On June 9, 1916, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported, “Word was received in this city yesterday that all arrangements had been completed for an All-American soccer team to tour Sweden and Norway in July. The Sweden Football Association, through its secretary, C.L. Kornerup, has cabled a guarantee of $4000 to cover the expenses of the trip. This guarantee is now on deposit in a New York bank.”

US soccer was about to embark on its first international tour, right in the middle of the First World War.

How the tour came to be

On May 29, 1916, the third annual meeting of the United States Football Association, today known as the US Soccer Federation, was held at the Hotel Walton in Philadelphia, then located at the southeast corner of Broad and Locust Streets before it was demolished in 1966. Among the minutes of the meeting in the 1916-17 edition of the Spalding Guide are reports and recommendations from various committees. The assembled delegates approved the recommendation “that the Association take up and foster development of soccer football in the schools.” The report from the National Challenge Cup Competition Committee, known today as the US Open Cup and won only a few weeks earlier on May 6 of that year by Bethlehem Steel FC, noted that the total income to the USFA from the Cup competition that year was $1,955.21, about $40,600 in current dollars. From the Emergency Committee was this:

Sunday, March 12—Meeting of the Committee held in New Bedford, Mass. Communication from Cuba regarding international game was considered and a reply sent calling their attention to the fact that they were not affiliated with the F.I.F.A; also a letter from Sweden was given consideration. Secretary Cahill was ordered to reply to the latter communication.

The “letter from Sweden”—a neutral in the World War, as was the US at the time—contained an invitation for a US team to travel to Scandinavia for a tour and it did not come from out of the blue; Thomas Cahill had visited Sweden in 1912 to lobby for USFA’s recognition by FIFA, which was meeting there in conjunction with the 1912 Stockholm Olympics. Later, Cahill had sent Kornerup, secretary of the Swedish Football Association, a copy of the 1915-16 Spalding Guide, of which he was the editor. Hence the “letter from Sweden.”

Cahill wasted no time in replying to Kornerup’s invitation. The report on the Scandinavian tour in the 1916-17 Spalding Guide says, “He likewise took up the subject with Chairman Douglas Stewart of the National and International Games Committee of the United States Football Association and other men prominent in the affairs of that body.” At the May 29 annual meeting—during which Stewart, long a fixture in the Philadelphia soccer scene as a player, coach and administrator, would be confirmed as the Second Vice President of the association—the proposition of a Scandinavian tour was put before the USFA representatives to “ask formal approval and consent for the enterprise, which were readily obtained.”

The main obstacle in making the trip happen had been how to pay for it: the USFA simply did not have the money. Cables from both parties had crisscrossed the Atlantic since March to rectify the problem. Finally, when the USFA met in Philadelphia, “the Swedish proposition to guarantee $4,000 for such a tour” could be read to the delegates. In the end, the tour wouldn’t cost the USFA a cent—the Swedes picked up the entire tab.

Now the problem was this: which team should represent the US?

Bethlehem FC says “no” to the tour

The obvious answer seems to have been that the champions of the country. In the spring of 1916, the champions of the Country were none other than Bethlehem Steel FC, recent winners of both the USFA’s National Challenge Cup and the American Football Association’s American Cup tournaments. An article headlined “Soccer Champs Will Not Tour Sweden” in the June 11 edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer seems to support the notion that this was certainly what the Swedish FA had in mind. Citing events on June 10, the article reports,

The Bethlehem Steel Company decided today that it would not take the chance of sending its champion soccer team across the ocean to Norway and Sweden in these war time [sic] to play a series of games with elevens in those countries. Therefore, the Sweden Football Association was cabled that its invitation would not be accepted, although that organization had posted $4000 in this country to defray expenses.

The company’s concern was understandable. Little more than a year before, the Lusitania had been sunk off of the Irish coast by a German U-Boat. Some 1,200 passengers perished in the sinking.

