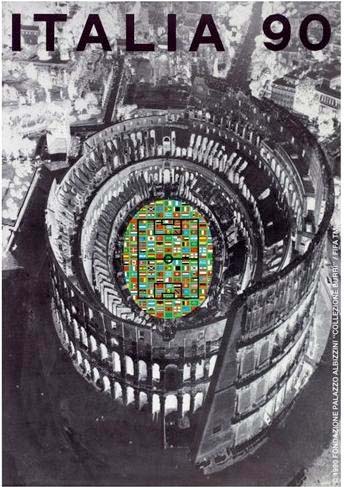

Our series on the US and the World Cup continues with a look at the 1990 World Cup in Italy, the first the US had qualified for in forty years.

Our series on the US and the World Cup continues with a look at the 1990 World Cup in Italy, the first the US had qualified for in forty years.

The lead up to the 1990 World Cup

On Independence Day, 1988, FIFA announced that the United States would host the 1994 World Cup.

Despite the fact that the US had failed to qualify for the World Cup for 38 years and lacked a genuinely professional outdoor league, FIFA sensed an opportunity.

The US-hosted 1984 Summer Olympics had been spectacularly successful with the organizers reporting a surplus of $200 million. Despite the fact that ABC’s coverage of soccer at the 1984 Games was practically nonexistent, more than 1.4 million people had attended the matches of the Olympic soccer tournament with an average of 44,500 per game. Some 78,265 turned up to see the USA vs. Costa Rica match on July 29, 1984, topping the previous record for home attendance of a US national team match by 45,000. The final between France and Brazil drew nearly 102,000 spectators to the Rose Bowl.

As one member of the Brazilian delegation said of the selection of the US as a World Cup host country and soccer in America, “A lot of people can make a lot of money if the games take off.”

If the US was to have any credibility as a host country, David Wangerin writes in Soccer in a Football World, “reaching Italy in 1990 was now imperative.”

Considering the series of failed attempts to qualify for the nine consecutive World Cups after the 1950 tournament, the US would get two very lucky breaks in their qualification campaign for 1990. First, Mexico was disqualified from participating in the 1990 World Cup for fielding over-age players in a FIFA youth tournament (the Mexico soccer yearbook had helpfully published the players’ birth-dates) and then Canada was eliminated by Guatemala in the preliminary round of qualifiers.

Roger Allaway and Colin Jose describe in The United States Tackles the World Cup that a myth soon grew in some circles that the US owed its eventual qualification for the 1990 World Cup to the fact that Mexico had been disqualified. They note, however, that “the team that finished ahead of the United States was Costa Rica, which had been drawn against Mexico in the first round and got a bye into the second after Mexico was disqualified. If Mexico had not been disqualified, Mexico and Costa Rica could not have both finished ahead of the United States, because one of them would have been knocked out by the other in the first round.”

Warming up for the qualifiers

Before the preliminary round of qualification, which would take place for the US in the form of a two-game series against Jamaica in the summer of 1988, the US played a series of games against international opponents, finishing with decidedly mixed results. In all, some 14 internationals were played that year but Colin Jose and Roger Allaway note in The United States and World Cup Soccer Competition that “in only four did the US field what could be considered its full international team” seeding the rosters for the other games “with a number of young players, giving them international experience.”

The year began with a 1-0 loss to Guatemala in Guatemala City on January 10, 1988. Three days later, the US defeated Guatemala by the same score. On May 14 in Miami, the US lost 2-0 to Colombia.

The US then played seven games in the Clasico International Cup tournament, starting with a 1-1 draw with Chile in Stockton, California on June 1. Two days later in San Diego, Chile won again, this time 3-1. In Fresno on June 5, Chile defeated the US, 3-0. On June 7 in Albuquerque, Ecuador defeated the US, 1-0. The US lost 2-0 to Ecuador in Houston on June 10 before drawing with them 0-0 in the second game two days later in Fort Worth. On June 14, the US finished out the tournament with 1-0 win over Costa Rica.

Jose and Allaway note that, of the seven games the US played in the Clasico International Cup tournament, “only two can be regarded as full internationals because the US fielded a team that was well below full strength in the other games.” The reason for this was that the US was participating in the 17th annual President’s Cup in South Korea ahead of the Olympic tournament in that country later that summer. The President’s Cup featured a mixture of national team and club sides and the US was drawn in Group D along with a Soviet Union XI (the full Soviet team was participating in the European Championship), Nigerian club side Iwuanyanwu Nationale, and England’s Queen’s Park Rangers. The US opened group play with a 1-0 loss to the Soviet Union on June 16 before falling 3-2 to Iwuanyanwu Nationale on June 16. Its tournament run ended with a 1-1 draw with QPR on June 21.

