Photo: Detail of Philadelphia Inquirer headline from October 20, 1901

After winning the American Cup on May 22, 1897, Philadelphia’s Manz team played a game at the “International sporting carnival” that opened the summer season at Washington Park on the Delaware. To reach the park, boats left regularly from the Arch Street and South Street wharfs carrying passengers round-trip for 15¢, with children riding for free. In August, Manz also played an All-Philadelphia team at the city’s Caledonian games in a short contest consisting of two 15 minute halves. After 30 minutes of play, the game ended as a 1-1 draw. After that, the Manz team disappears from the pages of Philadelphia’s newspapers.

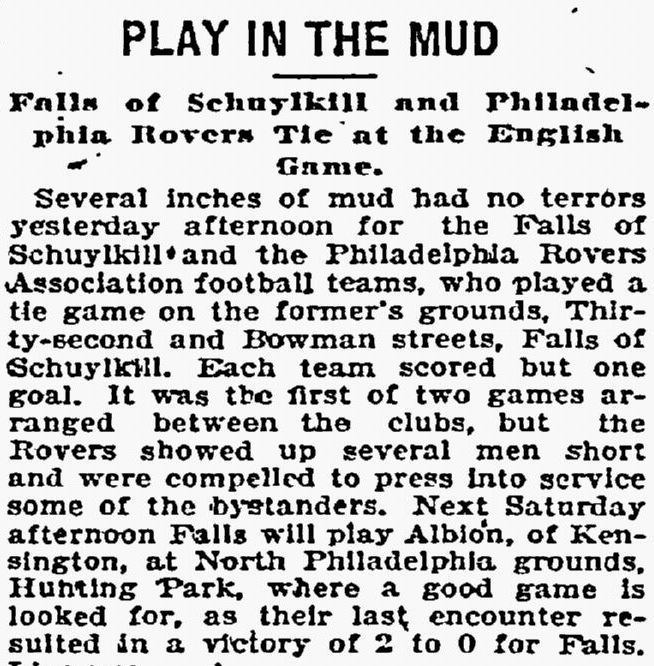

Indeed, newspaper accounts of soccer games in Philadelphia remained sporadic through much of 1898 — continuing a marked decline in coverage that, as was discussed earlier, began in 1895 — with occasional reports involving teams such as Falls of Schuylkill, Philadelphia Rovers, Albion, Kensington, Eddystone, Wax End, the Old Philadelphia Association team (perhaps connected to Beecroft’s Philadelphia Association team or Manz), and the Brill team. Reports also mention intercity games between Albion and the Jersey Blues team of Trenton. In Philadelphia on New Year’s Day, 1898, the teams drew 2-2, the same scoreline at the final whistle when the teams met again in Trenton on February 6.

League soccer in Philadelphia at the close of the 1890s

Whether these teams belonged to an organized league is unclear. After the apparent demise of the city’s first organized league, the Pennsylvania Association Football Union (PAFU), in 1895, mentions of a Philadelphia soccer league are nonexistent until a reference in Inquirer report on October 10, 1896 that describes the Richmond and Frankford teams as belonging to “the League of Association Football Players.”A report on October 25, 1896 describes a game between Manz and the Richmond teams “of the Association Football League,” as does another report on November 22, 1896 on a game between Manz and Wax End. (A report in the Philadelphia Times on January 28, 1897 on a benefit game for an injured player describes Wax End as the “champion of Frankford.” How they became the champions is not described.) Assuming that Manz’s local opponents belonged to the league, member clubs in addition to Richmond and Wax End included Albion, Frankford, Falls of Schuylkill, Norristown, and Alma. References are also made to other games featuring Tacony, Germantown Rovers, and Cressono during this time.

