Featured image: Bert Patenaude (in white) at the 1930 World Cup

With the holidays rapidly approaching, soon we will see the end of the United States Soccer Federation’s Centenntial Year. To commemorate its 100th birthday, the USSF recently issued its All-Time Best XI, honoring the best footballers who have ever donned a U.S. kit.

These lists are always subjective, at best, and — frankly — are designed to generate debate. Nevertheless, the Best XI — consisting entirely of players who suited up for the U.S. in the past quarter century — left a lot of people scratching their heads. Sure, the MLS-era has helped produce a pool of players deeper than the U.S. has enjoyed at any point in its history. Yes, international teams play many more games in the modern era, giving post-1990 players many more opportunities to shine. But, seriously — no one from before 1990? No consideration of the U.S. team that finished in third place in the inaugural World Cup of 1930? No one from the 1950 team that stunned England in the Greatest World Cup Upset Ever? Not a single player from the NASL generation that labored hard to the set the table for today’s domestic success?

Nonsense.

Now, before we get carried away, the fact is the well-credentialed members of the voting committee got most of it right. Stated simply, the post-1990 era is the best documented for U.S. international soccer, and the committee could make judgments based on memory and actual evidence (e.g., game footage), and obviously did not rely too heavily upon anecdotal evidence provided from the breathless news reports of the 1920-30s era and the memories of ex-players whose feats may have been exaggerated by the passage of time. (As Shep Messing once told me, “The older I get, the better I was!”). By and large, the USSF’s Best XI is the best this country has produced.

Still, just because something is not on film does not mean it did not happen. Over the first 75 years of the USSF’s existence a number of great players played for the U.S. — a few of whom could have easily starred on today’s squad — and all of whom are worthy of recognition. Thus, even if anecdotes and game reports are our only source, an alternative USSF’s Best XI is worthy of discussion. Let’s call it the Dodranscentennial Best XI, with the focus on players from the pre-MLS (actually, pre-1990) era.

In making my choices, I’ll largely use the same criteria employed by the USSF:

- Starter or key contributor to overall success on the field, especially in World Cups

- Longevity, overall performance and talent on the field with the U.S. Men’s National Team

- Impact on the legacy of the U.S. Men’s National Team program

I am going to deviate from these criteria somewhat — given how infrequently the U.S. team played in the pre-1990 era, I will also take into account Olympic play and Pan-American Games.

Also, in deference to the soccer of the era in question, I will be naming a 3-3-4 team — the 1920s and 30s saw use of the W-M, while by the 1970s we saw 3-4-3, so the 3-3-4 is a bit of a compromise.

All set? Then here we go:

GOALKEEPER

Arnie Mausser (1975-1985) — 35 caps

Yes, Frank Borghi stood on his head in 1950 in the upset win over England … Sure, Shep Messing made about 72 saves in a 7-nil loss to West Germany in the 1972 Olympics … Probably, had he not been crippled by a thuggish Argentine in the 1930 semifinals, Jimmy Douglas could have led the U.S. to World Cup glory.

Still and all, the nod at this deepest of U.S. positions has to go to Mausser, who is the most-capped goalkeeper of the pre-1990 era. The 6’5” Brooklyn native posted 10 clean sheets during his tenure, and was the most consistent selection in an era that featured Messing, Bob Rigby, Winston DuBose, Alan Mayer, and David Brcic.

Alas, to the extent he is remembered at all today, it is for a blunder: in 1985, the U.S. was a tie away from going to the second round of qualifying for the 1986 World Cup. In the final match of the round against Costa Rica, Mausser weakly punched away a cross he could have caught; the ball fell to the feet of Evaristo Coronado who easily scored the goal which eliminated the U.S. from the World Cup contention and sent Costa Rica to the second round instead.

Mausser was voted into the U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame in 2003.

DEFENDERS

Harry Keough (1949-1957) —17 caps;

Bobby Smith (1973-1980) — 19 caps;

George Moorhouse (1926-1934) — 7 caps

The U.S. backline features three players from the three main eras of the USSF’s first 75 years.

The Liverpool-born Moorhouse emigrated to Canada in 1923, and soon signed with the New York Giants of the American Soccer League. The bruising left back was first capped in 1926 versus Canada, and Moorhouse was named to the inaugural U.S. World Cup team, playing in all three matches in 1930. He was later named captain of the 1934 World Cup team. Moorhouse entered the U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame in 1986.