On July 13, the US fell 2-0 to Poland in New Britain, Connecticut. Its first game in the preliminary qualification round for the 1990 World Cup would take place eleven days later.

The US nearly doesn’t make it out of the preliminary qualification round

The first US match in the qualifiers for the 1990 World Cup was away against Jamaica. The game, which took place in Kingston on July 24, 1988, ended as a 0-0 draw. Unless the US could win the return leg on August 31, 1988 at St. Louis Soccer Park in Fenton, Missouri, it would be out of qualification.

The first US match in the qualifiers for the 1990 World Cup was away against Jamaica. The game, which took place in Kingston on July 24, 1988, ended as a 0-0 draw. Unless the US could win the return leg on August 31, 1988 at St. Louis Soccer Park in Fenton, Missouri, it would be out of qualification.

With less than 30 minutes to play in the second half, the US, whose starting lineup featured five players with no club affiliation, was tied with Jamaica 1-1 after a goal from Brian Bliss and the embarrassment of an early exit was a very real possibility. Spurred on by the substitution of Hugo Perez, and taking the lead off of his penalty kick goal in the 68th minute, the US finished the match with as 5-1 victors with additional goals from Paul Krumpe and Frank Klopas, who scored a brace.

US Soccer for once recognized that more needed to be done to improve the team’s qualification chances — the stakes were simply too high. Wangerin writes,

Within hours of the victory the USSF announced that it would sign players to contracts of its own, assuring them of a modest salary and committing them to the national team, though allowing them to be loaned to other clubs. “Playing regularly on the highest level is of the utmost importance for the players,” maintained Werner Fricker [president of the USSF and former player for Philadelphia’s United German Hungarians] — an aphorism uttered by many of his predecessors which, at last, seemed more than simply rhetoric.

Bob Gansler became the full time coach of the US team, replacing the part time Lothar Osiander, who had continued to work as a waiter in San Francisco during his time as national team coach. Osiander had coached the US through qualification for the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul and at the Games, where the team tied 1-1 with Argentina in its opening match on September 18, played to a scoreless draw with South Korea on September 20, and then fell 4-2 to the USSR on September 22. Joining Gansler in guiding the team through the remaining qualifiers would be Philadelphia soccer legend Walt Chyzowych as the US Soccer Federation’s national director of coaching.

Still, the organizational inexperience of the federation remained apparent as the team headed into the round-robin portion of the qualification.

The US in the qualification round-robin

In its first match of the round-robin portion of World Cup qualification, the US faced Costa Rica away on April 16, 1989 at the National Stadium in San Jose. The US lost 1-0. Allaway and Jose write in The United States Tackles the World Cup, “speculation that the United States had a realistic chance of qualifying for the World Cup finals this time around had ballooned into talk that the Americans were the CONCACAF favorites.” It was now clear that if the US was to qualify “it would have to play catchup in the group standings throughout the seven-month competition.”

For the return leg on April 30 in Fenton, the US was able to protect a 1-0 lead after Tab Ramos scored, thanks in part to two Costa Rica goals being disallowed and to goalkeeper David Vanole’s 88th minute penalty kick save. Wangerin relates that the “raucous support” for the Costa Rican team at the game was so loud that it “produced pleas from the public address announcer to ‘remind the players what country the game is being played in.'”

Two weeks later on May 13, the US faced Trinidad & Tobago in Torrance, California’s Murdock Stadium, a stadium where the pitch was barely 70 yards wide, was discovered to have been mismarked only hours before kickoff, and also had been vandalized the night before when someone had driven a car over the field. Steve Trittschuh scored to give the US a 1-0 lead going into the second half but in the 88th minute the visitors equalized to get a share of the points.

Two weeks later on May 13, the US faced Trinidad & Tobago in Torrance, California’s Murdock Stadium, a stadium where the pitch was barely 70 yards wide, was discovered to have been mismarked only hours before kickoff, and also had been vandalized the night before when someone had driven a car over the field. Steve Trittschuh scored to give the US a 1-0 lead going into the second half but in the 88th minute the visitors equalized to get a share of the points.

To prepare for its next qualification game, the US played Peru in a friendly at Giants Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey, on June 4, 1989, emerging the 3-0 winners. On June 17 the US qualification campaign righted itself with a 2-1 victory over Guatemala at Veterans Memorial Stadium in New Britain, Connecticut, thanks in part to a Guatemala own-goal after Bruce Murray scored. The US now had five points from its first four games. But with three of the remaining four games away against El Salvador, Guatemala, and Trinidad & Tobago, a tough road was ahead.