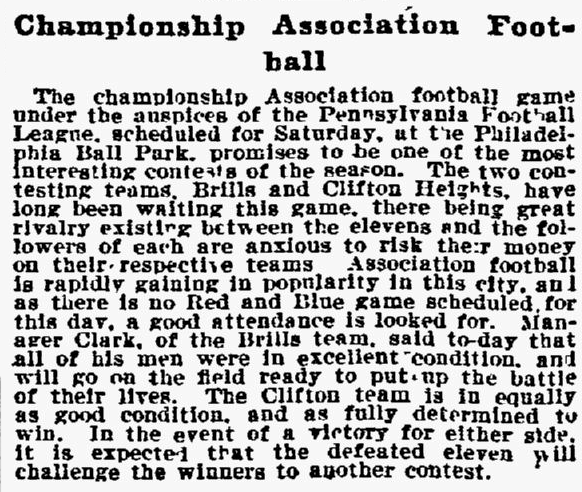

The fall of 1898 saw new mentions of a Philadelphia league. On October 22, 1898, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported the first game of the Pennsylvania Association Football League season, featuring the Brill and Albion teams, at Philadelphia Ball Park. Whether this was a new league or the continuation of “the League of Association Football Players” or “the Association Football League” is unfortunately not clear.

On December 11, the Inquirer, now referring to the league as the Philadelphia Association Football League, published a league table showing six clubs: Albion (from Kensington), Brill (from West Philadelphia at 62nd Street and Woodland Avenue), Clifton Heights, Eddystone, Falls of of Schuylkill, and Norristown. (The Philadelphia Times referred to the league as the “Philadelphia Foot-ball League” on October 30 while a Times report on November 19 referred to it as “the Pennsylvania League.”)

A preview in the Inquirer on November 18 for a match between Brill and Clifton Heights described the teams “have long been waiting this game, there being great rivalry existing between the elevens and the followers of each are anxious to risk their money on their respective teams.” The report also described, “Association football is rapidly gaining in popularity in this city, and as there is no Red and Blue [e.g. Penn’s American football team] game scheduled for this day, a good attendance is looked for.”

While information on the league is scarce, it appears most games were staged at Philadelphia Ball Park at the cost of 25¢ per ticket, underscoring once again the connection between baseball and soccer in Philadelphia as baseball park owners looked to earn income from otherwise empty grounds during baseball’s offseason. Reports also suggest that only one game took place per Saturday, which may have been an effort to maximize attendance at Philadelphia Ball Park or simply a reflection of a decline in the number of local teams sufficiently well organized to commit to a season schedule. Just how far the season carried into 1899 is also unclear, but on April 2, a notice appeared in the Inquirer stating that the Brill team was looking to “arrange a few games on their home grounds.” This suggest either the league season was over, or the league itself had disbanded. The almost complete absence of reports on soccer games taking place in Philadelphia during the fall of 1899, and the total absence of any reference to a league in the few reports that can be found, suggests, but does not confirm, the latter.

Slow growth

Nevertheless, the Inquirer ran an article on December 18, 1899 under the headline “Association Game Grows in Favor.” Describing that association football — or soccer — “is receiving more attention this year than ever before,” the report explained, “This is probably due to the fact that the rules of the game are now better understood than formerly.”

There are many people who do not favor [American] football owing to the number of accidents which annually occur, but now that more clubs are following the rules of the Association game, more favor is bestowed upon it, and more interest taken in the game. By degrees it is making its progress, and though rather slowly, it is hoped, in time, to have a national reputation. At the colleges and universities interest is beginning to be taken in it, and there are some players who prefer a round to an oval ball…

All lovers of Association football in America would be overwhelmed with joy if as much interest and painstaking were exhibited in America as in England, but slowly and surely the game is making headway. The devotees of the game in America now are largely made up of the working classes, who have great difficulty in participating in a Saturday match. Another drawback is the difficulty in securing opponents, but it is hoped that in time such difficulties will be overcome, as there may be different classes of men taking interest in the games. It would be hard to count the number of clubs sustaining elevens throughout the country, or how many leagues carry out yearly schedules…

There was an American Association [the American Football Association], but its value, if any, was confined to one district. What it needs is a series of intercity games, and an annual international contest for the championship would serve as a drawing card.

