Just imagine…

A United States soccer league playing a winter/spring schedule…having a contract with a major television station featuring matches of the week…regularly filling stadiums to capacity…and featuring promotion and relegation.

A dream come true for certain segments of the today’s soccer community. Yet, during the Eisenhower Era and into the 1960s, it was more than just a dream for soccer fans in the Windy City. It was very much a reality.

So, even though it had nothing to do with the City of Brotherly Love, let’s go back and take a look at a time when indoor soccer was king in Chicago.

The National Soccer League

For some reason, historians have been very kind to the (second) American Soccer League, and will wax euphoric about the St. Louis leagues when discussing American soccer in the years between the original American Soccer League and the return of major league soccer in 1967 with what would eventually become the North American Soccer League.

Strangely overlooked is Chicago’s National Soccer League. Formed in 1908-09, the circuit featured many of the best players and teams in the Midwest. Understandably in the shadow of the ASL throughout the 1920s, the NSL came into its own in the years without a single dominant professional league.

By 1938, an NSL team—Chicago Sparta—won the U.S. Open Cup, and repeated as co-champions in 1940. In addition, NSL teams made up most of the circuit in the first attempt to bring back “major” professional soccer in the United States, the North American Soccer Football League of 1946 and 1947.

Those teams had returned to the NSL by 1948, and the league itself was a healthy entity with 42 senior, 12 junior, and five juvenile teams within its jurisdiction. The senior group was bracketed into five divisions: Major; Major Reserve; First Division, North; First Division, South; and First Division, Reserve. At the end of each season, the winners of the North and South branches of the First Division would be promoted to the Major Division, while the two bottom finishers in the Major Division were relegated.

As the sheer number of teams would suggest, the NSL was no mere local league, confined to the Chicago city limits. Rather, the territory covered by the senior divisions extended over a 150 mile area, and included teams from four states: Wisconsin, Iowa, Indiana, and Illinois. Represented cities included Milwaukee, Davenport, Fort Wayne, Rockford, Coal City, and Joliet.

And, of course, a number of teams from Chicago: Vikings, Sparta, Hansa, Schwaben, Slovaks, Swedish-Americans, Hakoah Center, and Necaxa, among others. Windy City clubs tended to monopolize the Major Division, as well as the Peel Cup, an Illinois state championship dating from 1908-09.

Alas, as the names of those clubs would suggest, the NSL was a circuit very much dominated by ethnic social clubs, even at a time when the ASL would (albeit temporarily) dissuade its clubs from adopting such names.

The NSL did deviate from other soccer leagues of the era in one significant way: seeing the chaos the weather caused to the ASL’s schedule on an annual basis, the Chicago league opened its season in April and concluded November.

While this summer schedule allowed teams to complete their fixture lists in relatively temperate conditions, it did leave players idle during a time of year when virtually every other soccer club in the country—including those in the NSL’s primary competitor, the ASL—was playing. Partially out of a fear of losing top players to these other clubs during its off-season, by 1950 the NSL decided it needed to operate during those winter months.

Fortunately, an obvious option was available.

“Indoor Soccer Football”

While conventional wisdom is indoor soccer is something Americans invented in the late 1970s in order to get casual fans excited about a sport they were ignoring in droves outdoors, the fact is the indoor version of the game was well-established by the midpoint of the 20th century.

In fact, indoor soccer was played at least as early as 1885 when a Canadian XI that visited New Jersey to play an outdoor international also played a series of indoor games. Specifically, three games were played at the Olympian Roller Skating Rink, on Broadway, near 52d Street in New York.

While indoor soccer had been established, the sport was rarely seen as anything other than a wintertime training device. Some efforts to “professionalize” the sport were made, however. About 1911, the Metropolitan Association Foot Ball League of New York City arranged an exhibition match at Madison Square Garden during the annual track meet of Columbia University. Indoor soccer was also played at Madison Square Garden in the late 1920s where famous boxing promoter (but not yet New York Rangers owner) Tex Rickard staged games. Indeed, Chicago held indoor tournaments in the 1920s; similarly, full-sided indoor tournaments were staged at Boston’s Commonwealth Armory during the same period.