The US played several warmup games over the summer before it faced El Salvador, and the results were not what would have been hoped for. In Miami on June 24, the US lost 1-0 to Colombia. In the Marlboro Cup in Los Angeles, the US lost 2-0 to Juventus on August 10 before being defeated 2-1 by South Korea on August 13. Two other friendlies saw better results, a 1-0 win over a side representing the Irish League of Northern Ireland in July in New Britain Connecticut and a 1-0 win in August over Dnipro Dnipropetrovsk, the Ukrainian team that had won the Soviet championship in 1988. That game took place at Franklin Field in Philadelphia in front of more than 43,000 spectators.

Fortunately for the US, FIFA had ordered that El Salvador play its final three games on neutral ground because of persistent crowd trouble. In front of fewer than 4,000 spectators in Tegucigalpa, Honduras on September 17, 1989, a goal by Hugo Perez, who had been born in El Slavador, gave the US a 1-0 victory and the team was now in third place with seven points and three games remaining. Second place Trinidad & Tobago had nine points with one game left and first place Costa Rica had played all of its matches to finish with eleven points.

On October 8, the US managed a 0-0 draw against Guatemala at the Estadio Mateo Flores in Guatemala City, a disappointing result considering that Guatemala had already been eliminated. The 0-0 draw on November 5 against El Salvador, who was also by now eliminated, was even more disappointing for occurring at home in the US at the St. Louis Soccer Park. If the US had won this match it would only have needed a draw against Trinidad & Tobago away to qualify for the 1990 World Cup.

Wangerin writes that, for the US, “Elimination would not only erode the federation’s credibility as a World Cup host but also threaten its financial position — it had borrowed half a million dollars to underwrite the national team, with the clear expectation of reaching Italy.” Mike Windischmann, the new captain of the US team said to his teammates, “Don’t you realize if we lose some of us will have to go out and get jobs?”

Five days before the most important US national team game in decades, the US defeated Bermuda 2-1 in front of only 2,000 spectators in Cocoa Beach, Florida. On November 19, 1989, some 35,000 spectators crammed into Trinidad & Tobago’s National Stadium in Port-of-Spain to cheer on their home team.

Needing an attacking side to better improve his team’s chances of securing a win, Gansler made four changes to his lineup, including starting Paul Caligiuri. This decision delivered in the 31st minute when Caligiuri received a pass from Tab Ramos, moved past one defender with a tidy flick, and then struck a left-footed volley from 25 yards out that took the Trinidad goalie completely by surprise to find the back of the net.

Caligiuri’s strike was quickly dubbed “the shot heard round the world” by the American press and, finishing qualification in second place, the US was on its way to Italy. While Joe Gaetjen’s goal in the US victory over England in the 1950 World Cup is probably more historic internationally, Caligiuri’s goal is unquestionably more important in terms of US soccer history as the catalyst for seven consecutive World Cup qualifications.

World Cup warm-up games

The US played a series of warmup games against opponents of decidedly mixed quality in 1990 in the lead-up to the World Cup in Italy, finishing with a 6-6-0 record. At the Miami edition of the Marlboro Cup, the US was defeated 2-0 by Costa Rica on Feb. 2 and then lost to Colombia on February 4 after penalty kicks when the game ended tied at 1-1. Things began to look up after a 1-0 win away over Bermuda on February 13 before the team closed the month with a 3-1 loss to the USSR in Palo Alto, California on February 24.

The US next defeated Finland 2-1 in Tampa on March 10 before finishing the month in Europe with a 2-0 loss to Hungary in Budapest on March 20, and a 3-2 loss to East Germany in East Berlin on March 28. The US then defeated Iceland 4-1 on April 8 in Fenton before losing 1-0 to Colombia on April 22 in Miami. Two final games were played in the US in May before the team left for Europe. On May 5, the US defeated Malta 1-0 in Piscataway, New Jersey before defeating Poland on May 9 in Hershey, Pennsylvania in front of 12,000 fans.

In its final games before the World Cup tournament, the US defeated home team Lichtenstein 4-1 in Eschen Mauren on May 30 before being defeated 2-1 by Switzerland on June 2 in St. Gallen.