Selecting the All-American team

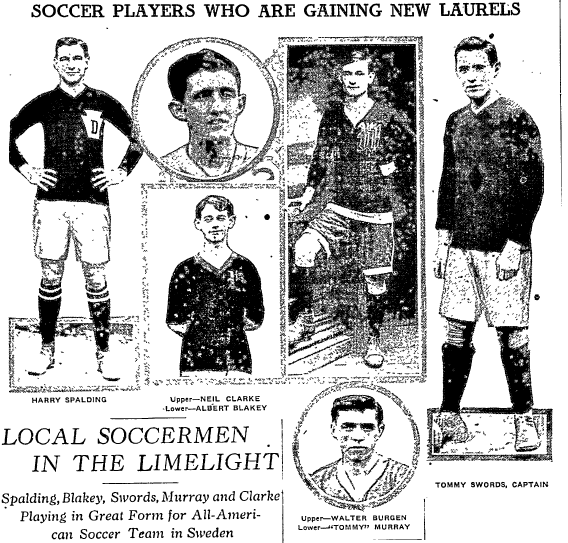

The 1916-17 Spalding Guide says that, with no time to arrange for tryouts, team selection was thus left to “the knowledge and experience of the members of the National and International Games Committee,” which included people like Philadelphia’s Douglas Stewart. In the end, five area players would be selected for the team. On July 23, the Inquirer reported, “Three local soccer players are included in the All-American lineup which sails for Sweden next Wednesday.” They were C.H. “Dick” Spalding, left fullback with Tacony’s Disston AA team, co-champions with Bethlehem of the city’s American League; left halfback Albert Blakey of the city’s Allied American League champions, Putnam FC; and Walter Burgin, inside left for Philadelphia Wanderers, also in the Allied League. The Inquirer report notes,

All the three players were taught their soccer in this city. Spaulding [sic] graduating from the [Lighthouse] Boys’ Club and who is considered by experts the best full-back in the country. Blakey and Bergin [sic], although not having yet the opportunity of playing in fast company, are players above the average ability, and if supported properly they should uphold the fair name of this city even when pitted against the best that Sweden can produce.

The local connections continued with Thomas Murray and Neil G. Clarke, right halfback and center halfback for Bethlehem Steel, and the only two players of the 14 selected who had not been born in the US. Also with the team was Thomas Swords, a Fall River native who had played for Philadelphia Hibernian between 1910 and 1912 and who would be elected captain of the team on the voyage to Scandinavia, and James Ford of Ryerson FC in Kearny, NJ, who had scored the winning goal for Bethlehem Steel in their 3–1 win over Brooklyn Celtic in the 1914-15 National Challenge Cup final. Both would play in every game. Cahill joined the team as manager.

An Associated Press article that appeared in newspapers around the country at the time of the team’s departure from Hoboken on July 26 aboard the Frederick VIII of the Scandinavia-America line provided a glimpse of the American game plan. “The Scandinavian footballers are noted for their brawn,” it said.”To offset this, the national and international games committee of the U.S.F.A. has constructed a picked team whose strong point is speed.”

Despite the wide distribution of the AP article—it appeared in newspapers as dispersed as Ohio, South Dakota, California, Florida and Colorado—David Wangerin writes in Soccer in a Football World that the tour was met with “profound apathy and skepticism from the sporting public.” The account of the tour in the 1916-17 Spalding Guide says, “So dubious were American followers of soccer generally as to the outcome of the enterprise, that hardly a handful of enthusiasts gathered at the pier to bid the team good-bye and wish it luck. Many telegrams of Godspeed, however, were received by the departing tourists.” When facing touring English teams such as the Pilgrims and the Corinthians in the past decade, American teams had, with rare exception, been soundly trounced. The All-American’s prospects against Swedish and Norwegian sides that had had the benefit of regular international matches with before the start of the First World War gave few American soccer observers cause for optimism.

By coincidence, J.S. Edstrom, Vice-President of the Swedish Olympic Committee, was on board ship. In addition to “advising them of the standard of soccer in Sweden,” Edstrom informed the players “of the frame of mind of the people of Scandinavia with reference to the Great War and urged them to observe the strictest neutrality in their conduct and speech.”

In Scandinavia

After a 12-day voyage, the All-Americans arrived in Christiana (present day Oslo) on August 7. The voyage had gone without incident, the trip filled with a daily routine of exercise and sport that included “deck walking…calisthenics, body exercises, rope skipping, boxing and hand tennis.” The team arrived in Stockholm on August 8 to be greeted with much interest, helped no doubt by the fact that the Dagens Nyheter newspaper had under-written the tour.

