By 1916, exhibition soccer games on Christmas Day were a Philadelphia tradition that dated back at least to the inaugural season of the city’s first organized league, the Pennsylvania Football Union, in 1889. As was the case then, the exhibition game in 1916 took place at the grounds of one of Philadelphia’s professional baseball teams, this time at the Phillies Ball Park. Located on a small city block in North Philadelphia bounded by North Broad Street, West Huntingdon Street, North 15th Street, and West Lehigh Avenue, the stadium would later be best known as the Baker Bowl.

The day’s event was actually a double header, with both games being played over shortened halves. That the games were played at all was something of a miracle. The Inquirer reported on Dec. 24 that the Saturday game scheduled to take place at the Phillies grounds the previous day had been postponed because “one end of the ground was covered with a layer of ice.”

The first game featured the John R. Foster team against Martex Towel Company, both members of the recently formed Industrial League. It was a dreary 1–0 match of “kick and rush style of play with little judgement used by the players.” The match report in the Dec. 26, 1916 edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer noted, “Attempts at passing the ball were spasmodical and quite a few of the spectators seemed relieved when Referee Ward tooted the whistle ending the agony, with the Foster team being entitled to the spoils, what little there was in it.”

The main event proved much more entertaining and featured Standard Rollers, also of the Industrial League, against long-standing local powerhouse, Philadelphia Hibernians of the American League. The Inquirer’s match report said, “With the grounds in fast condition, considering the recent elements, play in consequence was of a thrilling character at times, with the Hibs having the measure of their inexperienced opponents right from the start.” Hibernian finished the game 4–1 winners.

But the big game for area soccer fans that day was taking place 900 miles away in St. Louis. There, Bethlehem Steel FC were playing the Ben Millers for the bragging rights of unofficial champion of the United States.

National champions

That Bethlehem Steel were already the official champions of the US was not in doubt. In May of 1916, the team had won their second consecutive United States Football Association’s National Challenge Cup (now known as the US Open Cup) and in June they won their second American Football Association’s American Cup. In doing so they became the first team to win both competitions in the same year, a feat they would go on to repeat two more times.

In doing so they became the first team to win both competitions in the same year, a feat they would go on to repeat two more times.

Still, the claim that these tournaments represented national championships was, with justification, in dispute by some. While the American Cup tournament had been founded in 1885, the entrants for the 1915-16 season all hailed from Southern New England, Eastern New York, Northern New Jersey and Eastern Pennsylvania. The National Challenge Cup, founded in the 1913-14 season, featured teams from as far west as Detroit and Chicago in 1916 but most of the competing teams came from the same areas as those in the American Cup.

And the St. Louis soccer community knew it.

The St. Louis scene

St. Louis had its first organized league in 1886 and, as was also the case in Philadelphia, many of its early teams were neighborhood or parish-based. Two of the three teams that participated in the exhibition soccer games 1904 Olympics in St. Louis were local teams. The tours of the Pilgrims team from England in 1905 and 1909, so important to the development of soccer in the US, had been organized by two St. Louis soccer enthusiasts, Thomas Cahill and Winton Barker. In 1907 the city was the location of the only fully professional league in the US.

By 1910, St. Louis had grown to be the country’s fourth-largest city. Thomas Cahill moved that year to Newark, New Jersey, where the headquarters of the American Football Association was located, and began the work that led to the founding of the United States Football Association, known today as the US Soccer Federation. St. Louis soccer had by now gained a national reputation and in 1911, Philadelphia’s Tacony FC, winners of the 1910 American Cup, traveled there to play the city’s St. Leo’s team to a 4–4 draw.

By 1915, the wages of professional players in England had been capped at £4 per week, or $337 in 2011 dollars. David Lange writes in his excellent Soccer Made in St. Louis that players in the professional St. Louis League, which would be the best league outside of the Northeastern US for the next 20 years, were earning as much as $7 apiece per game (or $154 in 2011 dollars) in 1915. Not too bad for a professional league based in a single city. Bethlehem Steel was, at this time, an amateur club. The 1916-17 Spalding Guide noted, “The players receive no remuneration for playing, however; they all occupy good positions in the steel plant and are given time to practice and make the long trips which are necessary in the various cup competitions.”

Negotiations for Bethlehem Steel to travel to St. Louis during the 1915-16 season had failed over disagreements about financial guarantees. Following Bethlehem’s Cup winning double in the spring of 1916, the necessary guarantees were made: Bethlehem Steel would play two exhibition games over the Christmas holiday in St. Louis.

