Our series looking at the US and the World Cup continues with a look at how the US did in the 1950 World Cup.

Our series looking at the US and the World Cup continues with a look at how the US did in the 1950 World Cup.

It is easy to forget that the US played more than one game in the 1950 World Cup in Brazil. Before its historic 1-0 victory over England, the US played four qualifying games against Mexico and Cuba in the lead up to their first match in Brazil against Spain. After the victory over England, the US next faced Chile.

Background to the 1950 World Cup

Because of the Second World War the planned 1942 and 1946 World Cup tournaments did not take place. The US had not entered qualification for the last pre-war World Cup, won by Italy, in France in 1938.

A number of national teams decided not to participate in the 1950 World Cup. Hungary and Russia would not play teams from the West. France refused to enter the competition as a substitute for Turkey. Austria and Hungary thought their teams were not yet ready to play again on the world stage. Argentina, Ecuador and Peru all pulled out of qualification. West Germany had not yet been admitted into FIFA.

None of these absences mattered as much as England’s participation in what would be its first World Cup. England had withdrawn from FIFA in 1928 following a dispute over payment of amateur players and so missed the first three World Cup tournaments. Universally assumed to be the best team in the world, England was the clear favorite to win the tournament.

Thirteen teams, divided into four groups, would appear in the 1950 World Cup. Brazil, Mexico, Yugoslavia and Switzerland were in the first group; England, the US, Chile and Spain were in the second group; Sweden, Italy and Paraguay were in the third group while the fourth group was made up of Uruguay and Bolivia. After group play, the first place team of each group would then advance to a round robin playoff to reach the championship game.

The US international games before the 1950 World Cup

While the US had not appeared in the World Cup since 1934, a US team did play in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, the last pre-war Olympic games, and also in the 1948 London Olympics, the first post war games. In between, the US played a smattering of games against other national team sides, most of which are not considered full internationals, and many of which ended in resounding defeats.

At the 1936 Olympics, the US drew Italy, the team that had defeated them 7-1 two years earlier at the 1934 World Cup and the tournament’s eventual champion. Like the 1934 US World Cup team, the US Olympic team had a distinctly Philadelphian air about it with 1934 World Cup manager Elmer Schroeder returning as the Olympic team manager. Along with Schroeder were nine players from the Philadelphia German-Americans, holders of the 1935-36 National Challenge Cup, known today as the US Open Cup, and winners of the 1934-35 American Soccer League championship. Among the players were Francis Ryan, captain of the 1934 World Cup team and fellow 1934 World Cup veterans Peter Pietras and William Fiedler. With them from the German-Americans were Robert Denton, Fred Stoll, James Crockett, Charles Altemose, George Nemchik (who would later represent the US in the Castillo Najera Cup), and Frank Lutkefedder. Also on the team was Julius Chimielewski of the Trenton Highlanders. Seven of the 11 players who faced Italy in a 2-3-5 formation at the Berlin Poststadion on August 3, 1936 played for the German-Americans: the entire midfield of Crockett, Pietras, and Altemose, and four of the five forwards including Nemchik, Lutkefedder, Fiedler, and Ryan. Garnered by the familiarity that comes from so many of the players having played together for their club team, the US finished the day with a creditable 1-0 loss to an Italy, who would go on to win the tournament.

At the 1937 Pan American Exposition in Dallas, the US was represented by the Trenton Highlanders, the 1937 US Amateur Cup winners. Playing at the Cotton Bowl, the team was defeated 9-1 by Argentina on July 15, and 3-2 by Canada on July 16. Two months later, a select US side that included the German-American’s Nemchik traveled to Mexico City for the Castillo Najera Cup. There they lost to Mexico three times in two weeks, losing 7-2 on September 12, 7-3 on September 19, and 5-1 on September 26.