Keough was a legendary defender in the St. Louis leagues throughout the 1940s and 1950s, and the Mound City native earned a number of U.S. caps in that period. Robin to Borghi’s Batman in the 1950 match versus England, Keough was instrumental in preserving the victory, providing a number of crucial tackles late in the match, and he also starred in the Americans’ gutsy opening match loss to Spain in that tourney. While he was used as a midfielder many times throughout his national team career (scoring his lone U.S. goal from that position in 1957 against Canada), his titanic 1950 performance puts him on the backline here. Elected to the U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame in 1976.

Trenton, NJ-native Smith was a frequent selection during the NASL-era. His first cap was earned in one of the biggest upsets in U.S. history, the now-forgotten 1-0 victory over a powerful Poland squad in 1973. Smith’s style was rarely pretty, but his rugged defending helped keep the U.S. competitive in games where they should have been blown out—the Poland match, a 1-nil loss to Mexico in 1974, and others. Then again, Smith was also on the field for Poland’s 7-nil revenge at home in 1975, and Italy’s 10-nil thumping of the red, white, and blue in Rome two weeks later. Smitty was elected to the U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame in 2007.

MIDFIELDERS

Billy Gonsalves (1930-1934) —6 caps

Walter Bahr (1948-1957) — 19 caps

Ricky Davis (1977-1989) — 35 caps

Once again, we find our selections neatly straddling the three eras.

Gonsalves should need no introduction … but, alas, he does. Unquestionably the greatest U.S. born soccer player ever prior to the arrival of Landon Donovan, Rhode Island-native Gonsalves was a giant of a man, known equally for his accurate passing and cannon of a shot. Over the winter we will likely publish a full-length article on the man and his accomplishments. Here, we’ll just stick to calling him the Greatest U.S. Player Of The 20th Century — and one of the few on this list who deserves a spot on the 100th Anniversary Best XI. Not surprisingly, Gonsalves was a member of the inaugural class of the U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame in 1950.

Kensington-native Bahr appeared for the U.S. National Team for almost ten years, invariably captaining the squad. Best known for his assist on the goal which beat England in 1950, Bahr scored one goal in his national team career, against Cuba during 1950 World Cup qualifying. Bahr entered the U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame in 1976.

Denver-born, California-raised Davis had a tenure with the national team that can only be described as snake bit. Davis first made a name for himself when he left college early to sign with the mighty New York Cosmos. His reputation grew during the 1977 U-20 World Championships, where he netted 8 goals for a team that went 5-2, but failed to qualify for the finals. Davis was slated to lead the 1980 Olympic team before President Jimmy Carter’s boycott of the Soviet-hosted event ended its participation. Davis played for the U.S. in the 1984 Olympics, where he scored two goals in the U.S. victory over Costa Rica. That year also saw him named the U.S. Soccer Athlete of the Year, the first year of the award. Davis played again at the 1988 Summer Olympics, and he was named captain of the squad. Davis was looking forward to the 1990 World Cup qualifying games in 1989, but suffered a serious knee injury in January 1989. Although he tried to work himself back into shape in order to make the World Cup roster, U.S. coach Bob Gansler never called him back to the team — a move seriously questioned at the time, as his experience would have surely aided a team of overmatched college kids. Overall, he earned 36 caps (a record at the time), scoring seven goals. Davis was elected to the U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame in 2001.

FORWARDS

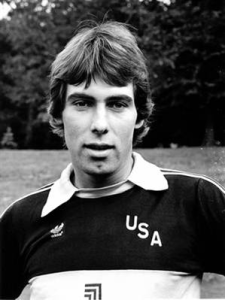

Bert Patenaude (1930) — 4 caps

Bruce Murray (1985-1993) — 85 caps

Ruben Mendoza (1952-1959) — 4 caps

John Souza (1947-1952) — 12 caps

Patenaude only played in one World Cup, but his impact remains today. The Fall River-native featured prominently in the 1930 side, scoring two goals against Brazil in a 4-3 loss in a pre-tournament friendly and then adding one goal in the team’s opening match against Belgium. Patenaude is best remembered today for his performance in the next game against Paraguay, where he scored the first World Cup hat trick. Patenaude’s record of four goals in one World Cup remains the standard for an American player, and this total stood as the all-time career mark for an American player for eighty years, until it was broken by Landon Donovan during the 2010 finals. Patenaude entered the U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame in 1971.