Aside from recognizing the importance of games against teams from other cities and a call for international competition, the article underscores the importance at the time of colleges and universities embracing a sport for it to gain popularity. Philadelphia, and the whole of the United States, was by now deeply enthralled with American college football, and sports coverage in local newspapers reflected this. Indeed, the massive popularity of college football helped to squeeze coverage of soccer out of the sports pages.

Still, soccer-style football was gaining ground on college campus. As the passage above describes, some of this was connected to the violence inherent to how American football was played; the number of regular reports at the time of crippling and deadly injuries from playing American football, be it in high school, college, or club games, is truly shocking to the researcher of today.

While there were growing calls to change the rules of American football to better protect players, and even calls to ban the game entirely, there was also something simpler at play, as an Inquirer report from December 10, 1899 makes clear: “There is a suggestion at Yale, yet to be acted upon, to establish Association football for the enjoyment and improvement of men too light to play the American Rugby game.” In other words, there were plenty of athletically minded students whose physical dimensions prohibited them from safely playing American football but who still wanted to participate in physically and mentally demanding team sports. As the Inquirer said in an article published on December 31, 1900 — describing sentiments that will be familiar to readers today:

The exponents of college football generally assume an antagonistic or patronizing air when Association football is mentioned. There should be no opposition to the game from them,as the type of men required for the game is different and there is plenty of room for both kinds of football. The sneers of the college football players, I have always noted, have been founded on his own ignorance of the possibilities and beauties of the game.

As we have seen, in November of 1894, the Philadelphia Association professional team had played Princeton, which reports on the game described as the first college soccer team in the US. Developments continued locally. In the winter of 1897, the freshman and sophomore classes at the University of Pennsylvania organized teams for a interclass game. At the time of the passage quoted above, the birth of intercollegiate soccer was five years away. When it did arrive — and Haverford College would be the leading exponent — it would always be in the shadow of collegiate American football.

But what explains the slow headway of the soccer? As was described earlier, the Panic of 1893 was certainly a factor. As the passage above makes clear, soccer’s “devotees” came from the working classes. The economic crisis that followed the Panic of 1893 had its deepest effects on those neighborhoods in Philadelphia that were home to the city’s soccer fans, clubs, and players. That the American Football Association (AFA) is referred to in the past tense in the passage above is because the association had ceased operations beginning in 1899, being revived, along with the American Cup tournament, in 1906. One of the reasons for the association’s dissolution was ongoing labor strife in the textile mills of the Fall River district of Massachusetts, a region that was key to the AFA’s roster of participating teams. This, along with creeping professionalism in the New York and Northern New Jersey districts meant, as C.K. Murray writes in Spalding’s Official Soccer Foot Ball Guide of 1910, that the AFA was “unable to cope with the predatory efforts of the prominent clubs to secure crack players” and so “threw up the sponge.”

Writing in the Spalding’s Association Foot Ball Guide of 1905, C.W. Hurditch also points to the introduction of professionalism into the sport through the short-lived American League of Professional Foot Ball (ALPF) in 1894 as another economic factor that disrupted the growth of the game. After describing the gains made locally by the PAFU, Hurditch continues,

Unfortunately about then the base ball leagues thought the time was ripe to exploit the game, and selecting the best players from from various clubs, placed four professional teams in the field, and thus weakened and disorganized the amateurs. In spite of this, the public did not sufficiently appreciate the fine points of the game, attendances and gate receipts were not such as would warrant the keeping up of the high-salaried players that had been signed, and the natural consequence followed. Association foot ball received such a shock that it took years to recover, in fact, it looked at one time as if it had died a natural death