A “Scottish Touring Team” faced a team of ASL All-Stars on May 21, 1939 (1-1, with the US goal scored by the Philadelphia German-American’s Nemchik), and June 18, 1939 (a 4-2 win for the visitors after extra time, with the German American’s Altemose scoring the second goal for the home team), at the Polo Grounds in New York but only five of the 17 players on the Scottish team had ever played for Scotland and the game is not recorded as a full international.

With the outbreak of the Second World War only three months after the visit of the Scottish team, the US would not play against international opposition for another eight years, greatly limiting the transmission of knowledge and experience gained from the few pre-war international games in which the US had participated. When the US did return to international competition two years after the end of the Second World War, it was represented by an amateur club team from Fall River, Massachusetts. Winners of the 1947 US Open Cup and US Amateur Cup tournaments, Ponta Delgada represented the US at the North American Football Confederation (NAFC) Championship in Cuba in 1947, losing 5-0 to Mexico on July 13 and 5-2 to Cuba on July 20.

Several Ponta Delgada players would be on the US team that traveled to the London Olympics in the summer of 1948. Philadelphia was represented by Walt Bahr and Bennie McLaughlin, both Lighthouse products who played for the Philadelphia Nationals, as well as Swarthmore College’s Rolf Valtin, who would later join the Nationals. The US Olympic team would play together for the first time in a series of warmup games after they arrived in England, drawing 2-2 with Luxembourg, and losing 3-2 to China, before defeating Korea 2-0, and the Royal Air Force team, 4-0.

Once again, the US was drawn to face Italy in the Olympics. Once again, they were outclassed, conceding two first half goals at a rainy Griffin Park in London on August 2, 1948. Down to ten men, including the Nationals’ Bahr and McLaughlin, soon after the start of the second half, the US collapsed, conceding seven more goals to lose 9-0. Their Olympic run may have been over, but their international shellacking was not, and the US team would play two more games in Europe before returning home, losing 11-0 to Norway in Oslo on August 6, and then losing 5-0 to Northern Ireland in Belfast on August 11.

The US finished the year with a series of three games against Israel. Represented by a reunited Olympic squad for the first game in the series, the US won 3-1 at the Polo Grounds on September 26, a scoreline that included a goal from the Nationals’ McLaughlin. The other two games featured US sides made up of a mix of national team players and ASL All-Stars, including a “US All-Stars” team that defeated Israel 4-1 at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park on Oct. 14. The US won the final game 3-2 with a largely New York-based squad that also included Bahr and McLaughlin at Ebbett’s Field on Oct. 17, 1948.

Bahr would also played on the US team that faced Scotland at Triborough Stadium in New York on June 19, 1949. The US lost, 4-0.

The US qualifies for the 1950 World Cup

While the record of the US after the Second World War against international competition was something of a mixed bag, valuable experience was being gained. Perhaps more importantly, a core of players, whether through accident or design, began to emerge that would form the nucleus of the 1950 US World Cup team, players who had played together in a variety of international friendly matches with touring teams from Europe and South America since 1947, as well as at the 1948 Olympics. Tony Cirino writes in US Soccer vs the World that the team “that was called to play the qualifications for the 1950 World Cup was not the usual pickup team but had been built piece by piece over a period of three years.” Among those on the US roster were Philadelphia’s Walt Bahr and Benny McLaughlin, who would play in each of the three qualifiers.

Qualification for the 1950 World Cup took the form of the 1949 NAFC Championship. Four teams — the US, Mexico, Canada, and Cuba — were invited to participate but Canada declined to send a team. The first and second place teams would qualify for the World Cup. All of the games in the tournament would be played at Estadio de los Deportes in Mexico City.

With the first qualifying game scheduled for September 4, 1949 before the start of league play in the US, a lack of match fitness was a real concern for the team. That, combined with the heat and the 7,400 foot altitude of the stadium, were factors in Mexico’s easy 6-0 victory.

