Cover photo: Paul Rudderow

Eric Ayuk has taken a strange path to Major League Soccer, from his home in Cameroon to Thailand’s obscure lower divisions and finally to Philadelphia Union.

On paper, the talented teenager’s arrival in America to play for Major League Soccer came via a small, lower division Cameroonian club known as Rainbow FC of Bamenda.

In reality, it came through the broader efforts of the sports management agency that owns Rainbow FC, whose critics claim the club is little more than a nominal means of circumventing FIFA’s ban on third party ownership of player’s rights.

“Ayuk never played for Rainbow,” said Portuguese agent Paulo Teixeira, who is representing at least one Cameroonian youth club in a potential claim against Rainbow and MLS. “Neither him, nor any of the players that have moved to MLS. Rainbow are a regional club which has no weight whatsoever in the [Cameroonian] Championship.”

Buried below Cameroonian professional soccer’s top two tiers in the Northwest Regional League, Rainbow FC is owned by Rainbow Sports Investments (RSI), a sports management agency that also represents more than 40 African players as agents and has facilitated a number of player transfers to MLS, USL PRO and European leagues. The man behind Rainbow is Kingsley Pungong, a Wharton School-trained businessman who previously worked as an agent for the Wasserman Media Group, where he reportedly oversaw the agency’s African soccer strategy.

The most well-known of the transfers Pungong and his holdings have brokered with MLS have stood out primarily for the unusual circumstances that accompanied them.

- Ambroise Oyongo: The Cameroonian international left back joined the New York Red Bulls on loan in 2014. After New York traded him to Montreal, he refused to report to the club for weeks as claims arose from Rainbow and Cameroon that he was an amateur — not professional — player and therefore could not be traded.

- Charles Eloundou: Colorado acquired the young Cameroonian attacker in 2013 on loan with an option to purchase his rights. He didn’t report and play his first match for the Rapids until more than a year later, as a confusing dispute ensued over his rights.

Ayuk’s arrival is the latest MLS acquisition brokered by Pungong and his Rainbow portfolio to come with questions attached.

- Ayuk’s contract provided by Teixeira — dated nearly four months before his signing announcement from the Union — shows it to be a loan to MLS with an option to purchase at year’s end for $200,000. The Union confirmed this to be correct on Wednesday.

- Ayuk’s acquisition prompted at least one of his former youth clubs in Cameroon to seek training compensation funds from MLS, Philadelphia Union and/or Rainbow.

- The transactions of Ayuk and other Rainbow players have prompted claims that Pungong and Rainbow are exploiting a loophole in FIFA’s ban on third party ownership of players’ rights.

Pungong did not respond to emails and did not answer his telephone when called by The Philly Soccer Page.

MLS and Philadelphia Union declined to comment on record for this story or make Ayuk available for interview. A U.S. Soccer spokesman did not respond to an email for comment.

Claims of training compensation

Cameroonian clubs All Sport, Canon Sportif, AS Fortuna have sought training compensation through Teixeira for Ayuk and New York Red Bulls forward Anatole Abang, another Rainbow FC player who signed with MLS in December. Ayuk played for All Sport, while Abang played for the other two clubs.

FIFA regulations require training compensation be paid to a player’s youth clubs:

Training compensation shall be paid to a player’s training club(s): (1) when a player signs his first contract as a professional and (2) each time a professional is transferred until the end of the season of his 23rd birthday. The obligation to pay training compensation arises whether the transfer takes place during or at the end of the player’s contract.

The purpose behind this rule is to prevent wealthy clubs from raiding small clubs of their most talented players without fair compensation.

Rainbow has denied the validity of the claims brought forth by Teixeira. Pungong recently began discussions with AS Fortuna on the condition that Teixeira was excluded from the discussion, according to Teixeira. An agreement appears to have been reached there, because MLS now has a waiver from AS Fortuna. The other claims remain pending, according to Teixeira. He indicated the Union and MLS were on the hook based on FIFA regulations, but he said his clients were more concerned with receiving fair compensation than with who paid it.

MLS generally refuses to pay training compensation, as the recent case of DeAndre Yedlin has demonstrated. MLS and U.S. Soccer have disputed the legality of FIFA’s requirement in the United States. Additionally, MLS reasons that, with most American youth players paying to play for youth clubs, these clubs have theoretically already been paid for their services rendered and therefore need no further compensation.

Foreign clubs usually have no such pay-to-pay arrangements with youth players, which means a different situation may arise in foreign players’ cases, like that of these Cameroonian youth clubs.

