jewsbury and Diego Chara are known for their ability to protect their defense, so it’s more likely that the Union were unable to create space for their playmakers because those playmakers were not on the same page.

Freddy Adu is not going to streak behind defenses, but Michael Farfan and Josue Martinez? At least one of them should be moving enough to create space and confusion in the Portland defense. Then it is just a matter of getting the ball to the right players in the right positions.

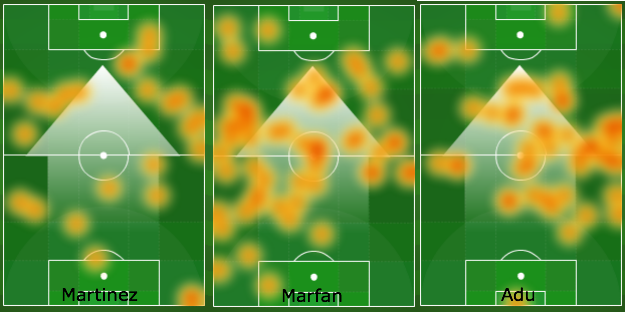

There are two ways to look at the heat maps above. Perhaps they show a mobile, fluid midfield in which the creative players find each other all over the pitch. If you watched Monday night’s match, however, you know that we are looking at three players who did not know where to be or how to get involved. Adu showed the most maturity, seeking out a comfort zone on the right from which to operate. Unfortunately, the Union’s central midfielders were so deep that Adu’s gap was in the same area that Sheanon Williams looked to take up when the ball was worked out of the back.

Martinez, on the other hand, never looked comfortable. He was cognizant of Porfirio Lopez’s desire to get forward but unable to find any holes in the Portland defense where he could get involved. Some of Martinez’s troubles fall on Michael Farfan’s shoulders. Clearly seeking to make his mark as a distributor, Marfan forgot what made him such a dynamic rookie: Isolating himself and beating defenders. As Marfan struggled to link Gomez and Carroll to the rest of the midfield, the rest of the offense showed no initiative to look for a back door into the Portland half.

Gavilan’s game

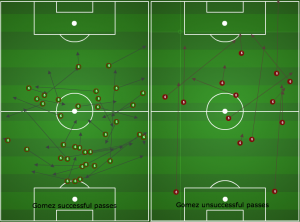

Have a look at Gabriel Gomez’s passing charts:

To start the offense, Gomez dropped deep between Califf and Valdes, allowing the outside backs to push high. This accounts for many of Gomez’s passes from deep in his own half. The troubling aspect of these passing charts is that Gomez has two completed passes in the final third of the field. This becomes an issue when you look at the Union wingbacks. Pushing the backs high up the pitch is done (successfully) for two major reasons: 1) The Barcelona Argument, and 2) The Mourinho Argument.

The Barcelona argument

Barcelona pushes the backs high up the pitch to get more players involved in the offense. It’s just one twist in their plot to create space for Iniesta and Xavi deep in the opponent’s half by drawing midfielders out of position. You will not see a Barcelona player cross the ball unless Messi is sitting on Fabregas’s shoulders unmarked inside the six or as a last resort.

The Mourinho argument

Mourinho (and, really, Chelsea and Inter Milan ever since he was there) uses the backs in a more traditional sense: They get up the field to create mismatches and overload one side of the pitch to the point where the defense either overcommits or leaves someone open for an easy cross. A perfect example of The Mourinho Argument came on Chelsea’s first goal against Napoli yesterday. Pushing Ashley Cole forward overloaded the left side of the pitch, so when Ramires stepped wide, he was given ample time to find Drogba with a stinging cross.

Why they work

In both arguments for pushing the backs high, the main goal is not to use them as outlets for the defense. They make it easier to link the backs to the central midfielders, yes, but the real danger comes when they establish themselves high up the pitch. Then the whole team moves forward and, importantly, the central midfielders either drift wide to overload a wing or crowd the top of the box to make it difficult for defenders to track runners.

Neither of these arguments supports the manner in which the Union used their outside backs on Monday. Returning to Gomez’s passing chart, it is worrisome to see such a talented passer uninvolved more than eight yards beyond the midfield stripe. Gomez’s mobility and skill (as well as his crossing ability) would be maximized by involving him in the wing play high up the pitch. This would also create the numbers Sheanon Williams needs to free himself up for darting runs into the box from the wing, runs that are rarely marked in MLS and have become a big part of the LA Galaxy’s successful formula.

What’s next for Philly

Monday night’s match showed that while the Union players may understand what is being asked of them, they may not grasp the “why.” This isn’t because they are dumb; Freddy Adu and Michael Farfan are intelligent attackers who are capable of finding space or a nifty pass. The goal of any soccer strategy is, of course, goals. It’s one thing to tell your players where to be and where to pass the ball, but it’s another to make them recognize what that achieves two, three, four passes down the line.

Danny Califf’s early goal let the Union off the hook in 2011: An argument can be made that offensive strategies largely go out the window when you are defending a lead on the road. But in 2010 and again in 2012, the team has been a tactical mess in their opener. Whether it is how they prepare in preseason or poor communication from the coaching staff, something needs to be addressed.

This team needs to recognize that the loss to Portland was not due to a lack of talent or heart, but a lack of identity. And now, they have to find that identity.

That’s nice analysis, and as positive as you all have been of late. At least you feel like we can fix it…probably should mention though that the two teams that use these outside back pressing systems most effectively are also the best two teams in the world. For some reason I have trouble comparing Lopez and Williams to Dani Alves and Abidal. Perhaps the point is the one you all made in a previous article and that is play a more traditional 4-4-2 and let the players use their skills.

That’s a good point, Blake. But it’s also the case that a system can make an outside back look like a superstar. Just look at the rise and fall of Maicon during Mourinho’s stay at Inter. There’s also the Tottenham conundrum, where the team seems to be most effective when they play with traditional wingers who push the ball fast and hard, yet recently they’ve been trying to get the backs involved. When Walker/Assou-Ekotto get upfield, the team often seems less threatening (though Walker on his game is a scary sight).

VERY nice breakdown