In the next qualification match on September 14, the US somewhat redeemed their first loss with a 1-1 draw against Cuba, who had already lost to Mexico, 2-0. Frank Wallace, who played for the Simpkins team in the St. Louis Major League, scored the opening goal in the 25th minute only for Cuba to equalize five minutes later. Still, the US controlled play for much of the game and their fitness was noticeably improved.

The first half of the second match against Mexico on September 18 ended with the home side up 3-0. Mexico scored again almost immediately after the start of the second half. In the 52nd minute, Ponta Delgada’s John Souza scored for the US. The US scored again in the closing seconds of the second half when Ben Wattman of Brooklyn Hakoah found the net but not before Mexico had added another two goals and the game ended with the US losing, 6-2.

A win in the final match against Cuba would put the US in position for a second place finish in the tournament and the final North American qualification spot for the World Cup. In the 15th minute, Walt Bahr opened the scoring with a long shot from outside of the box. In the 23rd minute, Ponta Delgada’s John Souza scored a second goal. Two minutes later Pete Matevich of Chicago Slovak scored. Ten minutes later Matevich scored again. Before the end of the half, Cuba got a goal back after a handball in the box resulted in a penalty kick. In the 48th minute Wallace brought the US total to five goals. Cuba managed to score one more goal before the match ended as a 5-2 victory for the US.

The US had done all it could, but if Cuba could upset Mexico in the final game of the tournament, Cuba would finish in second place and so qualify for the 1950 World Cup. Mexico won an easy 3-0 victory and the US was on its way to Brazil.

The lead up to the 1950 World Cup

To prepare for the World Cup the best players of the American Soccer League were chosen and formed into an Eastern and a Western team. A final tryout match was held in St. Louis that ended in a 3-3 tie. The final team included from the 1949 qualifiers, in addition to Ponta Delgada’s John Souza, and the Philadelphia National’s Walt Bahr and Benny McLaughlin, Harry Keough (St. Louis McMahon), Charlie Colombo, Gino Pariani, Frank Wallace, Frank Borghi (St. Louis Simpkins Ford). McLaughlin had to withdraw from the team when he found he could not get time off from work to travel to Brazil.

Joining these national team veterans were Ed McIlvenny (Philadelphia Nationals), Ed Souza (Ponta Delgada – no relation to John Souza), Joe Maca (Brooklyn Hispano), Joe Gaetjens (New York Brookhattan), Robert Craddock and Nick DiOrio (Pittsburgh’s Castle Shannon), Geoff Combes, Adam Wolanin and Gino Gard (Chicago Vikings) and Robert Annis (St. Louis Simpkins Ford). Penn State’s Bill Jeffrey was selected as coach just two weeks before the tournament when the New York Americans’ Ernö Schwarz declined the position.

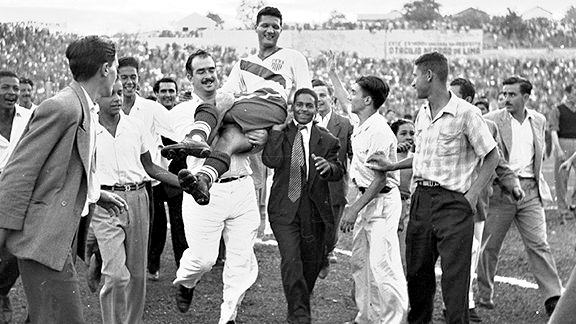

The US team that defeated England at the 1950 World Cup. (back row, l-r) manager Chubby Lyons, Joe Maca, Charlie Colombo, Frank Borghi, Harry Keough, Walt Bahr, coach Bill Jeffrey; (front row, l-r) Frank Wallace, Ed McIlvenny, Gino Pariani, Joe Gaetjens, John Souza, Ed Souza

David Litterer writes in the American Soccer History Archives, “The team was able to get adequate training time, and the players, many part-timers who also held regular jobs, took to the training regimen with gusto.” While many on the team had more experience playing together than had been the case in earlier US World Cup appearances, in one essential respect, things were no from the team that had traveled to the 1934 World Cup. “Most of the players,” Tony Cirino writes in U.S. Soccer vs The World, “even the so-called professionals, were part-timers who played in their off hours and gave up their Sundays for the love of the sport.” The US World Cup team was made up of players who were essentially amateurs.

