Photo: Earl Gardner

In MLS, teams are supposed to be on an equal financial playing field. No manager is brought in to avoid relegation or juggle the egos of 18 of the highest salaried athletes on the planet. Instead, every club believes they are one season away from emulating the 2011 Philadelphia Union’s rise from expansion season punching bag to postseason competitor. So a manager in MLS is brought in to engineer these one to two-year turnarounds, and those who succeed are often rewarded with the power to shape a club in their image.

John Hackworth has had just over one-and-a-half years (57 matches) to take a Philadelphia Union team that was in danger of earning a recurring role on a midday soap opera and turn it into a contender. Hackworth has had a hand in trades, a college draft, and key acquisitions like Conor Casey, but a manager earns his paycheck by putting a team onto the field that is better prepared than the opposition.

Viewed through this lens, how should John Hackworth be evaluated after the 2013 season?

Lineups: Back five

Before a match, a coach’s job boils down to two decisions:

- Who starts on the field

- How do I tell them to play.

In 2013, Hackworth used a very consistent lineup, with the regular back five and Brian Carroll starting over 30 times. The only other player to start more than 30 times this season was winger Danny Cruz, who was deployed as a hybrid winger/wide striker.

Consistency can help a team, and putting the same back line out match after match is particularly important for a young team without an identity.

As with all things, however, there are tradeoffs.

Though he has proved a solid defender and one that any coach would call an exemplar of hard work, character, and attitude, Ray Gaddis has not developed into a modern left fullback. The modern fullback gets forward, carries the ball, takes on defenders deep in the attacking third, and generally acts as an outlet for what has become a frustratingly crowded midfield. Strikers drop deep, teams deploy double pivots, and in response managers push their fullbacks up the pitch to give width. Gaddis was uncomfortable on his left all season, and WhoScored.com credits him with only 4 key passes and no completed crosses (of 23 attempted).

More damning is that Montreal, a team that treated the playoffs like a dentist’s visit for the latter third of the season, was the only playoff team to allow more goals at home than the Union.

Hackworth gave Fabinho a tryout at left back, but the Brazilian’s all-too-apparent disinterest in defending other soccer players proved Gaddis was the only acceptable option. Gaddis’ lack of development on the left, and the Union braintrust’s inability to bring in cover that, at minimum, could push the young fullback, was troubling from March through October.

The left back situation was emblematic of Hackworth’s approach to the entire back line. The whole season seemed to be an extended pilot test for a group of players that were as talented as any in the league but fell in and out of a groove too often. When they were out of a groove, the Union simply had nobody waiting a turn in the first 11. The backup right back was Michael Lahoud (or Ray Gaddis), and the backup central defenders were Sheanon Williams and… well, let’s just hope Jeff Parke takes good care of his body.

In the end, it’s difficult to tell whether Hackworth overly trusted or just had a blind eye for his back line. With Zac MacMath fully entrenched in net, Amobi Okugo undergoing the midfield-to-defense transition usually reserved for those who find they don’t have the pace for the pro game, and Jeff Parke dropping a veteran anchor into central defense, one would have expected more than a two-goal improvement in goals allowed. Certainly this is an unfair measuring stick, but more damning is that Montreal, a team that treated the playoffs like a dentist’s visit for the latter third of the season, was the only playoff team to allow more goals at home than the Union (MTL: 19, PHI: 18).

The Union defense was far from awful, and it will get better. But problems that should have been addressed early on festered throughout the season.

Lineups: Midfield

Regardless of how it happened, a thin bench definitely contributed to the constant setup in the back.

The midfield, however, was quite a different story. Brian Carroll was anchored in the defensive midfield position, but options were abundant for the other spots. Those options only increased once Conor Casey and Jack McInerney forced Sebastien Le Toux into a wide role.

From day one, Hackworth put out a team that seemed built to counterattack. As the season evolved, the lineup became a dead giveaway that the Union would be attacking fast up the wings, and, more worryingly, that there was no backup plan. In Sebastien Le Toux, Fabinho, and Danny Cruz, Philadelphia were using wingers with speed and stamina but no real ball retention skills. More on that below.