In 1939, the ASL decided to promote the game in earnest, and staged the first “professional” indoor matches in the country, at Madison Square Garden. The next year, indoor matches were again played at the Garden under the ASL aegis. A lack of fan interest, coupled with the United States’ entry into World War II, ended the series.

By 1950, however, the NSL remembered its earlier forays into indoor soccer a quarter-century earlier, and decided indoor soccer would be the ideal way to keep its players occupied (and, just as important, committed to NSL clubs) during the winter months.

At home in the cold

As all of the Major Division teams (as well as most of their players) were based in Chicago, it made sense that all of the indoor season’s matches would be played at a single, central location…one that would also be affordable: the Chicago Avenue Armory.

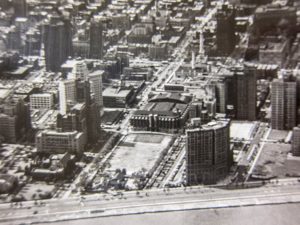

The Armory was built in 1916 for the 1st Calvary Illinois National Guard, and was situated on 220 East Chicago Avenue—between Lake Michigan and Michigan Avenue. It was demolished in 1993 to make way for the Museum of Contemporary Art, which currently occupies that location.

In 1921, the 1st Illinois Cavalry was reconstituted as the 106th Cavalry with regiments throughout Illinois. In 1925, the Armory added horse stables—and an arena. Used for many years to host polo matches among the horsemen in the infantry, the arena was significantly expanded in 1937.

(The Armory, 1935; photo courtesy Chicago Park District Special Collections)

The Rules

Obviously, the Armory was not built to with modern, domed stadiums in mind; it was a traditional arena. As a result, the indoor game as played by the NSL was a bit different from the outdoor version.