There are several problems with Hurditch’s assessment. First, six teams participated in the ALPF. Second, in Philadelphia at least, the “best players” did not sign with the Phillies but signed with Philadelphia’s other professional team, Clement Beecroft’s Philadelphia Association team. Third, the PAFU was struggling to keep enough teams in the league to maintain a regular schedule two seasons before the first baseball-backed ALPF team played its first game. Fourth, those members of the public that did appreciate “the fine points of the game” supported Beecroft’s team rather than the Phillies. Fifth, the poorly organized, and poorly publicized, schedule of ALPF games was also a significant factor in poor attendance. Sixth, Beecroft’s team, which became the Manz team in 1895, remained a professional team until the AFA reinstated the amateur status of players who had played on ALPF teams such as the Phillies, as well as teams that had been a part of the other professional league, the American Association of Professional Football Clubs (AAPF), which included the Philadelphia Association team and had Beecroft as league president. The “keeping up” of professional salaries was thus attainable. In the end, it is simply too much to accept that the ALPF, a league that collapsed two weeks after its first game, could have the negative impact that Hurditch attributes to it. Additionally, one could make a strong case that it was precisely the success of the professional Philadelphia Association/Manz team that helped keep interest in soccer alive in Philadelphia during the troubled middle years of the 1890s. It certainly kept reports of soccer in area newspapers.

Pennsylvania’s Blue Laws, which prohibited the playing of games on Sundays and remained in effect until the 1930s, were another inhibitor locally to the game’s growth. The difficulties for a soccer player, working long hours six days a week (if one were fortunate enough to have employment during these times of economic upheaval), in meeting with his team and then traveling across the city for a Saturday afternoon game in an era before the widespread ownership of automobiles are obvious and just as applicable to the soccer fan of the day. And make no mistake, the Blue Laws were no joke. A Philadelphia Times report from October 29, 1894 details the arrests of seven young men for practicing on a Sunday “in their foot-ball clothing” for a rugby game the next week. The report notes, “as many more as were arrested made their escape across the fields when the police arrived.” The arrested players — who weren’t playing an actual game but were simply practicing — were released on bail pending a hearing “on the charge of violating the Sunday laws.” On May 13, 1897, the Times reported that a bill had been introduced in the Pennsylvania legislature to make the penalty for playing “base ball and foot-ball” on a Sunday punishable by a $25 fine or ten days’ imprisonment. In today’s dollars, that’s a nearly $700 fine.

The scheduling challenges of not being able to play games on the only day most everyone had off are obvious, particularly in terms of intercity matches. Only being able to schedule games on Saturday afternoons during the shortening days of fall and winter before the widespread use of electric lights for illuminating playing fields also restricted the ability of Philadelphia teams to host visiting teams from other states, whose players might also have to miss work on a Saturday in order to travel by train from New York, Northern New Jersey, or as near as Trenton, for a game in Philadelphia.

Winter conditions were also a factor. The climate of the British Isles is such that play is only occasionally disrupted by winter conditions. Along the North Atlantic coast of the US, such conditions can be a concern from November through April and presented continual obstacles to the completion of league schedules. And when winter games were played as scheduled, conditions were terrible for fans and players alike. Given the choice between standing outside for two hours in frigid temperatures, cold winds, freezing rain, sleet, and/or snow to watch soccer, and sitting inside a gymnasium to watch the recently invented game of basketball, the casual Philadelphia sports fans might understandably choose the latter, whatever their appreciation of “the fine points of the game.”

That soccer was a “foreign” game was also a factor in inhibiting its growth. Setting aside the impulse to celebrate “American” sports like baseball (derived from the British game of rounders), American football (derived from the English game of rugby), and basketball (originally played with a soccer ball), numerous newspaper accounts refer to soccer as “the English game” and emphasize that its most fervent supporters typically resided in the largely English, Irish, and Scottish industrial neighborhoods of the city. In a nation of immigrants, soccer would always have, and indeed benefit from, immigrant players. But it was, and remains essential that native-born players begin to participate and excel in the game in numbers that equal and then surpass immigrant players that soccer would begin to claim its place in the wider sport culture. Locally, the founding of the Lighthouse Boys Club in 1897 would prove to be instrumental in the development of some of Philadelphia’s best youth players, who would go on to play on some of the most important Philadelphia teams, and indeed, most important teams in the US, at the amateur and professional levels, as well as on US national teams for much of the 20th century.