As the wings became one-dimensional, Hackworth seemed without a plan for his central midfielders. Brian Carroll was usually paired with Michael Farfan or Keon Daniel, but neither partner provided a consistent foil to the captain’s preferred deep-lying role. An experiment with Kleberson in a traditional No. 10 role was so short-lived that it did little more than raise question marks over the Brazilian’s injury status for the remainder of the campaign.

Lineups: Strikers

While there were few options in the back and midfield choices seemed to fit the coach’s strategy (even if they limited his ability to make in-game adjustments), justifying the evolution of Hackworth’s striker decisions is a much harder sell.

Early in the season, Conor Casey’s fitness and Jack McInerney’s form made decisions easy. After starting the year with Le Toux alone up top, Hackworth deployed Mac and the Frenchman in the next three games. When Casey was healthy, he and McInerney led a line that was held scoreless only once from April 6 through the end of June. This culminated in a run of 10 goals in 4 games as the Union thrashed Columbus and New York and should have done better in draws with Dallas and Real Salt Lake.

Over the last ten games of the season, only Chivas (8 pts), DC (3 pts), Montreal (8 pts), and Toronto (8 pts) accumulated fewer points than the Philadelphia Union’s nine.

But when McInerney left his confidence on the plane back from the Gold Cup, Hackworth responded by increasing the pressure on the young striker to play mistake-free soccer. Though the Union went 2-1-1 directly after McInerney’s return, the striker’s minutes began to dry up.

In those first four games, McInerney played at least 80 minutes every match, and Mac and Casey were partnered for at least 80 minutes in three of four matches. Over the final 10 matches of the season, McInerney saw 80 minutes just once, when he was subbed off in the 80th against Montreal on the last day of August.

Few would argue that the young striker was low on confidence, but nobody can argue with the results that coincided with McInerney’s reduced minutes: Over the last ten games of the season, only Chivas (8 pts), DC (3 pts), Montreal (8 pts), and Toronto (8 pts) accumulated fewer points than the Philadelphia Union’s nine.

Lineups: Substitutions

It is difficult to judge Hackworth as a coach based on his substitutions. One can argue that Hackworth should have pushed for more defensive options to use late in games, but he actually didn’t have any. Assigning blame for that goes too far up the ladder for this discussion.

Instead, we can focus on the options Hackworth did have and how he used them. Antoine Hoppenot and Aaron Wheeler were the most frequent lineup additions, while Michael Farfan and Sebastien Le Toux were in the next tier with seven bench appearances each. Hackworth made a sub before the 70th minute in all but four league games in 2013, indicating that he was making adjustments fairly consistently whether the Union were ahead, tied, or trailing.

While the Union were actually the 4th best in MLS in points/game earned when trailing at halftime (0.71), only the inimitable Toronto (0.73) and DC United (0.62) earned fewer points per game when tied at halftime than the Philadelphia Union’s 1.06.

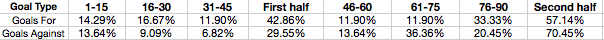

This is where it gets interesting. It should be no surprise to regular viewers that the Union scored more goals in the second half than the first (approximately 57 percent in the second). But opposing teams scored 70 percent of their goals in the second half, with over 56 percent of those coming in the final 30 minutes.

A detailed breakdown shows an even more curious pattern. The Union gave up 16 goals between the 60th and 75th minutes of games, a full 36 percent of the goals they allowed. During that same period, Philly only scored 5 goals, or about 12 percent of the goals they tallied on the year. That disparity is enormous.

Luckily, the Union outscored their opponents 14 to 9 in the final fifteen minutes of matches, alleviating some of the damage done in the previous frame. But that should be small consolation. These numbers indicate that the Union were hitting a wall, and that John Hackworth was either making ineffectual (or damaging) substitutions, or his hand was being forced as the team suddenly had to chase a result late in the match.

