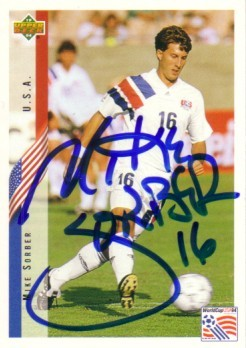

Two years before playing in front of 93,689 fans at the Rose Bowl against Colombia in the 1994 World Cup, the first World Cup game won by the United States in 44 years, Philadelphia Union assistant coach Mike Sorber was playing college ball in his home town at St. Louis University. 1992 would prove to be a momentous year for the then 21-year-old Sorber, earning both his first cap for the US national team and being named as a finalist for the Hermann Trophy.

At the 1994 World Cup, the US advanced to the Round of 16 where they were defeated 1-0 by eventual champions Brazil. Sorber started in all four of the US games in 1994, playing all but 15 minutes.

After the tournament, US national team head coach Bora Milutinovic would say of the young midfielder, “When you analyze the World Cup, Sorber was probably our MVP. It is difficult for me to explain what I feel about him. He is disciplined and intelligent.”

Soccer beginnings

Mike Sorber grew up in a soccer family in a soccer town. His father, Pete Sorber, was the head coach at St. Louis Community College-Florissant Valley where, over a 30 year career, he led the team to ten National Junior College Athletic Association championships.

“We lived one mile away and I had a big gym to play in and I, for the most part, played with older kids,” Sorber explained. “Everybody was three, four, ten, fifteen years older than I was. So, it was a pick up background — five-v-five, three-v-three — quite often.”

Like most soccer fans in the 1980s, connections to the international game were hard to come by. “Internationally, we didn’t have much in St. Louis,” Sorber described. “There was Soccer Made in Germany, so I saw a few games with Schumacher and Toby Charles was the announcer. That was about the only international exposure I had until there were a few national team games at St. Louis Soccer Park, a few qualifiers, a few friendlies. But really, St. Louis was a soccer community that has a rich tradition and a lot of good players came out of there. So that culture was already built in.”

The scarcity of coverage was also true when it came to the World Cup. “The World Cup final was on in ’86, but I only caught glimpses of it. Really, it wasn’t until 1990; I was home for the summer and it was on Univision, they had quite a few games. That was really my first World Cup exposure.”

Coming to the attention of the national team

The path to the national team through the US Soccer Development Academy system now seems simple: a young player advances through the age levels of one of the affiliated development academies, coming to the attention of the different youth national teams. But the current academy system was only founded in 2007. Before that, the main path to the national team was through US Youth Soccer’s Olympic Development Program, a fragmented system over which US Soccer had no control and little input. It was easy even for players within that system to fall through the cracks.

The path to the national team through the US Soccer Development Academy system now seems simple: a young player advances through the age levels of one of the affiliated development academies, coming to the attention of the different youth national teams. But the current academy system was only founded in 2007. Before that, the main path to the national team was through US Youth Soccer’s Olympic Development Program, a fragmented system over which US Soccer had no control and little input. It was easy even for players within that system to fall through the cracks.

Asked how he came to the attention of the national team in the lead-up to the 1994 World Cup, Sorber points to St. Louis University’s appearance in the Final Four of the NCAA championship tournament in 1991 when St. Louis faced Virginia in the NCAA tournament. Milutinovic was at the game to see Claudio Reyna play.

“It was just luck. We made it to the Final Four my junior year and we played Virginia. The coach came to watch Claudio Reyna, and we played against each other. So, it was in that game that he spotted me and I got invited to a camp in December. There were about 30 guys, not just college guys but some other indoor professionals, and from that they took five of us and we started training with the first team in January.”

On January 25, 1992, Sorber earned his first cap with the national team in a 1-0 loss to the Commonwealth of Independent States, a team made up of players from countries that had been part of the Soviet Union. Over the next month and a half, Sorber would be with the US team for five road games against Costa Rica, El Salvador, Brazil, Spain, and Morocco, making four appearances, each of which he went the full 90 minutes (he didn’t play against Brazil).

Said Sorber, “That really propelled me all the way to the World Cup.”

Meanwhile, Sorber returned to St. Louis to finish out his final year in college, all the while making periodic appearances with the national team. In 1992, Sorber was named as a finalist for the Hermann Trophy, which was won that year by Brad Friedel.