Despite all of these factors, the prospects for soccer in Philadelphia were about to change for the better, with interest from elite sections of Philadelphia society in the working class game being the important catalyst.

Philadelphia cricket clubs embrace the game

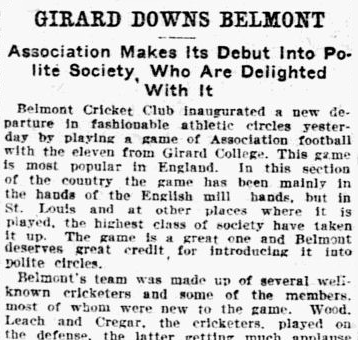

On December 9, 1900, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported on a game between members of the Belmont Cricket Club and students at Girard College. Under the headline, “Girard Downs Belmont: Association Makes its Debut Into Polite Society, Who are Delighted with It,” the Inquirer reported,

Belmont Cricket Club inaugurated a new departure in fashionable athletic circles yesterday by playing a game of Association football with the eleven from Girard College. This game is most popular in England. In this section of the country the game has been mainly in the hands of English mill hands, but in St. Lois and other places where it is played, the highest circles of society have taken it up. The game is a great one and Belmont deserves great credit for introducing it into polite circles.

Whereas the Belmont team was largely made up of inexperienced players, because playing American football was banned on campus Girard College had been playing the game for some time and had already played Frankford, so it comes as no surprise that the high school players of Girard College defeated the adult players of Belmont, 4-1 (an Inquirer article on January 3, 1901 puts the result at 4-0). The Inquirer noted in its match report that, despite the defeat, “A large crowd of club members watched the game with the keenest interest and they were delighted with it.”

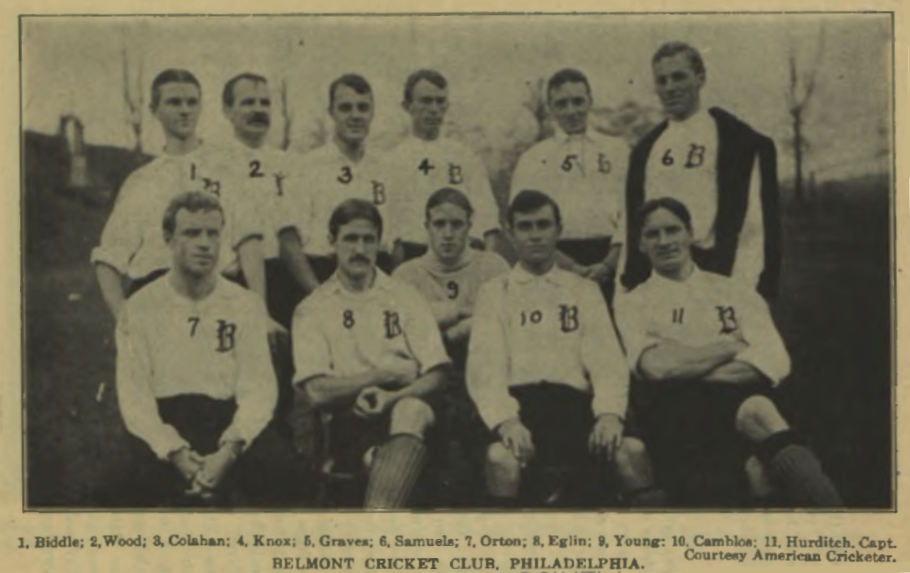

Hurditch agrees on the importance of the Belmont-Girard match, writing it “was just what was wanted to boom the game, for those who had come to sneer left the ground convinced that ‘there was something to it,’ and that science would triumph over brute strength.” (Hurditch identifies himself as responsible for Belmont adopting the game and also suggests, against all evidence, that the Girard “youngsters” actually lost.)