The US at the 1990 World Cup

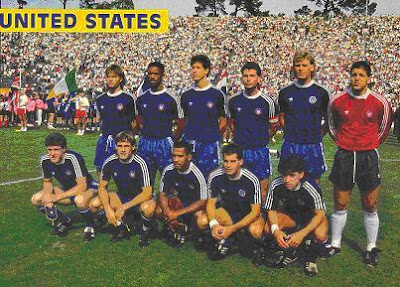

The US entered the World Cup in Italy with a roster whose average age was 23 and included three players who were still on college teams. US head coach Bob Gansler, who expected to make it to the second round, said of the team’s tactical philosophy, “Our formula is simple: 11 guys play offense, and 11 guys play defense.” The English football journalist Brian Glanville dismissed the US team as a “galumping side of corn-fed college boys.” But as Wangerin notes, “if their university experience and its emphasis on structured, disciplined team play did not lend itself to creative freedom and ball artistry, it had certainly built a competitive psyche and an indomitable spirit.”

The US was drawn into Group A with Italy, Czechoslovakia, and Austria. On June 10, 1990, that “competitive psyche and an indomitable spirit” would be severely tested when the US faced Czechoslovakia at the Studio Comunale in Florence. Of the eleven US starters in the game, only Willingboro, New Jersey’s Peter Vermes, who played for Volendam in the Netherlands, was not under contract with the federation via the program that had begun two years before.

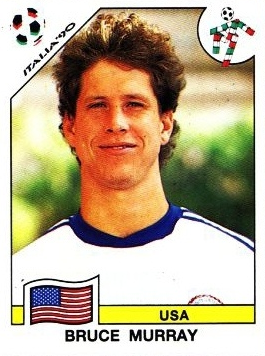

For the first fifteen minutes of the match the US must have been encouraged as the Czechs probed the US formation. Then, in the 25th minute, Tomas Skuhravy scored the first goal for the Czechs. Michal Bilek tallied the second in the 39th minute on a penalty kick. Ivan Hasek made it three goals in the 50th minute. After the 51st minute the US were down to ten men when Eric Wynalda was ejected for striking Josef Chovanec. Paul Calgiuri pulled one back for the US to make it 3-1 in the 61st minute. Stealing the ball near the center circle, he passed to Bruce Murray, who passed the ball back to Calgiuri, who then broke free down the center of the pitch. Avoiding a tackle, and Calgiuri rounded the keeper and finished from 12 yards out. A second goal by Skuhravy in the 78th was followed by a Milan Luhovy goal in stoppage time and the final score was Czechoslovakia 5, USA 1.

The New York Times said that the US team had been “humiliated to the point of embarrassment.” The London Times reported that the US “were utterly exposed by such Bronze Age devices as an overlapping full-back.” The headline in Milan’s Corriere della Sera read, “USA, What A Delusion.”

The next match was on June 14 against Italy in Rome and when Giuseppe Gianni scored in the 11th minute, most observers probably settled in for a goal fest. Instead, in front of some 73,000 fans at the Stadio Olimpico in Rome, the US almost produced one of the shocks of the tournament.

Whereas the US lineup had been geared for attack against Czechoslovakia, against Italy the team played a defensive game. Allaway and Jose write that, when Gianluca Vialli missed a penalty kick in the 19th minute, “Italy never regained its momentum and the roaring Roman crowd gradually turned quiet.”

In the 70th minute the US nearly equalized when Italian keeper Walter Zenga couldn’t hold on to a free kick from Bruce Murray. Vermes struck the rebound but the ball was cleared off the line.

After the match the Italian manager Azeglio Vicini declared, “The Americans proved they are an excellent team, nothing like the team that lost 5-1.” Gansler said, “this is the US team I know.”

The final match against Austria in Florence on June 19 at Stadio Comunale was a nasty affair and resulted in thirty-seven fouls and nine bookings. Despite playing a man up tafter Austria’s Peter Artner was ejected from the match in the 34th minute, the US conceded first when Andreas Ogris scored in the 52nd minute. In the 65th minute, Gerhard Rodax made it 2-0. Bruce Murray scored for the US in the 85th minute when he finished a short cross from Tab Ramos into the goalmouth and the game ended in a 2-1 defeat for the USA.

The final match against Austria in Florence on June 19 at Stadio Comunale was a nasty affair and resulted in thirty-seven fouls and nine bookings. Despite playing a man up tafter Austria’s Peter Artner was ejected from the match in the 34th minute, the US conceded first when Andreas Ogris scored in the 52nd minute. In the 65th minute, Gerhard Rodax made it 2-0. Bruce Murray scored for the US in the 85th minute when he finished a short cross from Tab Ramos into the goalmouth and the game ended in a 2-1 defeat for the USA.

After 40 years of waiting, it was three matches, three losses, and the US was headed home.