Regardless, MLS includes language in new player contracts stipulating that the selling or loaning club waives the right to training compensation fees. This appears to be the case with Ayuk, according to a segment of his loan contract provided by Teixeira. However, with players like Ayuk sometimes playing for multiple youth clubs, the situation arises in which some of a player’s prior youth clubs are not part of the contract under which he joins his first professional club. The contract waiver may mean little to them because they are not the party who signed it, and they still pursue the claim, as was the case for the aforementioned former clubs of Ayuk and Abang.

The question of third party ownership

Beyond the training compensation claim lies the larger question of whether Rainbow is effectively engaging in third party ownership, in which any third party other than a team or free agent player holds the respective player’s transfer rights. FIFA’s ban on the practice went into effect in May.

Critics of third party ownership compare it to trading in human chattel, and it has been a disputed topic ever since Carlos Tevez’s controversial move to Manchester United in 2007. However, third party ownership has its proponents, most notably in South America, where they say outside investors are often required to help finance players’ moves for economically unsound clubs.

Brazilian sports management agency Traffic Sports effectively pioneered the model that Pungong and RSI appear to be using in Cameroon. Traffic invested in the rights of South American players for years, becoming power brokers in the European transfer market in the process. Subsequently, Traffic invested in actual club ownership.

- In 2005, Traffic founded Sao Paolo club Desportivo Brasil, which currently plays in Brazil’s fourth tier and has been used as a talent factory for selling young players to larger clubs. Traffic sold the club to a Chinese consortium last year.

- Traffic later acquired Portuguese first division club Estoril.

- Traffic has also owned several teams in the second tier North American Soccer League, most of which have since been sold.

- Traffic also helped launch the NASL as an independent league in 2009. Its top American executive, Aaron Davidson, was the league’s board chairman until he and other Traffic executives were indicted on corruption charges in the U.S. Department of Justice’s high-profile investigation into corruption at FIFA.

To be clear, RSI has not faced criminal allegations of the kind that led to the Traffic indictments, and there are surely differences between their operations.

But the similarities between their models are clear.

One one hand, RSI and Pungong acquire ownership of player rights under the umbrella of Rainbow FC and subsequently profit from their sales to bigger clubs. Separately, RSI represents players as sports management representatives outside the umbrella of Rainbow FC and presumably collects agent, marketing and/or other fees for that work.

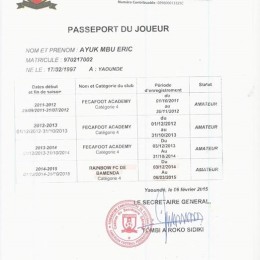

Question arise, however, when a youth player like Ayuk is sent by the Rainbow/RSI umbrella to play for teams in Thailand while still an amateur. FIFA regulations only allow for loans of professional players, and Ayuk was an amateur while playing in Thailand, according to a copy of his Cameroonian player registration provided by Teixeira. Additionally, FIFA regulations also forbid the transfers of players under age 18, with three exceptions:

- The player lives within 50 km of the new club’s border;

- The transfers occur within the European Union;

- The player’s parents move to the country for non-soccer reasons.

None appear to apply to Ayuk, who turned 18 this year.

“As said, the basic idea is good, [but] the way Rainbow worked it out is a disaster,” Teixeira said via email. “I guess this happened because they ignored or disregard the international regulation on transfers. But [I have] never seen any company doing it this way. You have for instance Traffic, the one involved with US DoJ. They run clubs which really invest (Desportivo Brasil or Estoril in Portugal for instance) in education. Rainbow is just a pass-by.”

The parallels of Ayuk and Oyongo

It remains unclear whether Ayuk and other Rainbow-linked players ever actually played for Rainbow FC’s senior team. He reportedly joined the Rainbow umbrella in 2011. By 2013, RSI had facilitated the teenager’s move to Buriram United in Thailand, where RSI maintains an office and has sent several players, including Frank Acheampong, who was subsequently sold to Anderlecht for 1 million euros. After arriving in Thailand, Ayuk apparently played for two semipro teams there, one of which — Surin City FC — has a history of acquiring players on loan from Buriram.

Ayuk did not register as a professional until Dec. 1, 2014, 15 days prior to the date on his loan contract with MLS. This established the legal paperwork necessary to secure his loan to MLS and the potential $200,000 transfer fee from MLS at year’s end. (Abang’s registration with Rainbow FC is also dated Dec. 1, shortly before his move to MLS.)

Ayuk’s situation is similar in some ways to the case of Ambroise Oyongo, albeit with a distinct twist detailed by the individual who reportedly was Oyongo’s agent, Nicolas Onissé. LastWordonSports.com reported in February:

At the start of 2015 it was revealed that New York Red Bulls had not officially signed Oyongo, and that he was on loan from Cameroonian club Coton Sport FC. That was untrue, as Oyongo had no contract with them at the time. Oyongo was actually on loan from FC Rainbow, who it was revealed later was an amateur club who could not legally sign professional contracts.