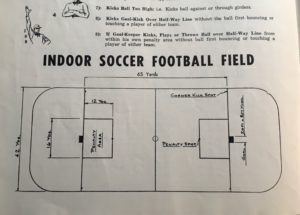

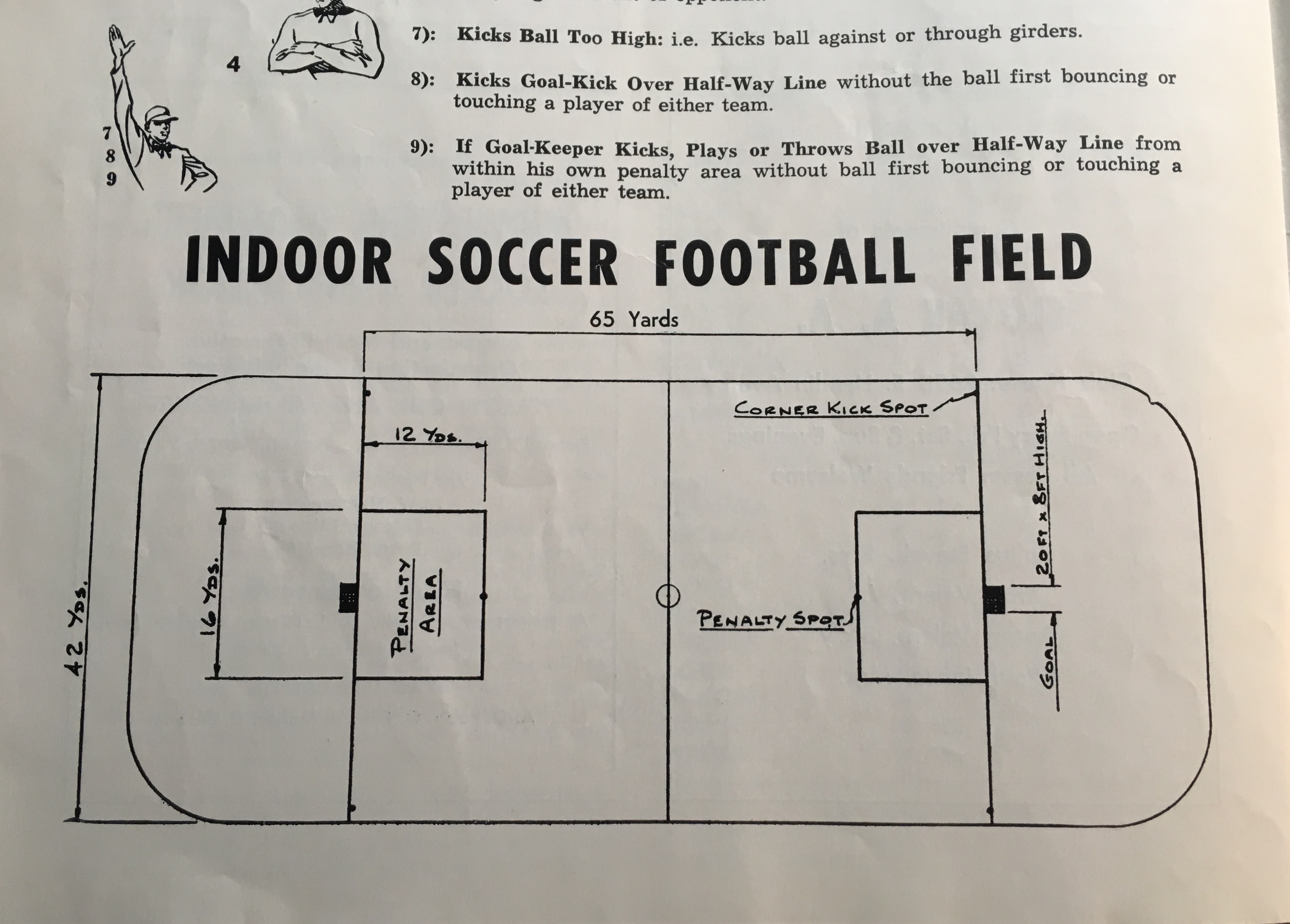

For that first season, games were played on a field 60 yards long and 42 yards wide, and allowed for the use of dasherboards, as in hockey—but only on the sides of the field; end lines were still in effect. The playing surface was a dirt floor, and only gym shoes (no cleats) were permitted. The goals were, surprisingly, not much smaller than regulation: 20 feet wide by 8 feet high. On free kicks, the wall only had to be 7 yards away. The offside rule was not in effect. Other changes included free kicks if the ball was kicked into the rafters, or if a goal kick crossed midfield without being touched.

Unlike in later versions of the game, free substitution was not the order of the day. Instead, subs were only permitted during goal kicks, or in the case of play being stopped for an injury.

Teams played seven a side, with two subs—game day rosters could carry 15 players, but only nine could be used in a match. The matches themselves were 20 minutes long—two 10 minute halves. These quick games were necessary to allow pretty full slates of matches to be played at the Armory—in the early years, six games would be played in two-and-a-half hours.

Coming in from the cold

On Sunday, January 1, 1950, the NSL inaugurated the first full indoor soccer season in U.S. history. Twelve teams participated in this first season, which ran for 13 consecutive Sundays (including playoffs).

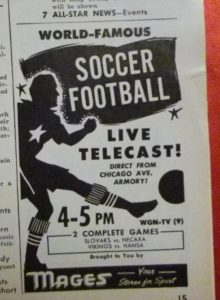

From the start, interest was high in the indoor circuit. Every week, WBKB-TV in Chicago would broadcast the full slate of games.

Competition was spirited. Vikings—middle-of-the-pack finishers in the outdoor campaign—went 9-1-1 to win the regular season title. However, it was 3rd place Eagles who surprised everyone to win the two game playoff series.