The day before leaving for Brazil, the US team played the touring All-England team at Randall’s Island in New York. The All-England team had scored 66 goals while allowing only 13 in their previous nine games in Canada. While the US lost, they allowed only one goal. Addressing the US players at a banquet after the match, Stanley Rous, the secretary of the English FA, emphasized how tired the All-England team were after their tour: “When you go to Brazil and play the England national team, then you will find out what football is all about.”

The US versus Spain

On June 25 England began group play at the 1950 World Cup with what was generally viewed as an unconvincing 2-0 victory over Chile. Later that day the US faced Spain at the Estadio Brito in Curitba. Spain immediately took control of the game. In the 18th minute and against the run of play, Pariani scored for the US when he hit a low cross from outside of the penalty area. For the next 60 minutes the US held the lead. Then, in the 80th minute, Charlie Colombo hesitated when he thought the ball had gone out of bounds, allowing a Spanish player to cross. Spain’s Estanislao Basora received the cross for the equalizer. The US defense seemed to collapse after the goal and two minutes later Basora scored a second. Just before the final whistle, Spain scored another to beat the US, 3-1.

Calling the loss a “moral victory,” US goalkeeper Frank Borghi said later, “They were figured to beat us by about eight or nine goals.”

The US versus England

Four days after their defeat to Spain, the US faced England at Estadio Independencia in Belo Horizonte.

The England team had arrived in Belo Horizonte four days before the match. The city had a large community of Englishmen and their families who worked at a nearby gold mine, and the England team were lodged in a hotel with access to a soccer field, a pool, tennis courts, and a golf course, as well as the hospitality of their expatriate countrymen. Four members of the All-England team the US had faced only weeks before, including the legendary Stanley Mortensen, had joined the England squad in Brazil. John Thompson wrote in the Daily Mirror before the match “the only unanswered question seemed to be the size of the American’s defeat.”

The US arrived in Belo Horizonte the day before the match and were unable to practice before the game.

The teams faced each other on June 29 using the same WM formation. England immediately applied pressure and quickly sent a a shot sailing over the crossbar. Cirino writes that, after that goal attempt, the England players “were reported to have ‘strolled back laughing,’ no doubt with visions of all the goals to come.” When those goals failed to materialize, the largely Brazilian spectators enthusiastically supported the US “and the crowd’s excitement grew as they realized that the Americans were creating difficulties for the English.”

In the 37th minute the US scored the most famous goal in the history of the US national team. Ed McIlvenny took a throw-in that found his Philadelphia Nationals teammate Walt Bahr some 35 yards out from the England goal. Bahr advanced the ball some ten yards before unleashing a shot that was headed toward the left side of the goal. Joe Gaetjens met the ball as it dipped in front of the goalmouth, redirecting it with a diving header into the opposite corner past England keeper Bert Williams.

The crowd erupted.

The English were stunned.

England attacked relentlessly for the rest of the game. But with each shot that went high or wide, the England side became increasingly desperate and frustrated. Their best scoring chance came in the 82nd minute when Mortensen was brought down by Colombo. The US keeper Borghi, who was having the game of a lifetime, just managed to clear Jimmy Mullen’s header from the resulting free kick. Late in the game Wallace had a chance to make it two for the US but lost the ball to the keeper.

When the final whistle blew, the crowd stormed the pitch and carried the US players off the field on their shoulders. Joe Maca later recalled, “Some of us went looking for Stanley Rous to remind him of the nice speech at the Waldorf Astoria. He was nowhere to be found.”

While the England players were gracious in defeat to the US, the English press proved to be otherwise. (Only one American reporter, Dent McSkimming, was at the game. A writer for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, he had paid his own way to Brazil.) Some English papers thought that wire service reports of the US vs. England scoreline were in error and that England had won 10-0. They weren’t alone.

