Even in a World Cup year, it can be difficult to explain to non-soccer-loving Americans just how powerful a force the game of soccer is in the world. Soccer has helped to start wars. It has also given vent to the emotions of wars long over. And it has stopped wars, if only for a day.

Soccer can be the spark that ignites the flames of war

In an already existing atmosphere of heightened political tensions over the borders between El Salvador and Honduras, the qualifying matches for the 1970 World Cup between those two countries led to La guerra del fútbol or “The Football War.” After 100 hours of combat some 3,000 soldiers and civilians were dead and hundreds of thousands of civilians had been displaced. After the war, because each country had won the home leg of their qualifiers, a play-off had to be played, which El Salvador won. They didn’t make it out of the group stages of the World Cup in Mexico and some four decades later the demarcation of the new borders between the two countries has yet to be formalized.

Soccer can be the symbol that finally turns the page on a long ended war

After Holland beat Germany in the semi finals of Euro 1988, an estimated 70% of the population poured into the streets for the largest spontaneous celebration in Holland since its liberation by the Allies in World War Two. Sure, it was revenge for the defeats suffered by Holland against West Germany in the 1974 World Cup Final and in the first round of the 1980 European Championship. But the bitter rivalry between “the Cheeseheads” and “the Krauts” has it’s foundation in World War Two. In 1988, for one night, Holland settled the score.

Soccer can also stop a war, if only for a day

The First World War began in August, 1914. Troops on both sides went to war believing that it would all be over by Christmas. By December, tens of thousand were killed and wounded, trenches had been dug across the length of the Western Front, and peace was four long years away.

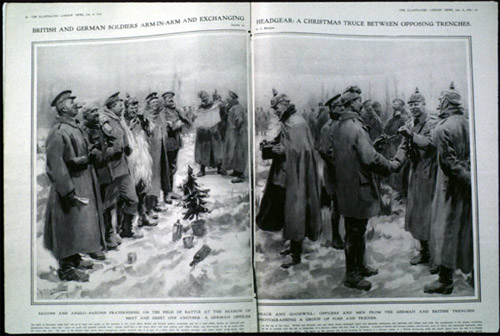

Some of the trenches were close enough to one another that voices could be heard from those opposite. On Christmas Eve, 1914, German troops began to decorate their trenches with candles and to sing Christmas songs. British troops answered with Christmas songs of their own. Soon, small parties of troops began to enter No Man’s Land to exchange Christmas greetings and presents with those who, only hours before, they had been expected to kill on sight.

Many British soldiers had enlisted in the army with groups of friends to form units that were consciously identified with soccer such as the Chelsea “Die Hards” of the 17th Middlesex Regiment and the “2nd Footballers” of the 21st Middlesex Regiment. On the German side, the 133rd Saxon Regiment had a proud pre-war football record.

Officers and soldiers found themselves talking soccer with their enemies. Soon impromptu games were being played with “goals made from caps and frozen sentries, balls from jam-tin bombs and ‘Ole Bill’ woolly mufflers.” In one sector, a British colonel reported that, though the Germans wanted to play a match, the Scots Guards facing them across No Man’s Land were unable to supply a ball.

In Frélinghien, France, British soldiers from Royal Welch Fusiliers faced German soldiers of the Saxon Infantry and the Prussian Jäger. After exchanging two barrels of beer and a Christmas pudding, a match was played. Some 94 years later, soldiers from the descendant units of those which had met during the Christmas Truce played another soccer match where the first had been played before the unveiling of a memorial to commemorate the event.

Such impromptu cease fires were viewed as anathema to military discipline and commanders on both sides were quick to forbid their re-occurrence under threat of swift punishment. Even still, French and German troops managed a Christmas truce in 1915.

While some revisionist historians have questioned whether soccer matches took place during the Christmas Truce, the evidence that they did can be found in the scores of letters, notes, diaries and oral histories of soldiers from both sides. One soldier, Alfred Anderson, described the “eerie sound of silence” as the fighting stopped and soldiers emerged from their trenches to exchange Christmas greetings. Anderson was the sole surviving soldier to have experienced the Christmas Truce when he died at the age of 109 in 2005.

So, in this holiday season, should you have a conversation with some friends or family who “just don’t get this soccer thing,” you can tell them about the games in No Man’s Land, about how soccer stopped a war, if only for a few hours, on the cold, muddy, shell-marked fields of the Western Front.

A version of this article originally appeared on December 25, 2009.

this is paul’s version http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OLkABxWn8wU

I HATE THIS