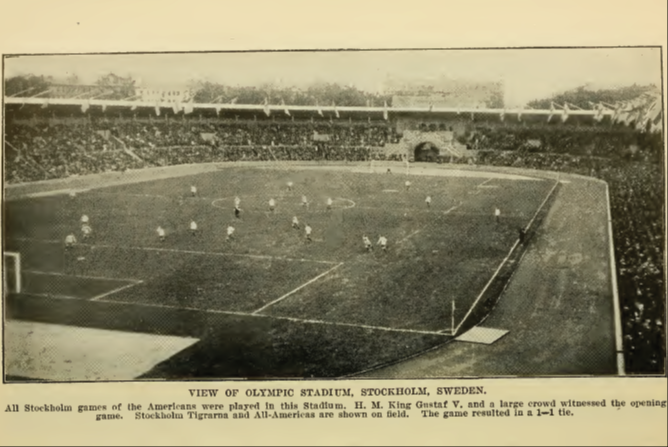

After a week filled with series of receptions and banquets, the All-Americans faced their first opponent on August 15 at Stockholm’s Olympic Stadium. In front of nearly 20,000 spectators, the All-Americans played and All-Stockholm side (referred to as Stockholm Tigrama, or Stockholm “Tigers,” in some accounts) to a 1–1 tie with Spalding, Murray, Clarke and Blakey all starting. John “Rabbit” Hemingsley of the Newark Scottish-Americans scored the All-American goal.

A report in the Inquirer on August 17 (which is prefaced with the phrase “Delayed by Censor”) says, “Spalding, of Philadelphia, playing at left back, served the American team with conspicuous effectiveness, repeatedly earning the aplause [sic] of the crowd, which was well versed in the fine points of the game…Murray and Clarke, of the Bethlehems, were of valuable assistance in the half back division.”

At halftime, Sweden’s King Gustav V “sent for Mr. Cahill and in a brief address thanked the U.S.F.A., through him, for sending the team over, complimented the association on its enterprise and daring in sending abroad an athletic team during war time.”

The team next faced the Swedish Federation All-Sweden team on August 20, again at Stockholm’s Olympic Stadium. The Spalding Guide describes the game as being “considered the biggest and most important of the entire series”— it was the first international match against another national team in the three-year-old USFA’s short history. Playing in “a light mist” in front of 17,000 spectators, the All-American’s won 3–2. Spalding, Murray and Clark all started (Clarence Smith of North Jersey team Babcock & Wilcox started in place of Blakey). The Spalding Guide, which listed Burgin as being a linesman for the game, concluded, “It was the match of the competition and the victory was a great triumph for American soccer.”

Wangerin writes of the victory, “None of Sweden’s 37 previous matches seem to have prepared them for the Americans’ all-consuming desire for victory, manifested in such unsporting tactics as stalling to take a throw-in, playing defensively to protect a lead and even shouting for the ball…The US’s high-tempo, ball-chasing style seemed outmoded to a country which had grown accustomed to a less frenzied passing game.”

“Local Soccermen in the Limelight”

“Local Soccermen in the Limelight”

The good showing by the All-Americans in their first two games surprised many American soccer fans back in the States, and the Inquirer was no exception. An article from August 27 describes, “Even the most enthusiastic were somewhat leery at the time when the team was announced that it would not be able to hold its own in any of the matches, but now that the tourists have proved their worth, it would not be surprising if they get an even break of the five-game series that was arranged prior to the team leaving this country.”

The article shows obvious pride in the good play of the players with local connections:

One of the most pleasing features about the opening contest with Stockholm was the splendid playing of the Philadelphia lads…When one takes into consideration that such players as Spalding, Swords and Blakey have not had the opportunity in receiving any expert schooling in the rudiments of the game, the same as quite a number of players that have come here from England and Scotland, their prowess is all the more noteworthy, for all of the soccer they have gotten into their think tanks has been picked up on the various city lots either by participating in a practice match or else in witnessing some of the players who came from England a few years ago who were considered clever exponents of the game.