Italy would lose on penalty kicks against Argentina in the semifinals. Czechoslovakia would lose to the eventual winners, West Germany, in the quarterfinals.

After the 1990 World Cup

While the US had improved through the course of the World Cup, it was clear that the lack of professional league experience was a major factor in its poor performance. And while the program of friendlies before the World Cup was a great improvement over earlier preparations, Wangerin writes that the “endless string of exhibitions against half-interested opposition had left the Americans unprepared.”

Only four players on the US 1990 World Cup team had European experience. After the tournament, twelve of the seventeen members of the team who had appeared in the games in Italy would sign with European clubs, providing invaluable experience to the national team program.*

Equally important was the federation program that began in 1988 of signing players to national team contracts to provide them with a living wage and the opportunity to train full time with the national team or go out on loan, particularly to the American Professional Soccer League, the league that in 1993 would lose out to MLS in its bid to secure sanctioning as the first division of the US soccer pyramid, a requirement from FIFA for awarding the hosting rights for the 1994 World Cup to the US. Originally involving 14 players, some 30 players had participated in the federation program when it was ended in 1994.

Meanwhile, if the 1994 World Cup was to be any kind of a success, the federation would have to sell the tournament not only to the American public, but to corporate America.

*They were, with greater or lesser degrees of success: Brian Bliss for Carl-Zeiss in Germany; Paul Caligiuri, who had earlier played for SV Meppen, went on to play for Hansa Rostock, Freiburg and St. Pauli; John Doyle for Orgryte in Sweden and Vfb Leipzig; John Harkes for Sheffield Wenesday, Derby County, and West Ham; Kasey Keller for Milwall, Leicester City, Rayo Vallecano, Tottenham Hotspur, Southampton, Borussia Mönchengladbach, and Fulham; Tony Meola for Watford; Bruce Murray, who had earlier played for Luzerne, later played for Milwall; Tab Ramos for Figueras and Real Betis; Chris Sullivan, who had earlier played for Le Touquet, was with Raba ETO Gyor in Hungary and later played for Brondby in Denmark; Steve Trittschuh for Sparta Prague (with whom he became the first US player to appear in the European Championship Cup tournament, now known as the UEFA Champions League) and Dordrecht in the Netherlands; Peter Vermes, who had earlier played for Raba ETO Gyor, was with Volendam in the Netherlands in 1990 and later played for Figueras; Eric Wynalda for Saarbrucken and Bochum.

November 19, 1989: “The goal heard round the world”

June 10, 1990: USA 1-5 Czechoslovakia

June 14, 1990: USA 0-1 Italy (complete game)

June 19, 1990: USA 1-2 Austria (complete game)

Official USA 1990 World Cup song “Victory,” by Def Jef & DJ Eric Vaughn

A version of this article was originally published on May 6, 2010.

I remember watching this game back in 1989 on ESPN. Seemed no one else really cared much, but at the time I thought this was the most important game in US Men’s Soccer history, and I still do today. I am starting a blog on my World Cup experiences and the upcoming World Cup in Brasil

I was fortunate enough to play with Mike Windischmann and Brian Bliss in college, Yes, I played at both schools they attended and was lucky enough to play next to Windy as a kid. The other fond memory is play against Bruce Murray while he was at Clemson, he scored some goal back then,and played against him in my youth when my bunch from Long Island would go down to the DC area at Thanksgiving, he was some player as a kid as well. Thanks for the smile.

Does anyone know the USA preliminary roster of the World Cup 1990, 1994 and 1998 ?

You write “Gianluca Vialli missed a penalty kick in the 19th minute.” The missed PK took place about the 33rd or 34th minute of the Italy match — the foul is at 33:29 of the video, and the PK itself is at 34:36.

Note: although the Italy video is captioned as being the “complete game,” it’s missing the last several minutes of the first half. It breaks off immediately into the second half at 43:39 of the video, picking up the action, it appears, just a few seconds after the second half kickoff.

¶

The free kick leading to Vermes’s near-score is at 1:06:54 of the video. Vermes’s shot neatly nutmegged Zenga; only because the keeper improvised instantly, and tried to sit on the shot, managing to get a piece of the ball with his posterior, was it slowed and slightly diverted enough that the defender Riccardo Ferri had the opportunity to step off the line and clear it away.

¶

Amazingly, Vermes was the only U.S. player following the free kick in. Everyone else was way back, and by the time they tried following in Vermes’s shot, it was too late.

That is a great tip especially to those fresh to the blogosphere.

Short but very accurate info… Appreciate your sharing this one.

A must read post!