“So, instead of playing as a pro, getting ready for the World Cup, you’re in college,” Sorber said with a chuckle. “That’ll never happen again.”

The run-up to the World Cup

In January of 1993, Sorber was with the national team’s pre-World Cup residency camp in Mission Viejo, California. In the absence of an American first division soccer league, the residency camp had been established to ensure that national team players could train full time. The players still had to earn a living, so they signed contracts with the federation.

“It wasn’t even labeled a program,” Sorber said. “There was no league, it was just preparation.”

“They housed us in apartments for that year-and-a-half,” he explained. “Again, we had anywhere from 24 to 30 guys, different players came in and out. They gave us year-long contracts but they were minimum salary, $24,000 to $60,000 — I was on $24,000 for a year-and-a-half.”

As host, the US had an automatic spot in the 1994 World Cup. And while the perils of qualification would not be missed, the team lost out on the opportunity to compete against other national teams, usually a major determinant of who makes the World Cup squad. To address this need for quality opponents, the federation organized an unprecedented match schedule that, between 1992 and the start of the 1994 World Cup, featured 73 games, including friendlies, mini tournaments like the US Cup and Kirin Cup, and the 1993 Gold Cup. That schedule, along with the fact that players were living and training together, produced in a club-like atmosphere within the team.

“That’s what they were trying to create,” said Sorber, who appeared in 36 of those matches. “That’s what we had to create. We needed the games for experience, we needed the games for fitness, for working on different details. You can’t just train it, you have to put it to the test in games, so they got as many games as possible, which really helped prepare us for once we started the World Cup.”

Making the World Cup squad and the Nutty Professor

Before he was hired to coach the US team in 1991, Bora Milutinovic had taken Mexico to the quarterfinals of the 1986 World Cup, and Costa Rica to the Round of 16 in 1990. Then US Soccer president Alan Rothenberg called him “the Miracle Worker.” In the cover story for the July 4, 1994 edition of Sports Illustrated, writer Alexander Wolff called the Serbian-born coach — who was less than fluent in English — a “witch doctor”: “Mystical and inscrutable, a man who communicates with indirection and shoulder shrugs.”

Sorber’s memories of Milutinovic are informed more by what Milutinovic actually brought to the team as a coach than by his mannerisms with an American press corps that was largely made up of reporters who were new to soccer.

“Bora was actually a pretty simple soccer mind,” Sorber recalled. “He had a good picture of what he wanted, and had a good idea of what was important soccer-wise for US. But because of the language barrier –I think people are looking for a complex formula, or a secret, or something that they don’t quite understand. And so Bora, in his way of speaking, would in trying to describe things in a simple way — people thought there must be more to this.”

That “simple soccer mind” was exactly what the US needed.

“We would have long trainings because there was a lot to cover and a lot to learn,” Sorber explained. “So, he would break it down to fine, minute details that were very basic, very simple. The American players and coaches weren’t used to that much detail, it was more about fitness, more of the physical aspects of the game, where he was more about the soccer details, how it would fit together — how to move the ball around, how to move together, how to stay connected… Everything that’s soccer that’s so basic, but everybody’s kind of looking for special tactics, or something that really doesn’t exist. So he was kind of labeled the nutty professor.”

Judging by reports from the time, Sorber’s inclusion in the team seems to have struck some as a surprise. After all, he was a 23-year-old kid fresh out of college, receiving his degree from St. Louis University the same year he was playing in a World Cup. Sorber’s role on the team grew in importance ten days before the start of the Cup when Claudio Reyna, the player Milutinovic was scouting when he spotted Sorber – tore a hamstring. Even as it became clear that Sorber would play a big role during the tournament, the player himself struggled to explain what made him stand out. When Sports Illustrated’s Wolff asked Sorber why he was in the squad, he got an honest response: “Another Bora mystery.”

Reminded about the quote now, Sorber considers the context of the times. “People struggled to understand soccer in this country, no one really had a good reference point, so, I’m not sure what they were looking for. But, I was never — I didn’t have the hair, I didn’t have a certain flashy style, I just had a soccer brain, and I was an important piece to the team. But, most soccer writers couldn’t understand what that meant. So, anytime they would discuss potential picks — much like they do now — one, I wasn’t talked about, or two, they would say there’s no chance this guy’s going to make it. And then, once I did make it, then they couldn’t understand that. And then I started every game, and I was an important piece for the team, and they still couldn’t understand it.