On December 20, a headline at the Inquirer read, “Association Football Being Given A Boost: Best Class of People Now Taking Up the British Game.” The report described,

Much to the delight of many who know the game, association football is at last in a fair way to become popular in and around Philadelphia among the highest class of her sportsmen. Two weeks ago, the Belmont Cricket Club played their first match, but already the Linden Cricket Club, of Camden, and the Philadelphia Cricket Club, of Wissahickon, have followed their lead. Merion and Germantown, it is said, will also take up the game. This would make an excellent league and the quality of the contestants should at once insure the game a certain degree of popularity.

That league, the Associated Cricket Clubs League of Philadelphia, would be formed in 1902 and is the oldest continuously operated league in the US.

By now, Germantown Academy and the Delancey School (which merged with Episcopal Academy in 1915) had also joined Girard College in taking up the game. Belmont continued play with a series of games against Brill and Eddystone at the club’s Elmwood grounds in West Philadelphia at 48th Street and Chester Avenue. It won its first game on December 29, 1900, defeating Brill, 1-0. On New Year’s Day 1901, Belmont played Girard College again, this time finishing as the 1-0 winners.

Meanwhile, existing Philadelphia soccer teams had formed a new Philadelphia Amateur Association Football League involving six teams: North End (home field being the North Philadelphia Base Ball Park), Albion (Broad and Jackson Streets), Blackburn Rovers (same grounds) Nicetown (Pulaski Avenue and Bristol Street), Frankford, and Brill. Also organized was the Philadelphia Suburban League, which would see the Wayne team as its first champion. At the same time, independent clubs such as Norristown, Wissahickon, Excelsior, Manton, and Fairhill Thistle were arranging games. The Inquirer reported on January 11, 1901, “The Thistle team is made up chiefly of the old Manz team, former champions.”

Many of these teams organized games against the Belmont side, the new darlings of the press. Hurditch makes the point that the effect of the new interest in soccer from “polite circles” was felt across Philadelphia’s sports landscape: “I have no hesitation in stating this proved the required stability to Association foot ball, for the following year saw the interest redoubled, and it assumed the proportions which now characterize it.”

Match reports and other local soccer news at the Inquirer, now once again a regular feature of its sports coverage, make repeated references to large crowds attending games. Attendance for a game between Nicetown and Blackburn on January 12, 1901 was put at “1000 people.”

Philadelphia’s first international game

Philadelphia’s first international game

Belmont Cricket Club’s embrace of soccer had drawn the attention of Philadelphia’s upper class, and along with it, increasing coverage of the game in local newspapers, principally the Philadelphia Inquirer. On October 8, 1901, Belmont would again further the sport’s place in the city’s sports landscape when it played the English cricket team led by B. J. T. Bosanquet in the city’s first international game at its home grounds in West Philadelphia, a game that would prove to be a turning point for soccer in Philadelphia.

That “the Gentlemen of England” defeated “the Gentlemen of Philadelphia,” 6-0, came as no surprise; the Inquirer reported “quite a few” of the players on “Bosanquet’s XI” had “represented the picked team of England in international matches.” (For more on the game, see Philly’s first international.) More important than the result was the interest aroused by the game. The Inquirer reported on October 20,

The recent international association football match between B. J. T. Bosanquet’s team of amateur English cricketers and the Belmont Club was the means of arousing a pronounced public interest in a game that was previously comparatively unknown to the sports loving residents of this city, and a number of local clubs have been organized as a consequence, while the ranks of the older organizations have been so strengthened that several of them intend putting two teams on the field.

