Photo by Chris Gibbons, Logo courtesy of the Philadelphia Union

(Takes about 12 minutes to read)

The most important book in the history of investing is Benjamin Graham’s “The Intelligent Investor.”

The nearly hundred year old text is Warren Buffett’s bible and its updated copies are a mainstay on Zoom meeting backgrounds in the world of finance. Despite it’s girth, the tome’s lessons for investment management can be summarized in five bullet points:

- Analyze for the long term

- Protect yourself from losses

- Don’t go for crazy profits

- Never trust Mr. Markets

- Stick to a formula by which you make all investments

This outline is prudent for putting money to work. It is also a useful guide for understanding how the Union do so.

Analyze for the long term

Buying and selling stocks is not investing, it’s speculating.

Speculators hope something good will happen over short periods of time, investors know something good will happen over long periods of time. The Union’s strategy is similar, and for good reason.

Buying expensive new players every year is impossible for almost every club in the world. That Barcelona and Inter Milan are both “on the verge of bankruptcy” suggests no one is immune. Building academies that produce quality players every year is perhaps even more difficult. Barca and Ajax are some of the most obvious names who do this well, but even they go through long dry spells from that water source.

The problem?

Most owners are stuck trying to win games without as much money or as much local talent as they want.

Union ownership is made up of a group of (mostly) real estate investors, or people who only invest for very long periods of time. The head of this group is famous for the 99 year leases his company offers. Bilbo Baggins was eleventy-one years old in the first Lord of the Rings book, but it’s hard to be a lot more long-term focused as a human than looking a century ahead.

Thus, it’s no surprise the Union are built in a similar vein: from the ground up, with a decidedly long-term focus. No one is buying the penthouse apartment, but instead are building entire apartment complexes to sell to Europeans, over and over again.

Protect yourself from losses

This might seem like an obvious statement, but for most speculators it’s not.

The proof?

Almost every single person who day-trades (also known as speculators, gamblers, or the greater fools) loses money and about 85% of professionals whose job it is to be good at this kind of thing do worse than having done nothing over the long run. Much of the same is true in Major League Soccer: the best teams in the league aren’t the ones who regularly chase shiny objects and hope for the best, they’re the ones who build thoughtful rosters that may not be great at every position, but have a hard time being bad as a group (see Columbus, Seattle, Philadelphia, and Portland).

For example, FC Cincinnati had a total roster budget of about $9 million dollars in 2019. That was an average spend for the league, but Cincy were terrible on the field. Logic says they should have upgraded at every position.

Instead, this offseason they paid $13 million for one player: Brenner. They chased a shiny object. Though he earned a penalty and nabbed a goal in the team’s opener, so far in two matches the other players on his side have faced 43 shots and been outscored 7 – 2 (for context, 2019 was Andre Blake’s worst year, one in which he faced about 150 shots over more than 30 matches).

Cincinnati still might make the playoffs this year, this is MLS after all.

But since the team’s ownership paid $13 million for a player worth about half that much in the open market, even if they do they’re in the hole. They’d have been better off signing thirteen one million-dollar players than one thirteen million dollar play, which would have followed this section’s rule and answers the argument about fighting a horse-sized duck or a gaggle of duck-sized horses.

In investing and Major League Soccer, the little horses win.

Don’t go for crazy profits

Speculating on stocks might be fun, but actual investing should be boring.

The news is full of sexy new companies to buy and the chance each one has to make the reader millions. Pyramid schemes like Dogecoin and the GameStop short squeeze only quicken the boil. The fact is most sexy new companies fail: for every Tesla there are two Pets.coms or eToys, almost no one makes money guessing which will be which. The worst part of this conundrum is the ones who do guess right believe they have skill when they are actually just lucky.

Overpriced Designated Players are the MLS equivalent of fence-swinging stock speculation: big signings signal to fans that something is happening, and do so in such a way that the argument against the amorphous “trying to win” is rendered moot. Just like stock speculation, they’re conversation fodder too.