First stop: Chicago

On Thursday, December 21, 1916, 18 Bethlehem Steel team players, a trainer, and business manager Harry W. Trend left South Bethlehem by train for Chicago. They arrived in a snow covered Windy City the next day for light training at Comiskey Park before a night of rest at the Great Northern Hotel. On December 23, they faced a Chicago All-Star team in what the match report in the Philadelphia Inquirer the next day called “one of the hardest fought soccer football games seen in Chicago in years.” Five of the players on the Chicago team were members of the Pullman FC team, the December 23 edition of the Inquirer had noted, and would have “had the benefit of two games against the national champions” in National Challenge Cup play earlier in the year. In the semifinals of the Cup that April, Pullman and Bethlehem had first played to a scoreless draw before Bethlehem prevailed in the second game, 2–1. The Inquirer reported that “The Chicago dopesters figure that on the snow surface the speed of the Chicago players will offset the combination play of the visitors.”

The Chicago team did come out fast against the visitors with both sides playing the standard 2–3–5 formation of the day. The home team scored in the first half before Bethlehem’s “superior conditioning favored them in the second half, when they fairly ran over the locals and scored the points that gave them the victory.” Final score: Chicago 1–2 Bethlehem. The South Bethlehem newspaper The Globe had reported on December 20 that Bethlehem would leave Chicago immediately after the game. They had to—the next day they would face the St. Louis All-Stars.

In St. Louis

Bethlehem arrived in St. Louis with a 19-game unbeaten record. There they would first play a picked team on Christmas Eve comprised of all-stars from the St. Leo’s, Innisfalls and Naval Reserves teams before then playing the Ben Millers, the other team in the professional St. Louis league on Christmas. Where as Charles Schwab, the owner of the Bethlehem Steel Company, searched as far as as England and Scotland for players for the Bethlehem Steel team, the St. Louis teams featured native-born players. Lange writes, “The experts back East believed Bethlehem Steel and the other top teams from that region, all of them relying heavily on foreign players, were the class of US soccer. Many St. Louisans felt otherwise.”

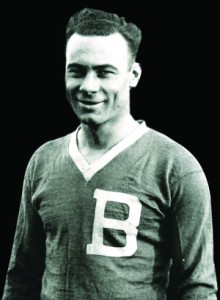

In front of some 7,000 spectators, “the largest crowd that has seen a soccer exhibition here since the invasion of the Pilgrims,” Bethlehem got off to a quick start, scoring after the first minute of play to finish the half leading the game, 1–0. The goalscorer was Harry Ratican, a player from St. Louis that the Bethlehem team had signed after learning about him during negotiations for the aborted 1915 visit. The Inquirer reported on December 25, “In front, Bethlehem played a wonderful game. Their passing was excellent, favoring the short shots instead of the long boots. St. Louis was dazed and stunned with that first goal. They were timid and shy.”

Not so in the second half.

Re-arranging their front five, and displaying a new aggressiveness, The Globe reported on December 26 that St. Louis now “played whirlwind but systematic football and the visitors were swept off their feet by the fierce attack.” The Inquirer said of the All-Stars in the second half, “They bunched around in groups and turned their attack around completely.” A series of scrimmages in front of the Bethlehem goal soon resulted in two goals for the home team, the second goal being loudly protested by the visitors. Lest there be any doubt, St. Louis would record a third goal before the final whistle. The Inquirer concluded that “the local athletes simply wore down their opponents.”

The result could have been very different. At one point in the first half a St. Louis player player had to leave the game with a knee injury. “An exhibition of sportsmanship was displayed by the Bethlehems,” wrote the Inquirer. “Soccer rules prevent the allowance of a substitute, but Bethlehem permitted another player” to enter the game.