When Joe Barriskill, the head of the United States Soccer Football Association (USSFA), received a telegram informing him of the victory he thought it was a mistake.

I couldn’t believe it. When they told me we had won 1-0, I said, “Who the hell you think you’re kidding?” I immediately started to make phone calls. I thought I had lost my mind. I had to telephone England to find out if it was true. And it was true. I could have dropped dead.

Later, various fictions were invented to minimize Gaetjen’s goal. Some reported that the goal was an accident because Gaetjen’s had been trying to get out of the way of Bahr’s shot. Others rather incredibly suggested that Bahr’s shot was a “clearance out of danger.” Bahr said later,

Gaetjens redirected my shot into the other side of the goal, so it wasn’t a case of this ball ricocheting from Joe. Joe beat the defender to the ball and made a great play out of it, changed direction on it and put it on the other side. I have been given credit for the assist. Well, it definitely wasn’t an assist in the truest sense of the word. I took a shot, a good shot, and Joe was the last one to touch the ball and he redirected it into the goal mouth. But I definitely didn’t pass the ball to Joe Gaetjens. I was shooting for the goal.

Some of the lasting questions about the goal, many of which seem to derive from embittered English sources, are no doubt due to the fact that no moving picture footage of it exists. Bahr has said of the different accounts of the goal, “There have been so many varying descriptions of that goal that sometimes I wonder if I played the same game.”

The US versus Chile

On July 2, the US faced Chile in their final game of the group stage at Estadio Ilha do Retiro in Recife. Whereas the game against England had been played in the cool mountains, Recife was one thousand miles away from Belo Horizonte and much closer to the Equator. If the US could beat Chile — and England, who were playing Spain the same day, could secure a win — the US would force a playoff for first place in the group.

It was not to be.

By the end of the first half, Chile was up 2-0 . Surprisingly, the US tied the game in the first five minutes of the second half with goals from Wallace and Maca. After that, the US seemed to wilt in the 110 degree heat. Chile retook the lead four minutes later and never looked back. When the final whistle was blown, the score was 5-2 and the US was out of the World Cup.

After the World Cup

Spain, Uruguay, Brazil and Sweden advanced to the final round robin round of play. Thus far undefeated in the tournament, including a 1-0 win over England, Spain drew 2-2 with Uruguay before being crushed 6-1 by Brazil, while Sweden lost 7-1 to Brazil, and 3-2 to Uruguay, to set up an all South American final. When Brazil and Uruguay met in the final on July 16, 1950, they did so in front of an astounding 200,000 spectators at Estadio do Maracana. After a scoreless first half, Brazil went ahead in the 47th minute. Uruguay then accomplished the improbable with goals in the 66th and 79th minute to win their second World Cup. Brazil would have to wait until the 1958 World Cup in Sweden to win its first.

After the World Cup, largely English sources suggested that the US had illegally fielded foreign players. At first, perhaps because of his name, attention was directed at Gino Pariani. But Pariani had been born and raised in St. Louis. Eventually, attention focused on the three nonnative players, McIlvenny, Gaetjens and Maca, none of whom were US citizens. In fact, Maca had played for Belgium against England in 1945.

But according to the rules of the day, a player had only to declare his intention to acquire citizenship by “filing for their first papers” in order to play for a country in which they were not a citizen. The England FA never filed an official complaint and FIFA cleared the US of any wrongdoing. Only Maca would eventually become a US citizen after playing in his native Belgium for a time. McIlvenny would go to England to join Manchester United while Gaetjens played professional soccer in France before returning to his native Haiti. In 1964, Gaetjens was arrested by “Papa Doc” Duvalier’s secret police. His body was never found.