It’s championship or bust! They’re doubling down! They’re going all in! They’re raising the stakes!

Or, all the things someone might say about a gambler when he or she has no other options left.

The obvious problem?

On the list of all-time league transfers, the only players whose names appear and who also lifted a trophy are the ones with more than one teammate on the list and a well-respected manager. By spreading out one’s risk between several investments with upside potential and having a grownup in the room to manage them, the chance of hitting a home run goes down but the likelihood of not striking out goes up (and stays up over time).

This is how the Union are built, with risk spread across the team in roughly even amounts and last year’s coach of the year in charge.

Never trust Mr. Markets

In the spring of 1720, Sir Isaac Newton owned shares in the South Sea Company, the hottest stock in England. Sensing that the market was getting out of hand, the great physicist muttered that he ‘could calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, but not the madness of the people.’

Newton dumped his South Sea shares, pocketing 100% profit totaling £7,000.

But just months later, swept up in the wild enthusiasm of the market, Newton jumped back in at a much higher price-and lost £20,000 (or about £4,500,000 in today’s money).

For the rest of his life, he forbade anyone to speak the words “South Sea” in his presence. – Benjamin Graham, The Intelligent Investor

Markets are “emotional, euphoric, moody, irrational, and subjective,” among other things. Uncovering the reasons for “Why” they move the way they do is a fool’s errand. In fact, “Why” might be the hardest variable to quantify in all of investing (not to mention economics, psychology, and more), and yet there is an entire industry built around doing so: looking at charts and matching the movement of lines like palm readers.

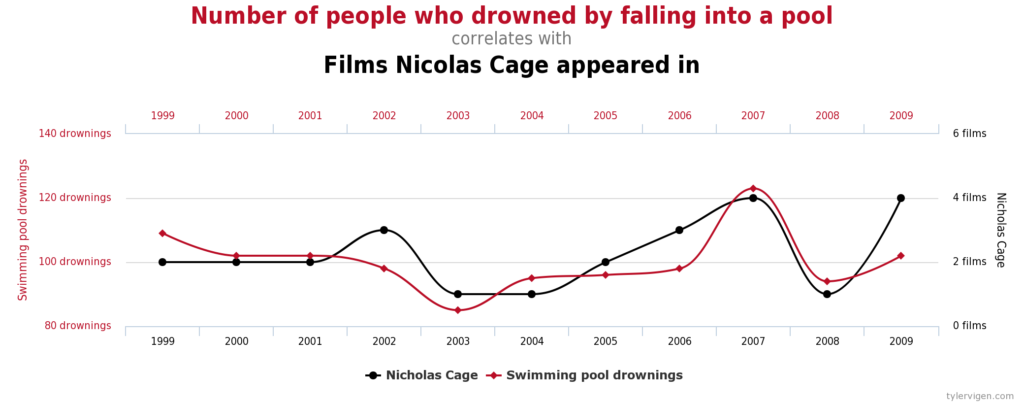

The problem? Lines lie.

(Author’s note: obviously the joke about the chart above is, “But do they?”)

Mr. Markets has sports corollary and readers of this website might not like finding out who that person is… because Mr. Markets is Fans. Fans, short for “fanatics,” are fairly reliably “emotional, euphoric, moody, irrational, and subjective,” among other things.

Philadelphia legend Buddy Ryan once said, “If you start listening to the fans, you’ll be sitting up there with them.”

Right he was.

Author’s note: This section comes with a major caveat given the Super League debacle of last week. When fans identify and demonize the upper echelon’s of the game’s greed, that is not Mr. Markets behavior but as rational as can be.

Stick to a formula by which you make all investments

If an investor is committed to thoroughly researched, boring and unsexy investments that meet his or her long-term needs, he or she has one crucial tenet left for being successful over the course of that long time period:

DON’T MESS IT UP.

