Awareness of association football — or soccer — as something distinct from rugby or American football is evident from Philadelphia newspaper accounts by the end of the 1870s. In July, 18778, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported on “healthy outdoor sports in which Englishmen delight, and which they seem fated to remain unrivaled” such as “foot-ball.” An Inquirer article from November, 1878 describes “the application of the electric light to novel uses,” namely a football match played in Sheffield, England attended by some 30,000 people. Attentive readers of the Inquirer could also learn about non-British football: an article reporting from Japan in August, 1879 describes what can only be a game of Kemari.

Readers of Philadelphia newspapers in the 1880s would also have found reports on British soccer. One report from August, 1885 notes that the FA had finally allowed teams fielding professional players to enter the FA Cup tournament. Echoing the centuries old preoccupation with football-related violence, a report from November, 1885 describes, “The football season in England has been in progress long enough to produce two deaths besides a number of broken limbs.”

Such awareness was at times strangely inconsistent on the part of the Philadelphia Inquirer. In November, 1885, the Inquirer observed, “A rule forbidding football players to touch the ball with their hands would make the game literally football and would save many suits of valuable clothing, to say nothing of an occasional more or less precious life,” neglecting to mention that such a rule had been in place in soccer for nearly two decades.

Readers could also find soccer-related advertisements. In June, 1889, James S. Earle & Sons Galleries at 816 Chestnut Street” advertised “‘A Football Match’ between England and Scotland, and many beautiful WATER COLOR DRAWINGS.'” Interestingly, the artwork is among a group described in the ad as “Among the recent arrivals of suitable subjects for BRIDES”.

Information about American soccer developments was also available in Philadelphia newspapers, such as an announcement of “The Newark football team[‘s]” tour of Canada in June, 1885. This “Newark” team was actually the Kearny, New Jersey ONT (“Our New Thread”) team sponsored by the Clark Thread Company, which had just won the first American Football Association’s American Cup final, defeating New York FC, 2-1.

The American Football Association (AFA) had been organized in 1884 in Newark, New Jersey, and the association was the first of its kind in the United States, as well as the first outside of England and Scotland. The AFA’s American Cup tournament was the first mechanism for declaring a national soccer champion in the US, but its participants never came from outside of a foot print that stretched from Boston to southeastern Pennsylvania. Thus, the AFA was never truly a national organization, but, at the time, neither was baseball’s National League.

The history of the AFA would prove to be tumultuous — it would suspend the American Cup Competition from 1899 until 1905 –and through much of its history, the AFA would be viewed in the increasingly nativist cultural climate in the US as being too Anglo-centric. The association would begin to see its influence subside in 1913 with the founding of the United States Football Association, and the American Cup tournament would be supplanted by the National Challenge Cup, which also began in 1913 and is known today as the US Open Cup. Nevertheless, the AFA’s importance in standardizing rules and facilitating the arrangement of matches between clubs from geographically disperse areas would be instrumental in the development of the soccer in the US.

The role of the Clark Thread Company in the founding of both the AFA — the association’s founding meeting took place on company property and the company contributed funding to the association — and the ONT team is indicative of larger trends in the early development of American soccer. As Roger Allaway describes in Rangers, Rovers & Spindles: Soccer, Immigration and Textiles in New England and New Jersey (2005), the Clark Thread Company had been founded in Paisley, Scotland and opened its first mill in Newark in 1866. In 1880 it opened another mill in Kearny, New Jersey. Initially, Clark had been able to hire workers for its New Jersey operations directly from its mills in Scotland. But a change in US labor law in 1885 meant that immigrants from Scotland had to wait until they got to America before they could be hired.

Similar trends occurred in other early hotbeds of soccer in America: cotton workers from Lancashire working in mills in the Fall River, Massachusetts; silk workers from Macclesfield immigrating to the center of American silk manufacturing in Paterson, New Jersey; thread workers from Paisley working in factories in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, as well as Kearny. As Allaway makes clear, that soccer flourished in the West Hudson and southeastern New England areas is directly related to the fact that textile workers who settled there came from areas in Britain in which soccer first spread into the working classes. As we shall see, those areas that were the original centers of soccer in Philadelphia — particularly the North and Northeast Philadelphia neighborhoods of Kensington, Frankford, Port Richmond and Tacony — were the areas in which British immigrant workers were concentrated and the centers of textile production in Philadelphia.

Philadelphia’s first soccer league

We can deduce from reports in Philadelphia newspapers throughout the 1880s of soccer news from Britain and elsewhere in the US that there was local interest in soccer developments. And from such interest, it surely follows that the game was being played in Philadelphia, whether at the annual picnics of ethnic organizations, as had been the case with the Irish Nationalists in the early 1870s, or in one-off contests between ethnic-based or workplace-based sides, or even in impromptu pick-up games. But the fact remains that throughout almost the entirety of the 1880s, there are no newspaper accounts of Philadelphians playing soccer. What Philadelphia lacked was an organized league to sharpen, sustain, and grow such interest. In 1889, that would change.