Among those whose interest was aroused was Connie Mack, manager and part-owner of the Philadelphia Athletics team of baseball’s new American League. By Thanksgiving, Mack was fielding a soccer team, playing two shortened games that day against Belmont and West Philadelphia, winning both. While Mack’s team would play no more than one season, that a non-soccer sports figure saw potential in the game was yet another signal that soccer in Philadelphia had turned a corner and was here to stay. (For more, see Connie Mack’s soccer team.)

The Philadelphia Association Football League, now operating under the name of the Allied Association Football Clubs of Philadelphia and with a growing roster of clubs, began to concern itself with improving the quality of games. The Inquirer reported that among the topics for a league meeting in December, 1901 was “the advisability of having neutral referees for all the large games.”

Despite all of the positive developments, college football was still the center of attention. On Saturday, November 30, 40,000 spectators filled Penn’s Franklin Field for the Army-Navy game. The Inquirer’s roundup of soccer results on December 1 began, “Association football yielded the palm to the college game yesterday afternoon, and as a result of the attraction at Franklin Field two or three of the association matches on the card were cancelled owing to the difficulty the managers experienced in getting together a team.”

Here to stay

Recounting the history of soccer in the US in the Association Foot Ball Guide of 1905, C.P. Hurditch aptly describes the early history of soccer in the US as “spasmodic.” He continues,

But, of course, this state of things could not last—sooner or later the boom was bound to come and the merits of the game recognized by the sport-loving American public. And to a very large extent the palm for the recent spurt of the game in the East must be awarded to Philadelphia, for it is undeniable that through the efforts, individual and collective, of the Quaker City enthusiasts, various large cities of the United States have taken up “Socker,” and leading colleges and schools have and are recognizing the healthful benefits to be derived therefrom.

Spalding’s Official Association “Soccer” Foot Ball Guide of 1907 declares, “The development of the game in the big cities during the past decade, New York and Philadelphia are yet far in the lead, both in the number of clubs and the general interest in the sport”.

In the 30 years between 1871, when the Philadelphia Inquirer reported on what may have been the first soccer game played in Philadelphia, and the city’s first international friendly in 1901, soccer in Philadelphia had weathered its abandonment by area colleges in favor of what would become American football; had seen teams formed in the city’s English, Irish, and Scottish immigrant communities for one-off games, teams that in turn were part of the formation of the city’s first organized league; seen the start of intercity play against teams from as close as Chester, Wilmington, and Trenton, and as far away as Northern New Jersey, New York, and Pittsburgh; was instrumental in the founding of the first two professional intercity leagues in the United States; had won the city’s first “national” soccer championship; and had survived an economic crisis that may have been worse than the Great Depression.

Philadelphia’s football history stretched back to the Lenape people who settled the area before the arrival of European colonists, colonists who brought their own football traditions with them. These traditions continued within the new emerging culture as America won independence from Great Britain and created its own identity through the first half of the 19th century and the Civil War. And while Philadelphia was behind early centers of soccer in the US such as Northern New Jersey’s West Hudson region and Fall River in Massachusetts after the the development of the Laws of the Game in 1863, by the beginning of the 20th century it had emerged as a leader of the sport in the country.

Philadelphia’s soccer history had only just begun.

Take a bow Mr. Farnsworth, that series was phenomenal. Thank you for writing it. I hope you had as much fun researching and writing it, as much as I did reading it.

Thank you for you kind words (and comments throughout the series) — I had a blast! I’ll soon be continuing with a look at Philly soccer in the 1900s and 1910s.

Hopefully your great series of articles will initiate more interest in the history of the beginnings of the American sport of the Soccer in this country.

You were right to think the 1871 game may have been an Irish Gaelic game. I now have them listed in my Gaelic game files.

Mel Smith

Sir, it is an honor to see a comment from you on my series, much of which could not have been done without the ground-breaking work that you did before me. Your books are essential reading for anyone interested in learning more about the early history of football in all its varieties in the US.

Best,

Ed