There is an entire scientific field of study dedicated to the foolish things we all do when making decisions, and specifically how those foolish things hurt us when it comes to investing our money. The last thing an investor should do when his or her prudent strategy is working, or especially when it’s not for a temporary period of time (see Mr. Markets section), is do something rash. The old adage of “buy low, sell high” is almost exactly the opposite of what most speculators do: they panic when things get bad, sell low, and then wait for things to get better before getting back in, buy high, only to have the floor fall out from beneath them.

Rinse, repeat, run out of money.

For the Union, this means sticking with their plan even in years when they have profits from the sale of their investments (Brendan Aaronson and Mark McKenzie) that they could splash on the Brenners of the world. They shouldn’t do that because buying Brenners is speculator behavior, while taking thoughtfully earned profits and reinvesting them thoughtfully is what investors do. Replication of a good strategy increases the likelihood of long-term success.

After all, one Brenner is worth seven Jamiro Monteiros, ten Alejandro Bedoyas, or some unknown large number of eventual first-team homegrowns.

Summary

The thing about a good investment strategy is some days, some weeks, some months, and even some years, it’s going to look like a failure.

The proof? The market is only up a fraction more often than it is down on a daily basis. Saturday night against Miami was one of those down days: the Union couldn’t hit the target and Miami’s high-priced talent scored goals, sparking an upset victory.

The other side of this deceiving market coin flip lies in the data that savvy long term investments pay off: the market has only ever had one ten-year period in which returns weren’t positive.

Ever.

The Intelligent Investor says the lesson from a down day in the market, or from a match like the one the Union lost over the weekend, should be this one: as long as the overall strategy is sound, close the book and move on.

Tonight the Union will do just that.

Author’s note: This is not a piece vilifying the industries of investing or financial advice. A good investment or financial advisor will help with the outlined process and the diligence required to stick to it. However, he or she will not have a magic wand, crystal ball, or any other unique money-making strategy.

Really good article. Made some great points. Enjoyed the read and always enjoy the podcast as well

Thank you kindly.

This is an excellent piece with a good message that I hope gets across to the people that jumped back onto the Union cliff edge after 1 bad result.

Magic. Excellent content. Thank you.

.

I appreciate the shout out for The Intelligent Investor and how it relates to UnionLand. Personally I’d prefer a young team out there tonight but that’s probably a wrong choice by me.

.

In other news, I wonder what the advent of Cryptomarkets…. will do for Warren Buffett’s Bible. Might need a re-write.

One thing that struck me is MLS’ roster rules somewhat run against the protect yourself from losses argument with how DPs exist. Considering you can only really spend money on three players, it can easily lead to the kind of situation you see in Cincinnati where the bulk of the signings is geared towards getting a few players at premium positions. Even clubs who generally spread the money around their roster will concentrate some salary in one or two really important players (for instance, Nico Lodeiro with the Sounders makes about 2.5 million a year and was signed on a six million transfer fee). Philadelphia really are somewhat of an exception here.

Should they actually sign Daniel Gazdag of Budapest Honveld, he will be expensive by Union standards.

.

He is not out of contract soon, and his roster value according to Transfermarkt is $1.1 million.

.

Tanner’s leverage is empty stadia impacting revenue for clubs in leagues that have lesser TV contracts.

Transfer Market also listed the Metz to Philadelphia signing of Jamiro Monteiro as a $1.98 million signing. So a Daniel Gazdag signing for 1.1 to 2 million would be in that range.

Obviously that’s some big money, but that’s less than the biggest transfers of many other clubs.

Loved the piece, Chris. Well argued, clear.

.

In re Newtown’s south Sea Bubble, in 1636-7 the Dutch went crazy over tulips, Tulip Mania in English. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tulip_mania

.

19th-century United States economic history has a bubble and a crash roughly every 20 years or so, particularly after Jackson destroyed the 2nd Bank of the United States. The pattern does not stop until The Federal Reserve System is created in 1913 during the Wilson Administration, and even it could not stop the Bank Panic of 1933.