As might be expected in indoor soccer, goalkeeping was a valued commodity. Gino Gardassanich of Slovak was voted Most Valuable Player by his peers; his fine play helped get him selected to the U.S. World Cup team that summer, where he backed up Frank Borghi.

With the 1950 campaign an unqualified success, the following winter found the circuit expand by five teams. With the expansion, the indoor league went to two divisions. Rules were established which provided that the two leading teams in the First Division would be promoted to the Major Division, replacing the two bottom teams in the top bracket.

Again limited to Chicago-based teams, the 1951 season found Eagles winning a double of sorts, taking the Major Division crown to complement their 1950-51 NSL outdoor title. In the First Division, Falcons—augmented by a number of recent Polish DPs (“Displaced Persons”), went undefeated to earn promotion, along with runner-up Maroons; Necaxa and Hansa were the first teams to be relegated.

Profit and growth

After the first two seasons, the NSL’s indoor season had proven itself more than a mere winter diversion: it was both popular and profitable. As a result, the circuit continued through the 1950s.

In 1952, the season was shortened to 9 games from the previous 14. Nevertheless, the circuit topped the financial profit of the previous two seasons.

Lions won the Major Division by one point, going 6-0-3 (W-L-T) to Slovaks 5-0-4.

In a bit of a cautionary tale, newly promoted side Falcons never made it to the season, disbanding instead during the outdoor season. As a result, future seasons would find only one team being promoted and relegated between the divisions.

The transition between outdoor and indoor soccer was not always a smooth one, particularly for referees. One example of this occurred in mid-season. In a Major Division match between Lions and Necaxa (spared relegation by the demise of Falcons) with three minutes of play remaining in a scoreless match, referee Eli Korer awarded a foul against Necaxa for rough play. Don Stefanovich scored direct from the ensuing free kick, but Korer disallowed the goal on the grounds that it was an indirect kick. Under indoor rules, however, the only indirect kicks were for infractions such as kicking a ball into the rafters. As a result, Lions were later awarded the result, 1-0.

The winter of 1953 found the NSL looking to expand the indoor soccer concept even further. The league first held its normal indoor season, which was the most successful to date, topping all previous attendance records. Two games each Sunday were televised live on WGN-TV, with famed announcer Jack Brickhouse providing the play-by-play. Over 2,500 fans packed the Armory for the March 1 games, a new record in the Armory. A re-constituted Falcons side was restored to its Major Division status, and won the league on goal differential after compiling an identical 7-1-1 record with Hansa.

Given the great successes of the indoor circuit in four seasons, it is not surprising to find the NSL trying to expand the concept outside of Chicago. As a result, at the close of the regular season, the Armory played host to an Inner-City series: besides Chicago’s Falcons, Hansa, Spartans, and Eagles, the circuit included St. Louis Majors, Milwaukee Brewers (who also played in the NSL outdoor league and recently earned promotion to the top level), Toledo Turners, and Detroit Rangers. However, parochial Chicago fans were not interested in the out-of-town teams; attendances were half those of the regular circuit, and the series was discontinued after four weeks.

Indoor soccer continued to be successful throughout the 1950s; crowds continued to grow, and a four-team junior division was added in 1954 to allow for indoor experience for younger players.

In 1959, the Armory hosted what was billed as the first international game ever played indoors (notwithstanding the Canada games of 1885). Halsingborg of Sweden faced a Chicago All-Star team on March 13, drawing 5-5 before a crowd of 4,000.

The 1960s

Although the indoor league had gone from success to success in its first 10 years, the Space Age began rather ominously—there was no 1960 season, as the Chicago Avenue Armory was being used on Sundays by the National Guard Reserve for training.

Although the league returned for 1961, changes were afoot. The Major Division had 10 teams, and the First Division included 8 teams; however, it was announced the top division would be reduced by two teams for 1962.