On July 18, 1889, a notice appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer under the heading “To Football Clubs” which stated that the secretary of the Alma Football club of Newark, New Jersey, George H. Shaw,

would be glad to hear from all secretaries of Pennsylvania clubs playing under Association rules, in regard to arranging individual matches for the coming season, also with object of getting the secretaries of Pennsylvania clubs to combine and select a State team to play an interstate game against the New Jersey State Football League’s team.

Three teams — Kensington Rovers, Philadelphia North End (nicknamed the “the Stentonites” and the soccer team of the North End Cricket Club), and the Chester Volunteer Athletic Association — announced their intention to form “a League for the State of Pennsylvania” on September 16, 1889 and invited “all organized clubs playing under association rules” to a meeting to be held “at the southwest corner at Third and Lehigh Avenue” on September 28 “to elect officers, choose a trophy and rules for its award.” The Times reported on October 7 that, at a meeting including representatives of North End, Eddystone, Kensington Rovers, Chester Volunteers, Philadelphia Athletic, Philadelphia Association, and Philadelphia Shamrock, it was voted “to make the entrance fee $10 and play the cup game on the percentage system.” The $10 league membership fee was not insubstantial; $10 would be about $260 in today. Nevertheless, before the start of league play, Philadelphia’s first soccer league, the Pennsylvania Football Union (PFU), was up to seven teams.

That these clubs were announcing their intention to form a league, rather than announcing their own formation, underscores that organized Philadelphia-area soccer clubs were already in existence by this point. A report on the league’s formation in the Times on September 29 noted, “Much interest is manifested in this organization by the different football clubs in this city.” This is further borne out in an essay by CP Hurditch in the 1904-1905 Association Football Guide, issued as part of the Spalding’s Athletic Library. “Prior to the organization of the Pennsylvania Association Foot Ball Union,” Hurditch writes, “the game had been played fairly steadily each season by the purely British residents.” Melvin I. Smith records in Evolvements of Early American Foot Ball (2008) that Philadelphia North End had played Trenton Rovers on January 19, 1889 in a punishing 9-0 loss at Hetzel’s Grove in Trenton. The Eddystones had played Trenton Association twice in 1889, winning 3-2 at Chester Park on February 23, and playing them away on July 4, but the result is not available for that game. As we shall see, games against Trenton teams would prove to be important in laying the foundation for league soccer in Philadelphia.

The Kensington Rovers and Eddystone had met at Chester Park on August 18, 1889 in what the Philadelphia Inquirer reported “is said to have been the first game of foot ball ever played by electric light,” nearly eleven years after the Inquirer report on the game in Sheffield under electric lights in 1878. While the report says the game “was played after the English Rugby rules,” that may be a reporting error for the Inquirer further describes the game as “entirely different from the American college game” and says the final score was “Kensington one goal, Eddystone nothing.” At this point, American football was more similar to rugby than “entirely different,” and the final scoreline sounds more like a soccer score than a rugby one. Indeed, Smith records the game as having been one of soccer, not rugby.

A meeting held on October 19 in the club rooms of the Philadelphia Association Athletic Club resulted in the election of Clement Beecroft as president pro tem of the PFU and the announcement of “tournaments to be given in different parts of the State during the present season for a handsome gold and silver cup.” Beecroft, who with his brother John owned the Beecroft Bros. sporting goods store at 11th and Chestnut streets, would prove to be “indefatigable,” possessing “unceasing energy,” as the Philadelphia Inquirer described him in January, 1891, and if anyone is worthy of the title of Father of League Soccer in Philadelphia, it is he. Beecroft would later run the North End club and serve as vice president of the Philadelphia Cricket Association.

League play begins

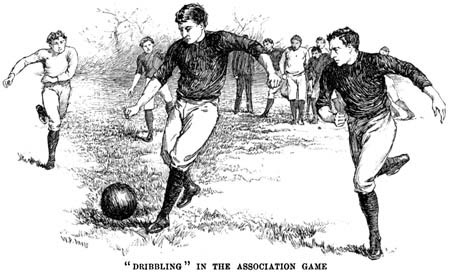

While it is apparent that British immigrant workers were familiar with soccer at this point, two Philadelphia Inquirer reports make clear that the rest of the city’s population was largely unfamiliar with the game. A Philadelphia Inquirer report on October 21, 1889 announcing the inaugural schedule of the PFU explained, “The game as played by these clubs is pure football, no movement being made with the hands or breast, and is far different from the Rugby game.” In a report on November 6 — “An English Game by English Players” — the Philadelphia Inquirer further explained players’ positions, different as they were “from the popular American or Rugby game.”