Reminded about the quote now, Sorber considers the context of the times. “People struggled to understand soccer in this country, no one really had a good reference point, so, I’m not sure what they were looking for. But, I was never — I didn’t have the hair, I didn’t have a certain flashy style, I just had a soccer brain, and I was an important piece to the team. But, most soccer writers couldn’t understand what that meant. So, anytime they would discuss potential picks — much like they do now — one, I wasn’t talked about, or two, they would say there’s no chance this guy’s going to make it. And then, once I did make it, then they couldn’t understand that. And then I started every game, and I was an important piece for the team, and they still couldn’t understand it.

“It’s interesting what perceptions are, or how things get labeled. Yet, if you go to Barcelona and your Busquets, or if you’re on Real Madrid and you’re Xabi Alonso, two guys from Spain, there’s an appreciation for that style — or in Mexico, for a guy that is sort of the quarterback and organizes things, and helps connect all the pieces on the team. Everybody’s looking for a big, physical presence, or someone more creative, or someone that scores. They don’t quite understand the importance of a good center midfielder, although I think there’s a little more appreciation today with Michael Bradley, Ricardo Clark, Mo Edu, Kyle Beckerman, those types of players.”

Sorber would play in all but 15 minutes of the four US games at the 1994 World Cup, partnering with his roommate Thomas Dooley. “Dooley was a great player,” Sorber said. “He was so mobile, he could cover a lot of ground, so he really had the freedom to go forward and do more of that role, where my responsibility was more to hold down the fort and connect all the pieces, and sort of play off the way the game was going. I think we formed a good relationship and it was an important piece, the two of us and the way we played, to the success of the group.”

Playing at the 1994 World Cup

The US played in front of massive crowds in 1994: 73,425 against Switzerland, 93,689 against Colombia, 93,869 against Romania, 84,147 against Brazil. Sorber remembers the crowds inducing less anxiety than one might think.

“That’s why we played some of these friendly games, so it wasn’t an intimidating factor,” he said. “Whether there’s 20,000 or 100,000, it’s pretty similar. Yes, it’s more people, but the noise, it’s kind of similar. Whether it’s 20,000 or 100,000, the decibel level seems to be the same. But, once you get to the World Cup, now it counts, now the spotlight is really on you, and every play, and every action, matters — for you or against you.”

The US played its first game at the 1994 World Cup on June 18, a 1-1 draw with Switzerland indoors at the Pontiac Silverdome. The heat inside has often been remarked upon, but the field itself, which consisted of grass on a system of trays, was actually quite good. “It wasn’t spongey, the field was perfect,” Sorber recalled. “It was carpeting, it was like a pool table, one of the best fields I ever played on. We were the first game on it, the seams had come together. It was firm, fast, it was awesome.”

However, the rest of the conditions in Detroit were tough, as they were in all of the games.

“It was a dome and it was humid inside, but we didn’t have the direct sunlight like we did against Colombia, and Romania, and Brazil,” Sorber explained. “But it was still hot. It’s kind of funny seeing these guys struggling in the NBA finals. They get, what, 40-plus timeouts to hydrate, to sub people out, and yet they’re struggling in 90 degrees, when it might of been 90 or 100 in that dome, and it was 120 (on the field) in a lot of the games at the World Cup.”

“Detroit was great, because I thought it was a pretty pro-American crowd.” Sorber continued, “In the Colombia game, I think when you look at the pictures, there seems to be a bit more yellow in the stands, but after the game there’s more red, so I don’t know if they had two jerseys or what happened, but it was a great moment to be on the field and to finally have a result against a really good opponent. Everybody in our group was a good opponent but it was great to get that one for sure.”

The US may have been the host but that did not guarantee their group would be weak. “Switzerland, to this day, is a good opponent,” insisted Sorber. “They’re disciplined…they’re very good, they’re hard. Then you go to Colombia, definitely a more South American style with short passing and more cleverness, with some really good athletes. I mean Colombians are today some of the better players in the world. And then you got to Romania and they’re a mix of both…And ultimately, you finish with Brazil, one of the best teams in the world.”

Before the US could face Brazil in the Round of 16, they had to get a result against Romania. Already with four points after the draw with Switzerland and win over Colombia, a point against Romania would guarantee knockout round play for the Americans. Instead, the US lost 1-0 and had to wait two days to learn if they would make it through.