As a result of these changes, Maroons and Red-White-Green, the two bottom finishers of the First Division, were dropped from the indoor league, and the three bottom-finishers in the Major Division (Fortuna, Wings, and Sparta) were dropped to the First Division.

The changes did not affect attendance in 1962, as over 18,000 fans attended over the nine weekends of play. In 1963, a record crowd of 2,497 packed the Armory in the last week of the season to watch Green-Whites take the title with a scoreless draw over defending champion Schwaben.

In 1963, the league continued to draw well, averaging about 2,200 fans per Sunday—again, however, this was to watch a full slate of games, not per match. Still, success was such that the NSL again tentatively attempted an inter-city competition, staging a one day “Mid-American” tournament. This tourney found the Chicago All-Stars routing St. Louis 6-nil and Milwaukee 8-nil before winning the event with a 3-1 win over Chicago Olympics.

The arrival of Beatlemania in 1964 did little to affect the success of NSL’s indoor league that winter. Attendance for the nine week season was announced as 23,992, averaging 2,600 per Sunday, with a record turnout of 3,048 on February 21. In 1966, total attendance was up to 24,047.

A Sunday at the Armory

The old Armory presented a pleasant diversion from the harsh Chicago winters, and a soccer fan could enjoy a full slate of games—the second division sides would provide early entertainment, followed by a youth game, followed by 2 hours of first division action before finishing up with some second division marches. A typical Sunday schedule would be as follows:

FIRST DIVISION

Wings v. Hakoah 12:30

Norge v. Adria 12:55

Slovak v. Wings 1:20

Lithuanians v. Fortuna 4:20

Red White Green v. Necaxa 4:45

MAJOR DIVISION

Hansa v. Kickers 2:15

Maroons v. Tanners 2:40

Rams v. Lions 3:05

Eagles v. Schwaben 3:30

Olympic v. Green White 3:55

JUVENILE

Kickers v. Youths 1:45

As can be seen, the 10 minute halves kept things moving. As might also be expected, the scores of matches were lower than what Americans would be accustomed to seeing in the major professional indoor leagues of later vintage: on one Sunday in 1966, for instance, the scores were: 2-1; 3-1; 4-1; 0-0; 1-0; 1-0; 0-0; 3-0; 0-0; and 3-1

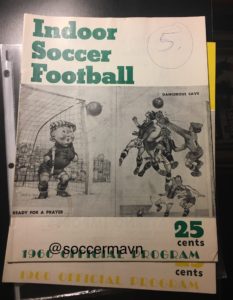

(1966 Official Programs; courtesy of author’s collection)

Consistent with the era, ethnic pride was in full bloom at the Armory, as well. Besides being evident in the team names, a quarter could get you an Official Program with ads promoting Hungarian food, various ethnic social clubs, trips to Italy, and German clothes.

The end of an era

The winter of 1967 found the NSL playing its usual indoor schedule, as well supported as ever. However, it was destined to be the last season. As reported in the 1967-68 USSFA Soccer Annual:

The regular indoor season, which has been played at the Chicago Avenue Armory every year since 1950, except 1960, will not be continued in 1968 and appears destined to be buried, unless a new home can be found. The Chicago Avenue Armory has a dirt floor which was ideal for soccer. A recent ruling by the State of Illinois ordered the floor to be converted to concrete from dirt. Officials of the indoor league considered the new surface would be too dangerous for the players, the therefore dropped the indoor league. As yet a suitable home for indoor play has not yet been located.

Although AstroTurf was a new sensation, it was obviously beyond the means of the NSL; as a result, the Armory was never again used for indoor soccer, and no other suitable facility was ever found.

As noted earlier, the Armory was demolished in 1993; in its stead now sits the Museum of Contemporary Art.

The spirit of the old NSL indoor seasons lives on, however–the league revived indoor play in the 1980s, and club teams continue to vie for titles.

Thank you Steve…very cool. UnionGoal

~

Form is temporary Class is forever.

.

This writing is Class.

Thank you so much!