“He never played for Rainbow, he just signed with them,” explains Onissé. Oyongo was told that if he didn’t sign with Rainbow he wouldn’t get a deal with MLS. This contract was never registered with FECA FOOT or the Cameroon soccer league, they didn’t know about it until recently.

The response from Rainbow

The Philly Soccer Page sent Rainbow chief executive Kingsley Pungong multiple emails over the last two weeks and called him in Cameroon but never received a response. Momchil Durlev, Pungong’s co-founder of Rainbow World Group, the apparent parent company of RSI, referred inquiries about the company’s soccer portfolio to Pungong and confirmed Pungong’s email address and phone number were correct.

Rainbow has, however, refuted Teixeira’s claims through Alex Morfaw, the vice president of Rainbow FC of Bamenda, in a statement published in French on the Cameroon Football Federation’s website. In the statement, Morfaw claimed the copy of Ayuk’s MLS loan contract provided by Teixeira is a fake. He said Rainbow FC is not responsible for paying any related training compensation claims.

Further, Morfaw said Rainbow created its development and transfer model as a means for income in situations where it has no significant television or sponsorship income. He stressed that the contracts with the players are consensual and that Rainbow has broken no rules with its methodology, including the ban on third party ownership. Previously, another representative of Rainbow FC denied claims that the club had engaged in third party ownership with Oyongo, according to OnceAMetro.com.

Questions remain

While Ayuk’s situation may be a local case study, several Rainbow products are now playing in MLS and elsewhere, with more likely on the way. So the remaining questions regarding Ayuk’s path to MLS may be relevant for others.

- How did Ayuk play for teams in Thailand while still attached in some way to Rainbow? Was he on loan from Rainbow FC?

- If so, how is that possible when he was an amateur player and FIFA regulations allow only professional players to be loaned?

- If he was not on loan, was he then an amateur player choosing to play for the Thai club while RSI represented him as an agent, only for RSI to later represent him as a team via Rainbow FC?

- Will future training compensation claims accompany these other players?

- Will Rainbow’s model drive similar initiatives elsewhere in African soccer?

- And what really happened behind the scenes in each of the other unusual cases related to Rainbow FC?

The list of questions could go on. The answers are not yet clear.

Nice work, Dan. Fascinating stuff…

yes, agreed, to the degree that I understand it.

Somehow I think this ends with the Union winning millions of dollars from a prince from Keyna as soon as they reply with their bank account information!

Oh, come on. Everybody knows that’s a scam – even Sak. Instead, they’re looking at helping a businessman from Nigeria. Millions, man! Millions!

HAHA… well done both of you.

.

This was a great read. More good stuff from PSP. This is the best site going.

Excellent read. May be the best article I’ve read on PSP. And that’s not a slight, the work here is excellent.

.

I think its going to be tough for these clubs in Africa to get compensation, particularly when USSF doesn’t recognize training compensation and there is a waiver clause in the contract. Easy way for MLS to go “not our problem” etc. Not saying its ethical, but it may not violate any laws… aside from the spirit of them

This is some serious journalism, Dan. Well done. My only request is for perhaps some extra background on the regulations and aspects of soccer business that are pertinent here — some of us love the game but have little sense of the (extremely arcane) business behind it.

I can add some background. What do you think was missing? I worried about bogging down the story with too much, which I may have done anyway.

No way. Definitely not too much info. Maybe I’m a geek like that. But I, for one, want to know as much as you have to offer. Great job. Thanks Dan, PSP. Where else would you get this kind of story?

Perhaps write the fully “backgrounded” story and post a link to it at the bottom of the general consumption article?

.

Alternatively, a general primer on soccer business practices? Perhaps two, if such a pattern actually fits the material, one a basic introduction and the second a more advanced elaboration. I would have to start at the basic level and then move on. Of course practice may very well vary significantly from continent to continent and business tradition to business tradition.

While I think it is a good article I would like to point out that the player registration looks very much photoshopped and/or written over to include Rainbow FC. You can see a clear distinct change in the texture and color of the background which makes me think things were changed. Whether when it was given for the article or before then I do not know and I don’t know the details of how this business side of things work. However this looked odd to me and would wonder how it changed things. Ultimately I would just hope if wouldn’t affect the Union from grabbing Ayuk full time for a long term contract this kid could be very good with some experience and has no fear which I like.

I continue to be blown away by the quality of coverage on this site. Bravo.