With the exception of Thanksgiving and Christmas fixtures, the league’s games would be played on Saturdays because Pennsylvania’s Blue Laws forbade Sunday games. Two inaugural PFU matches were scheduled for November 2 at the Chester Base Ball ground, with the Chester Volunteers to play the Shamrocks, followed by the Eddystones against the Kensington Rovers. It appears only the first of the two scheduled games was played, and it was won by the Shamrocks, with the Chester Volunteers dropping out of the league soon after. On November 9, the Philadelphia Association met the North End club at the Athletic Base Ball Grounds. North End won but, again, the score is not recorded.

More games soon followed. On Thanksgiving Day, a new team, Frankford, played North End in the morning at Wayne Junction in a nonleague game (a Tacony team would also begin nonleague play in March, 1890), followed in the afternoon by a match between North End and the Eddystones, who were described as “at present the champions of the State.” By mid December, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported, “The Pennsylvania Football Union, which is composed of a number of sport loving English residents of this city, is meeting with great success in its encouragement of the exciting game as played in Great Britain.”

That report also noted the PFU was using two of the finest grounds in the city, the already mentioned Athletic Base Ball Grounds, and the Young America Cricket Club grounds at Stenton. Located at the corner of North 25th Street and West Jefferson Avenue (presently the location of the Daniel Boone School), the Athletic Base Ball Grounds were the home of the American Association Philadelphia Athletics and had been the site of the inaugural National League game between the Philadelphia Athletics and the Boston Red Stockings on April 22, 1876. The Young America Cricket Club had been formed in 1854 after the predominantly English-expatriate Philadelphia Cricket Club refused to allow young American cricket players to participate in matches and would go on to be a leader in American cricket before it merged with the Germantown Cricket Club in 1890.

Respectful press coverage continued in the Philadelphia Inquirer throughout the the PFU’s first season, one highlight of which was what may have been the first soccer riot at an organized game in Philadelphia. On March 2, 1890, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported on “the roughest and most exciting game of football (under English Association rules) that has ever been played in this city,” a 1-1 draw between Philadelphia South End (who appear to have replaced the Chester Volunteer team in the league) and Kensington Rovers at the Athletic Base Ball Grounds:

At the commencement of the second half the anxiety of the players to secure the sphere on its return was a signal for the rough play that characterized the latter part of the game…After passing the posts, the ball was picked up by one of the spectators, whose object was to place it in the hands of the goal-keeper, but ere he could accomplish this, the centre half back of the South End, made a terrific rush at the unfortunate man, and before he realized his position, he received a stunning blow in the face from the fist of the player. A regular set-to then followed, players and spectators alike joining in the melee. After considerable haranguing the game was continued, but from this out there was little else done but fighting and quarreling…The fight which had interrupted during the game was continued after the match, both player and onlooker being badly used up, and vowing vengeance the next time they meet.

Less than a month later on March 29, 1890, Eddystone won the inaugural PFU championship at their home ground, defeating Philadelphia North End, 1-0.

As had been the case in the West Hudson and southeastern New England regions, the home areas of the founding clubs of the PFU were connected to textile production. Nathaniel Burt and Wallace E. Davies describe in Philadelphia: A 300-Year History (1982), “Philadelphia produced more textiles than any other American city, and was also the world’s largest most diversified textile center.” There were “mills all over the city” and Kensington was “a sort of textile enclave, inhabited by English emigrant weavers.”

Chester and Eddystone, just south of Philadelphia in Delaware County, were also areas of textile production. The textile firms Aberfoyle Manufacturing Company and Irving & Leiper Company were both important employers in Chester. William Simpson had a long and successful career as a textile printer in Philadelphia when he began to purchase tracts of land in Eddystone for the new Eddystone Print Works, and by 1885 he owned virtually all of the land in the town. The 1880 census showed over half the population of the town was foreign born, with the majority being from England and France. The soccer-textile connection is also apparent further outside of Philadelphia in Scranton and Wilkes-Barre where teams with names such as Scranton Caledonians, Wilkes-Barre Lace Factory Rangers, Wilkes-Barre Albion, and Wilkes-Barre Wantibes were playing by the fall of 1888.

The series continues later this week.

The way that riot was described (toward the end of the article) was just awesome. The writing style back then was so cool.

.

It’s just amazing that our country of immigrants, especially from England, Ireland, etc., did not adopt soccer the way the rest of the world did. Kind of astonishing.

.

This whole series is amazing. Awards must follow.