Singling out great names from Philadelphia’s soccer past such as Tommy Greene, Horace Pike, Albert Hickling, Pete Wilson, James Dawes, David Gould and Andrew Brown, the article concludes, “These players…paved the way for the present-day standard of soccer, for practically the rising element who are now regulars on the various teams received valuable aid from witnessing the former cracks play at Sixth and Clearfield streets, Third street and Lehigh avenue, Cliggett’s Park and other historic grounds in the days of the zenith of the Pennsylvania League, which has since gone out of existence.”

Who scored the first US goal in a full international?

Various sources—an account of the game in the August 21 edition of the Inquirer, Wangerin, Tony Cirino’s U.S. Soccer vs the World, the account in the online American Soccer History Archives (which very closely follows Cirino’s account)—indicate that Swords scored the first US goal in a full international. Interestingly, however, Swords is not listed as a goalscorer in that game in the 1916-17 Spalding Guide. Philadelphia’s Spalding is listed as a goalscorer for that game and that game alone.

The Wangerin account of the game does not list the scorers of the second and third US goals but the Inquirer article, Cirino and ASHA agree that Charles Ellis (Brooklyn Celtic) and Harry Cooper (New York Continentals) scored the second and third goal. The goalscorers for the win over the All-Sweden team are listed alphabetically in the Spalding Guide, which suggests the possibility that Spalding may have scored the first US goal in a full international. Cirino, who does not link Spalding’s goal to a specific match in his account of the tour, nevertheless writes, “The most spectacular goal [of the tour] was the one by Spalding, a fullback from Disston A.A. of Philadelphia, who scored after dribbling down the entire length of the field.”

So, did former Philadelphia Hibernian player Thomas Swords score the first US goal in a full international or did Philadelphia born and Disston star Dick Spalding? I have no idea, but Spalding’s goal seems to have been spectacular. If anyone out there knows Swedish and has access to an archive of Swedish newspapers or the archive of the Swedish FA, please get in touch.

First loss and crowd violence

The All-Americans suffered their first loss of the tour in their next game on August 24, going down 3–0 to a team composed of all-stars from the AIK and Djurgardens teams. Spalding, Murray, Clarke and Blakey all started. In a speech at a banquet after the game, “Mr. Cahill frankly admitted that for the first time during their visit the All-Americas had been outplayed.” Cahill went on to say that the team “had grown stale,” that by now the All-American’s faced three fresh teams in less the ten days. In the spirit of good sportsmanship, the AIK/Djurgardens combination team offered the visitors a return match, to be played as the final game of the tour. But first, the Americans would travel to Gothenburg to face Orgryte Idrottssallskopf on August 27.

Spalding was rested for this game with Murray, Clarke and Blakey starting in a 2–1 victory for the All-Americans. The winning goal came in the closing moments of the match and the Gothenburg spectators were not pleased with the loss. As they left the pitch, the American players were attacked—the Spalding Guide notes that this had previously happened in Gothenburg to the visiting Manchester City and Glasgow Rangers teams—and their vehicles were stoned as the team tried to make its way back to its hotel. Wangerin quotes a newspaper account about what happened when one assailant tried to make off with Cahill’s “prized American flag.”

Calling to the chauffeur to stop, Cahill leaped out and, pursuing the vandal, delivered some well-aimed blows with his cane, He was making good headway toward the complete annihilation of his opponent when policemen with drawn swords interfered and drove Cahill back. The crowd gathered again and the Americans were lucky in making their escape.

Upon learning of the incident, the Spalding Guide reports that King Gustav was “vexed…and ordered a special commission to investigate and punish the offenders.” After a week off, the American team returned to Gothenburg en route to their second full international against the All-Norway team in Christiania, present day Oslo. During a luncheon in their honor, “The visiting players were given medals, and in speeches made by the mayor of the city and other prominent men, regrets for the unpleasantness of the day were expressed feelingly.”

