This concludes the two-part series on the Philadelphia Phillies short-lived soccer team of 1894. You can read the first part here.

With the first ALPF season fast approaching, the Philadelphia Phillies played a picked eleven at the Philadelphia Ball Park on October 1, winning 3–0, although it is unclear who exactly picked the eleven. They then beat Philadelphia Wanderers 3–1 the next day.

Such promising beginnings came to a halt with the start of the season. Facing the New York Giants in the opening game on October 6, the Phillies lost 5–0. A second game played against the Giants on October 9 was lost by the Phillies, 5–2

The American Association Philadelphia team met the Newark team at Stenton, Wayne Junction on Saturday, October 13, the same day and time that the Phillies played the Washington Senators at the Philadelphia Base Ball Park.

I have not been able to find attendance figures for either of these games but it seems likely that the Phillies would have drawn fewer spectators than the American Association Philadelphia team: the possible spectacle of watching a few professional baseball players playing soccer aside, soccer fans would probably have preferred to watch known players who had so well represented their city on the All-Philadelphia team in past amateur matches.

Still, the Inquirer was optimistic about the prospects of the ALPF. Though soccer had been played in Philadelphia for years, the Inquirer reported on October 14, 1984 that the game had “been patronized mostly by men who played on the other side of the Atlantic;” with the formation of the ALPF “it looks as if the game would soon become popular with the masses.”

There is sufficient rough play to add zest to the sport and the kicking and the “head play” combined with sprinting are features which cannot help but interest. Most of the players are Englishmen and Irishmen and some have been imported. As soon as they become better known to the public much more interest will be added to the game.

Whether the Phillies would in fact become popular with the masses remained to be seen.

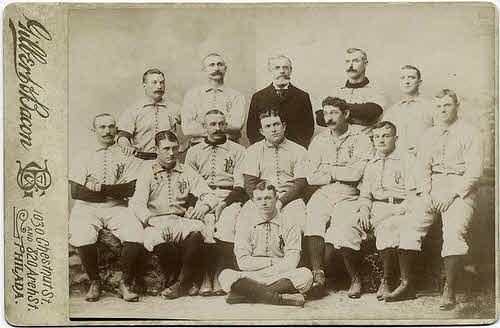

The Phillies won their first league match on October 15th, beating the Washington Senators 4–0, having lost to them in their first encounter 2–1. Among the Phillies on the field that day were at least two members of the baseball team, Charlie Reilly and future Hall of Famer Sam Thompson. Known as “Princeton Charlie” after his place of birth, it is possible that as a child Reilly had watched or played the rough and tumble soccer-style football which had before the advent of American gridiron football been popular at Princeton, which had been an early center of collegiate soccer. If so, that might help to explain why he was “ejected from the field for wrestling.” The game that day was also notable for the apparent use of substitutions, a practice that would not become generally allowed in soccer until the second half of the Twentieth Century. In the event, Reilly seems to be the only Phillies baseball player to have played in every Phillies soccer game.

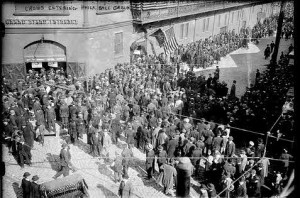

The Phillies were beaten by Boston, 5–2 in front of four hundred spectators on October 20th, a very poor showing for a Saturday match when one considers that a match in Baltimore against Washington drew four thousand spectators only two days before. As David Wangerin writes in Soccer in a Football World, “Baseball champions in 1894, the Orioles had taken the trouble of hiring a bona fide soccer coach, AW Stewart, who doubled as the team’s goalkeeper.” Only five hundred people showed up in Baltimore on October 23rd to watch the Orioles trounce the Phillies 6–1, in what proved to be the last game of the ALPF.

After all of the hope and hype for the prospects of America’s first professional soccer league, the ALPF had collapsed after only 18 days. While the ALPF cited the “late period at which this association got underway and the difficulty of avoiding conflict with the regular college football games” as the reasons for the cessation of the league, poor planning, bad scheduling of games, a growing scandal about the use of foreign players in Baltimore (Stewart had imported players from Manchester City and Sheffield United), and the distraction caused by rumors about the formation of a rival professional baseball league are more likely causes.