The rest of the US team returned to their day jobs and club teams. The USSFA failed to capitalize on the sudden popularity of the US team around the world and turned down the many invitations to visit countries who were anxious in seeing the wonder team. The federation did propose a home and away series with England for 1951 and 1952 but the offer was “reluctantly declined” due to scheduling conflicts. On June 8, 1953, the US hosted England in a friendly at Yankee Stadium. Playing for the US team that day were World Cup veterans Bahr and Keough, as well as Benny McLaughlin. The US lost, 6-3.

In 1976 the entire 1950 World Cup squad was inducted into the National Soccer Hall of Fame in a ceremony in Philadelphia.

Fourteen years later, the US would appear in its first World Cup since 1950. It would be another four years until the US won another World Cup game, it’s first since the historic defeat of England 44 years before.

A version of this article was first published on April 29, 2010

This whole series is +1000. Awesome stuff!

Great article! Thanks to share your knowledge with us, amazing!

Thanks, James and OneManWolfpack, there’s plenty more to come.

Hi blogger, i must say you have very interesting content here.

Your page can go viral. You need initial traffic only.

How to get it? Search for: Mertiso’s tips go viral

Wow, what great history! Harry Keough used to talk about this game often while coaching us at St. Louis University to national titles. He introduced us to Mr. Bahr once when in Philly. I remember talking goalkeeping skills and techniques later with Frank Borghi in later years. A thrill I will never forget! Entertained Frank with story of him arriving late to St. Louis league softball games with Charlie Columbo as anxiously awaiting manager. I was nine at the time. Charlie Columbo did not like little kids. Nor did he like anyone on the other team while playing.

I played against the Charlie Columbo coached team, St. Ambrose in 1965. This was a week before they were to travel to Philly for the National Amateur Final. Our team was Kutis Jr. and we were only a first year junior team for the most part. Columbo challenged us to a practice game. Most of us were only 16. All of our players wanted to play them except me, the goalkeeper. Well we had a scrappy and fast team. Many of us from north side parish Our Lady of Perpetual Help. i had grown up with most of them. To the astonishment of all there, we held them to 0-0 thru 3/4 of the game. Much of the action was on our end and their pressure was considerable. I as the gk had plenty to do. I had a number of good saves and our guys fought like devils to hold them off. Columbo was not happy. Even to the point of verbally abusing me, a 16 yr. old kid as the action progressed. I gave it right back to him, and my father who was there, glared at him. Obviously he was trying to throw me off my game. This verbal abuse was part of his normal behavior that he was known for. So in later years I took this as a badge of honor to be yelled at by him. Our team manager put in the number two gk, and St. Ambrose scored two easily. But i knew at the time, that if they couldn’t easily handle a group of scrappy 16 year olds, that they would get their clocked cleaned in Philly. And they did loosing 6-0 to the Philly German Hungarians. But that game was a turning point in my soccer career. I thought after that that i could excel somewhat in this game. In two years I was recruited by St. Louis University and was subsequently in goal for the undefeated SLU NCAA Championship teams of 1969 and 1970, playing for the legendary Harry Keough.

Charlie Columbo was quite a softball player and pitcher. He had a fine moving riseball and an excellent change up. Very consistent hitter. He was one of the fastest players i have ever seen on a softball field. And i have been viewing world class softball for over 60 years. He could lay down a perfect bunt and get to first in an absolute flash.

He challenged the perennial national power Aurora Sealmasters to a game in St. Louis in the late 50’s. Aurora had won at least one national title and contended every year as one of the top teams in the USA. Aurora was in St. Louis to play midwest power team coached by Norb Thurmer. As the story goes Aurora played games on Saturday and decided to stay the night and wanted another game Sunday AM. Columba’s “bar team”, Wilmar Lounge took them on and shockingly defeated the renown Sealmasters. Although I did not witness the game, it was the talk of the softball community from north to south St. Louis. I am telling you that was almost as great a feat as the 1950 USA WorldC up defeat of England that Charley was such a big part of. Charlie Columbo was a winner in the truest sense of the word.