Wangerin suggests that some of the anger directed at the Americans could have been connected to their style of play. “In defeating Orgryte 2–1 the All-Americans were roundly criticized for playing in the style of beginners, or belonging to a more primitive era.” But Wangerin also points to Gothenburg sports writer Carl Linde to illustrate that some Swedish observers saw something to praise—albeit with condescension— in the Americans style of play. Linde witnessed a “new way of playing” in which the All-Americans “form a very dangerous team, mainly through their primitive brutality, through their speed and through their will to win at all costs.” Another writer quoted by Wangerin says the the Americans’ work rate made the Swedish side look like they were engaged in “exercise for older gents.”

Finishing on the ascendant

In Oslo, the All-Americans played to a 1–1 draw against the All-Norway team, with Spalding, Murray, and Clarke starting. The draw was actually something of an accomplishment, despite coming against a team that had failed to record a win in 19 international matches. In the age of no substitutions, the Americans lost inside left Matt Diedrichsen (Innisfalls FC) to injury in the 35th minute. In the second half, Smith left the game and the Americans finished with nine men.

The team returned to Stockholm for the final game of the tour, the grudge match against the AIK/Djurgardens combination team on September 6. Spalding and Clarke started, with Burgin getting his first start of the tour. The All-Americans finished the game as 2–1 winners.

Legacy

Departing from Oslo on September 8, the All-American’s arrived in Hoboken aboard the steamship Oscar II on September 19 with a 3–1–2 record, 1–0–1 in full internationals. It was an admirable conclusion for a team that so many American soccer observers had given little chance for success. Ellis and team trainer Harry Davenport had been offered contracts and stayed behind.

The 1916-17 Spalding guide contains a letter written by Kornerup to the USFA after the tour in which he wrote, “We have seen the fresh, breezy rushes of your men and learned to admire them and their tactics on the football field, and to regard them as our friends, before and after the fray.” Cahill was honest in his appraisal of the Americans’ performance. “We were outclassed by the Swedish players on straight football. It was American grit, pluck and endurance that won. No great football stars were members of our team, but we had the pluckiest aggregation ever banded together.”

When Bethlehem Steel became the first US club to tour abroad in 1919, also in Scandinavia, four players from the 1916 All-American team were on the roster: goalkeeper George Tintle, center forward John Heminsley, fullback James Robertson and Albert Blakey.

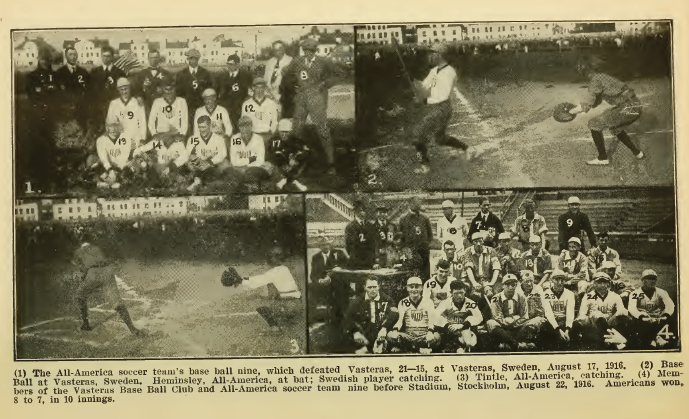

Among the equipment the All-Americans had brought with them for the tour was baseball gear. The team played two games against the Vasteras Baseball Club during the tour, winning by the combined score of 29–22. At the end of the third inning in the the first game, the contest was so one sided that “the players were redistributed so as to give Vasteras several of the Americans.” King Gustav was apparently quite taken with the game. Spalding would go on to play for Bethlehem Steel, ending his soccer career in 1925 with Philadelphia’s Fleischer Yarn. In 1927, Spalding signed with the Philadelphia Phillies as a outfielder before finishing his MLB playing career with the Washington Senators in 1928. In 1934, he returned to the Phillies as first base coach.

A US national team would not play a full international again until the 1924 Olympics in Paris. The US wouldn’t play in Sweden again until 1995.

I see you share interesting content here, you can earn some additional money, your website has big potential, for the monetizing method, just

search in google – K2 advices how to monetize a website

Hi,

the first goal by american player in a international football match was scored by Spalding.

I have the correct information having the official book of Swedish Federation.

http://barcalcio.net/100-anni-fa-la-prima-partita-della-nazionale-usa/