“We knew we were in a good place,” Sorber said of the wait the team had to endure before it would know its fate. “We did everything that we could in those three games. We had four points and history would tell you that with four points you would most likely get through. So, I think we felt confident about it but, ultimately, we had to wait until it was official.”

The first half of the game against Brazil ended scoreless, but will be forever remembered for the red card Brazil’s Leonardo received for an elbow that fractured Tab Ramos’ skull. Sorber said Ramos’ departure affected the game more than Leondardo’s exit, “Really, the only thing it changed was that it took Tab off the field. He was a key piece as far as somebody that could create, help set up, which he did in the other three games.

“And so, now he’s out for the second half. Now it’s an opportunity for the next guy to step on with some fresh legs. I think we had a pretty good second half and made a good push, but, unfortunately, we came up a little bit short.”

The American soccer player’s burden

The 1-0 loss to Brazil came exactly six years to the day after FIFA announced the US would be the host of the 1994 World Cup. In addition to hosting the 1994 tournament, the US made their first appearance at the World Cup in 50 years in 1990. Since that tournament, the US has had an unbroken run of qualifying for World Cups: Seven for seven. And that success has greatly contributed to the birth and continued growth of a domestic soccer league.

Two years after the 1994 tournament, the first game was played in Major League Soccer. Sorber and the rest of the players on the 1994 team couldn’t have known just how their performance would be a spark for the continued development of the game in the US, they did have an awareness of their responsibility in laying the foundation for the game’s future in this country.

But the more salient responsibility was those first three games in 1994.

“I think we did have a sense that we had a big responsibility,” Sorber said. “No host country had not progressed to the second round — it finally happened in 2010 with South Africa. So, it’s a major, major challenge that I think a lot of people didn’t grasp or understand coming into it, and had pretty much written us off.”

That understanding of how so many observers – domestic and international – dismissed the US connects with the long term legacy of the 1994 team.

“It’s sort of that weird perception of, you know, ‘Oh, the US is no good.” It’s still a label that our players battle through and fight with trying to earn their respect. Whether it’s Bob Bradley coaching or Michael Bradley playing, or Clint Dempsey, or Landon Donovan, or any of the other guys who’ve gone to Mexico or gone to Europe, there’s always that responsibility as an American to sort of open doors for others that will come behind you, and to prove that we have some talent, and that we can have individuals that will fit into a group or a team, and make them better. So, I don’t think we could fully grasp the scale of what was to come afterwards, but we knew we had a good opportunity and we had a big responsibility to lay the foundation and make a good impression.

“I think we proved that we were up to the challenge,” Sorber continued. “We were ready for that and, as a group, I think we had some really good performances that, like everything else, helped give the country some hope, some dreams for the future. It was a real good foundation that was laid that has continued to grow as we move through the process of being a soccer nation.”

Sorber’s future would include two seasons in Mexico’s top flight with Pumas, where he became the first US player to be named a Mexican first division all-star. In 1996, he joined MLS, where he played for five seasons before retiring after the 2000 season to become an assistant coach at his college alma mater. In 1998, Sorber was named as an alternate for the US World Cup squad but did not travel with the team to France. In 2007, Sorber became an assistant coach with the US national team, and was with the US at the 2010 World Cup. He then joined the MLS coaching ranks, first as an assistant with Montreal Impact and, since the last offseason, with Philadelphia Union. Quite a journey for a guy whose soccer career began with pick-up games against the older kids and who says it was luck that first brought him to the attention of the national team.

When reminded of the Milutinovic’s quote describing him the 1994 US World Cup team’s most valuable player, Sorber responded, unsurprisingly, like the team player that inspired the quote.

“It’s great, I appreciate the comment. But I think as a group, more importantly, we had a lot of talented players, and we proved that we could play. Were we better? No, we weren’t necessarily better, but on any given day we could compete, and we could get results. I think a lot of people watched it and it gave people a lot of hope for the future. To be a part of that, and to have that quote is nice because I know the hard work and the effort that I put into trying to help the team and be a part of that group.”

Great interview, Ed! Strong work. Quick question: does he stay with the Union with Hack’s termination and work for/with Curtain?

Thanks, Brian! It looks like he’s staying, Curtin talked about the two of them working together in Thursday’s press conference.

I should say that I interviewed Sorber last Saturday before the game against Vancouver. I had arranged to interview him strictly about his World Cup experiences so I didn’t ask any questions about the Union.

Great read, Ed.