With the exception of some very large crowds in Baltimore, attendance had been dismal throughout the league. The largest crowd for a Phillies game was reported as “525” for the Philadelphia vs. Boston game, although the Philadelphia Inquirer match report for that game puts the attendance at “about four hundred.”

The Phillies weren’t making money on the road either: the Inquirer reported that the Phillies had received $9.22 for two games in Brooklyn and $60 for two games in Washington, ridiculously low figures when one considers that the entrance fee for matches was 25 cents, half of what it cost at the time to see a professional baseball game.

The ALPF said the league would “reorganize on somewhat different lines” for the 1895 season and the Baltimore and Washington teams seemed particularly keen to continue but the league was finished. Despite the 2–7 record of the Phillies in league play, the abysmal attendance figures and the general evidence that he would best stick to baseball and leave soccer to those with some experience with the game, Irwin said he planned to “organize a strong team of local players to play at Philadelphia Ball Park on Saturdays.” At least he now seemed aware of the potential for soccer’s working class fan base to come to see a soccer game if only most games were scheduled for a time when they could attend. In the end, the ALPF and Irwin’s plans faded into history.

Meanwhile, the other professional Philadelphia team continued to play. On October 27th they met Pennsylvania Association Football Union champions Philadelphia Athletic at Stenton, Wayne Junction. “After a great deal of dickering and badgering,” Irwin took up a challenge offered by Clement Beecroft, manager of the American Association Philadelphia team, to play for $100 a side and the title of champions of Philadelphia. Unfortunately, I can find no record of the match or even confirm that it happened. No doubt Beecroft’s Philadelphia team would have destroyed Irwin’s Phillies. On October 11 the Philadelphia team defeated a Paterson, New Jersey team 7–2 at Wayne Junction, continuing their dominance of all opposition.

On November 24th, the Philadelphia team had a role in helping to restart college soccer when they played the newly organized Princeton team at Stenton, Wayne Junction. Princeton lost 7–1. (I diverge from standard history here as most sources suggest that it was the Philadelphia Phillies who played Princeton in this historic match. However, I believe that, along with the fact that the match was played at Stenton rather than Philadelphia Park, a close examination of the Philadelphia team roster for this game as published in the Philadelphia Inquirer match report of November 25, 1894 confirms that the side was made up of players from the American Association team organized by Beecroft. The Inquirer game report for the match refers to the team as “the crack Philadelphia eleven,” hardly the term for the Phillies team, whose APFL record was 2-7-0. I am continuing to research this and welcome information about possible sources.)

Named after a local brewer, the Philadelphia team became the John A. Manz team in 1895 and proved to be unstoppable against local opposition. In 1897 Manz (who are frequently and erroneously referred to as “Manx” in many sources) won the American Cup.

Philadelphia’s baseball grounds would continue to be used for soccer in the off season. The Philadelphia Ball Park, eventually renamed the Baker Bowl, would be the home grounds of several Philadelphia soccer teams in the American Soccer League (ASL). As Wangerin notes, it was but one of several “decaying major league baseball parks” used by teams in the ASL. Perhaps most notable team to play at the Baker Bowl was the Philadelphia Field Club, an incarnation of Bethlehem Steel FC, the most dominant soccer team in America in the first half of the Twentieth Century. The Baker Bowl was torn down in 1950.

The Phillies left the Baker Bowl in 1938 to share Shibe Park with the Athletics until they left town in 1954. Shibe Park was eventually renamed Connie Mack Stadium and it was the home of the Phillies until Veterans Stadium opened in 1971. Veterans Stadium would be the home of the NASL champion Philadelphia Atoms and later the Philadelphia Fury. If you drive around the city today, pickup and league soccer games in the outfields of the city’s baseball and softball fields are a familiar sight.

RECENT COMMENTS