Against the Ben Millers

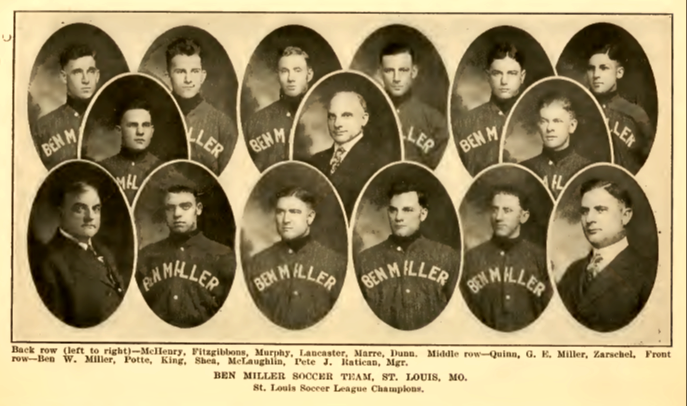

The next day in front of some 6,000 spectators on Christmas, Bethlehem faced the Ben Millers, a team sponsored by a local hat company. The Inquirer described the match in their match report on December 26 as “A slam-bang battle in which skinned shins, bruised knees and black eyes predominated…The two teams played toe to toe: they roughed it up and they mixed it. Fouls were numerous…”

Ratican again opened the scoring for Bethlehem, heading a goal in the middle of the first half. Then, a minute before the end of the half, a penalty was committed against a Ben Millers player in the box. They made no mistake with the penalty kick to draw level, 1–1.

The second half opened up with the home team controlling play in front of the Bethlehem goal. Soon, shot was stopped by the Bethlehem keeper but he bobbled the ball while trying to carry it out for a clearance. The Ben Millers pounced on the error and scored to take the lead. Holding the lead almost to the final whistle, the Ben Millers keeper slipped in the closing minutes of the match while attempting to cover a shot, thus allowing a Bethlehem goal. Final score: Ben Millers 2–2 Bethlehem Steel.

As had been the case in the previous game, the result could have been very different. During the scoring of the second Ben Millers goal, the Bethlehem keeper was kicked in the stomach and had to leave the game. While Bethlehem manager Harry W. Trend had agreed before the start of the game that no substitutes would be allowed, the Ben Millers insisted that one come on to replace the injured keeper.

The South Bethlehem newspaper The Globe concluded in their December 26 match report, “St. Louis now has a legitimate claim to premier ranking in soccer having taken the series with the champion. You might even go so far as to credit six of the seven goals to St. Louis, for Harry Ratican, a local product, counted two of the Bethlehem markers. Take it any way you wish, you must award the crown to St. Louis.” The Inquirer reported, “Manager Trend, eager to strengthen the Bethlehem Eleven, expects to sign three local players within a week.”

Revenge

On March 26, 1917, the Globe reported that negotiations were underway for the Ben Millers to play in Bethlehem in the first game of a three-city tour that would be followed by games in New York and in Philadelphia. “The local management has been after the St. Louis Soccer league for quite a while,” the Globe reported, “and it will be interesting to see how the Western Champions will size up when playing under the rules of the United States Football Association with neutral referee and linesmen.”

When the Ben Millers faced Bethlehem on April 7 on a cold and windy day in front of some 2,500 spectators at Bethlehem Steel Athletic Field, they were easily outclassed. “A gale sweeping over the field made long shots impossible,” the April 8 edition of the Inquirer reported. “Due to the wind Bethlehem resorted to a short passing game in which they displayed vast superiority over the Missourians. The later are used to a long passing game and this style proved entirely ineffective.”

Playing with the wind and the sun at their back after winning the toss, Bethlehem opened the scoring 12 minutes after the start “on a long high kick…the ball was lost in the sun and no attempt was made to stop it.” Soon after, Bethlehem was fouled in the box on another attack and converted to make it 2–0. The match was a chippy affair with the Ben Millers committing 22 fouls to Bethlehem’s 15. Bethlehem recorded nine corner kicks to the visitor’s one and the Ben Millers single decent chance on goal from open play wouldn’t come until the second half.

Playing with the wind and the sun at their back after winning the toss, Bethlehem opened the scoring 12 minutes after the start “on a long high kick…the ball was lost in the sun and no attempt was made to stop it.” Soon after, Bethlehem was fouled in the box on another attack and converted to make it 2–0. The match was a chippy affair with the Ben Millers committing 22 fouls to Bethlehem’s 15. Bethlehem recorded nine corner kicks to the visitor’s one and the Ben Millers single decent chance on goal from open play wouldn’t come until the second half.

Any thoughts that may have lingered in the Ben Millers minds about the superiority of St. Louis soccer were further diminished when they were defeated 3–2 by New York FC the next day. On April 9, the Ben Millers traveled to Philadelphia to play Tacony’s Disston team, champions of the city’s American League. The Inquirer reported on April 10, “There was no doubting the superiority of the Taconyites, who gave one of their best displays, notwithstanding that the ground was slow and heavy from the snow.” Disston scored first in the 38th minute and from there they never gave up the lead, winning 3–1. While the previous matches between Bethlehem and St. Louis teams had been characterized by rough play,the match in Philadelphia was different. The Inquirer match report noted, “Too much credit cannot be given to both teams for the clean sporting instinct in which they played the game.”