Although Murray’s career drifted a bit into the post-1990 era, he was a fixture for the national team in those awkward years when no Division One soccer existed in the U.S. The Maryland native had an outstanding college career at Clemson, winning the Hermann Trophy in 1987. He was already two years into his national team career by then, earning his first cap in 1985 against England. One of the more experienced members of the 1990 World Cup team, Murray scored a goal and an assist in his three games. Concussions ended his career prematurely, but not before he became the first U.S. player to earn 100 caps. Murray entered the U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame in 2011.

The next two selections come from that least-documented era of U.S. soccer—the 1950s. The criminally-forgotten Mendoza was born in St. Louis, and moved to Mexico when he was eight. Returning to the U.S. when he was 16, Mendoza quickly made a name for himself in the competitive St. Louis leagues. Only 19 when the U.S. was selecting the 1950 squad, Mendoza’s youth may have cost him an opportunity at being a part of history. “Kind of a small kid, and young,” said Harry Keough in Geoffrey Douglas’ The Game Of Their Lives, a recounting of the upset win over England, “but real skilled for his age—for any age. A heck of a player. Three years later, he made the national team.” Given the relative lethargy of the U.S. National Team program in the era (along with the fact that soccer was a semi-professional prospect, at best, and many players eschewed national team duty because of work commitments), Mendoza was only capped 4 times—but he scored two goals in his appearances, both in World Cup qualifying. He also appeared for the 1952 Olympic team. Shockingly, Mendoza is the only person in this Best XI not in the U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame.

“Clarkie” Souza was a Fall River native, and one of the smoothest forwards to ever don a U.S. kit. Earning his first cap against Mexico in 1947, Souza then represented the U.S. in the Olympics in London in 1948 before returning to the national team later that year. So brilliant was Souza’s performance in the 1950 World Cup that England manager Walter Winterbottom hailed him as the best player on the squad. Indeed, Souza was considered by many to be the best inside forward to have competed in the entire tournament, and he was named to the World Cup All-Star team, the only American to be so honored until Claudio Reyna in 2002. Souza entered the U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame in 1976. Along with Mausser, Keough, Bahr, Patenaude, Murray and Gonsalves, Souza was at least on the ballot for the 100th Anniversary team. Alas, he did not receive a single vote (perhaps his inexplicable listing as a midfielder contributed to that).

—•—

This being the PHILLY soccer page, it should be noted that — in keeping with the city’s significant contributions to American soccer over the past 100 years — a number of these players have Philadelphia connections. Bahr was born in Philadelphia, played for a number of area club teams, and coached at Temple; Smith was born in nearby Trenton, and starred with the Philadelphia Atoms, Fury and Fever; Patenaude’s professional career began and ended with Philadelphia clubs; and Souza died in Dover, Pennsylvania, in York County.

—•—

So there you have it — the USSF Dodranscentennial Best XI.

Should any of these players have been on the 100th Anniversary team? Gonsalves certainly (to the Committee’s credit, he was not forgotten, finishing fourth on the forwards list); Bahr probably (again, not forgotten — the Committee gave him the highest number of votes for a pre-1990 midfielders); Davis and Souza possibly. The fact that the U.S. team was, by and large, a usually overmatched group of semi-pros most of the time makes it difficult to truly evaluate how good these guys were compared to the players of the modern era.

Nevertheless, these men deserve to be remembered for what they were: the best the U.S. had to offer in the days before MLS.

Thank you for the wonderful write-up about my late husband, Ruben Mendoza. He lived and breathed soccer and hundreds, if not thousands of kids here in the Metro-East (Illinois) area of St. Louis now play soccer, thanks to his introduction of it in league play and his convincing of the area high schools to offer it as a sport. He also convinced them to have girls’ teams a bit later. By the way, he was also on the 1956 U.S. Olympic team and on the 1960 team that did not qualify to go to the Olympics. Our Granite City High School soccer teams won 7 state tournaments in a row with boys that he had coached in their younger competitions. Look up the Illinois State Soccer Tournaments to learn just how many more they won–so many that others began to call the state tournament the Granite City Invitational. Please excuse my bragging, just have to be proud of his legacy.