Aftermath

Six days after Bethlehem’s win over the Ben Millers, Harry W. Trend died from pneumonia, contracted at the exhibition game. He was 35-years-old and left behind a widow and two young sons. In his eulogy for Trend in the 1917-18 Spalding Guide, Thomas Cahill wrote, “Not in years has the great winter game lost so widely popular and so valuable a friend…Mr. Trend died a martyr to soccer, the game to which he gave unselfishly the major part of his time and effort.”

Bethlehem would lose 1–0 to Fall River Rovers, the team they had defeated for the championship the year before, in the National Challenge Cup final on May 5, 1917. Fall River advanced to the final after they defeated Disston in a semifinal that went over two legs. On May 7, Bethlehem defeated West Hudson AA 7–0 to win the American Cup championship for the second year in a row. They would win the American Cup, and the National Challenge Cup, again in 1918 and 1919.

Harry Ratican remained with Bethlehem Steel through 1919, and was with the team for their Scandinavian tour of that year, before returning to St. Louis to play with the Ben Millers in 1923. He scored two goals in his debut. He finished his soccer career as a coach in St. Louis.

The season review in the 1917-18 edition of the Spalding Guide said of the Ben Millers tour of the East, “The Ben Millers lost considerable prestige at the close of the season by their tour of the East. To begin with, the club had nothing to gain with the trip and everything to lose.”

An article in the April 9, 1917 edition of the Inquirer described the Ben Millers’ plans to tour Sweden that summer. But those plans were already doomed. On April 6 the US had declared war on Germany to enter World War One and the tour proved impossible. It would not be until after the war in 1920 that the Scandinavian tour would take place, the same year that St. Louis teams entered the National Challenge Cup competition for the first time to make a legitimate claim at being champions of the US, the Ben Millers among them. The opportunity was not squandered: on May 9, 1920 the Ben Millers defeated Fore River in the final 2–1. St. Louis teams would appear in the Cup final five out of the next six years, winning the championship once.

Bethlehem Steel would meet the Ben Millers in the final of the 1925-26 National Challenge Cup at Ebbetts Field in Brooklyn, winning the Cup for the fifth and final time in their history on April 11, 1926 in convincing fashion, emphatically defeating the St. Louis side 7–2.

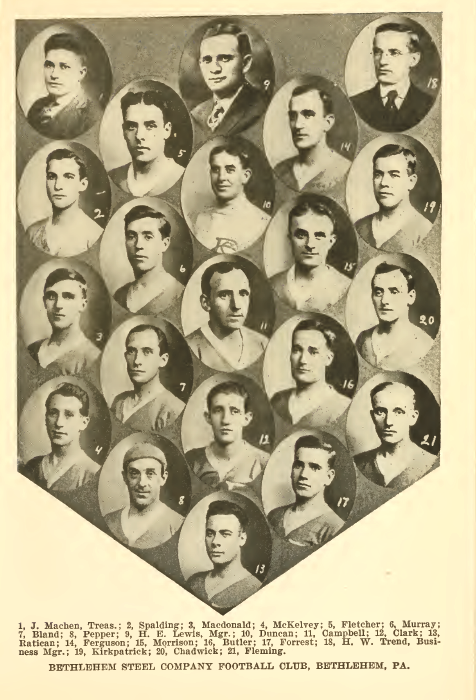

Photo of Harry Ratican from David Lange’s Soccer Made in St. Louis. All others from the 1917-18 Spalding Guide. Go to http://bethlehemsteelsoccer.org/ for more about Bethlehem Steel FC.

Fantastic history here, Ed, thank you! 🙂

Thank you, Joseph, I’m glad you liked it. I love this stuff!

All I want for christmas is one of those sweet bethlehem steel kits!

Really good stuff. Thanks for taking the time to put it all together.

I do have one slight correction, though. According to the American Soccer History Archives (http://homepages.sover.net/~spectrum/year/1926.html), the match between Bethlehem Steel and J&P Coats a semifinal and Bethlehem went on to beat Ben Millers in the final 7-2.

Again, though, great stuff.