There is more data suggesting that Hackworth was unable (for personnel reasons) or did not recognize what changes needed to be made as games wore on. While the Union were actually the 4th best in MLS in points/game earned when trailing at halftime (0.71), only the inimitable Toronto (0.73) and DC United (0.62) earned fewer points per game when tied at halftime than the Philadelphia Union’s 1.06. This is particularly disturbing when you consider that only Los Angeles (22), Chicago (18), and Dallas (18) entered the break tied more often than the Union (17).

While the Union outperformed playoff teams in points per game earned when trailing at the half and had only a minimal difference from playoff teams in points per game earned when leading at the half, they earned 0.46 fewer points per game than playoff teams when tied at halftime.

If you want to know where that playoff spot went, look no further than the second half, particularly the 60th through 75th minutes, which is the period when a manager normally assesses the team’s fitness and position in the game and makes his biggest in-game moves. These 15 minutes of hell were the difference between the Union having a playoff season and going home early.

Unfortunately, this is not just a 2013 problem.

In the 23 matches with Hackworth at helm in 2012, the Union gave up 10 goals between the 60th and 75th minutes. That is nearly a third (32.36 percent) of the goals they gave up under the first time MLS head coach. This is clearly an issue that Hackworth needs to address. Is he waiting too long to make substitutions? Making the wrong moves? Or does his team simply not have the fitness to last through the 75th minute? Philly’s fightback instinct (14 goals in the final 15 minutes in 2013, 9 under Hack in 2012) suggest the fitness is there. So something else must be at issue.

On-field tactics

An observer seeking to determine whether John Hackworth is stubborn or pragmatic would have a difficult job. The Union manager has moved some distance from his original tactical proclamations of possession and width. On the other hand, once he discovered a counterattacking philosophy that, behind Jack McInerney, bore seemingly endless fruit, Hackworth appeared to lay his cards on the table and put forth inflexible teams that were capable of but one system.

Over the first four months of the season, the Union spread the offense around. The midfield offered up five non-cross assists, with Michael Farfan, Keon Daniel, Danny Cruz, and even Brian Carroll contributing. During the second half of the season, Kleberson and Fabinho tallied the only assists from midfield, and one of Fabinho’s came through the air.

So what changed?

Well if you watched the Union play this season, you are probably aware of video recording. Other MLS teams watched Union games, saw that they had trouble entering the final third if the vertically inclined wingers could not get behind a defense, and adjusted accordingly. Meanwhile, Philly’s central midfield continued to drop deeper as counterattacking opportunities became less frequent. A hole developed in the middle of the pitch, and if a striker did not fill the space, the Union essentially had no path out of the back.

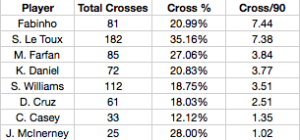

Fabinho, a player that did not take corners or free kicks, averaged 7.44 crosses per game.

Danny Cruz became increasingly marginalized, rarely attempting more than 20 passes per game. On the other wing, Sebastien Le Toux pushed higher to compete for the long balls that became the team’s stock and trade. Conor Casey’s size became a crutch rather than a secondary route to goal.

Doubling down on direct

Modern soccer is pushing the playmaker wide. Javier Morales and Diego Valeri led their teams to the top of the West by escaping the cramped middle of the pitch and acting as creators from wide positions. The Union actually saw this creative shift play out in their first match of the season, when Keon Daniel earned his only assist of the year playing on the wing.

But when faced with the decision to either move his creative players wide or double down on a more direct approach, there can be little doubt that John Hackworth put his chips on direct. Danny Cruz stayed on the right, while Sebastien Le Toux and Fabinho brought an early crossing game to the left.

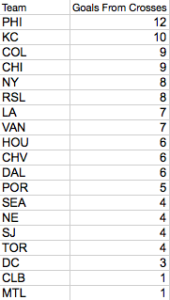

From July through October, Philly scored 7 goals off crosses and 4 from open play without a cross.

So direct, but with a twist. Since Le Toux and Fabinho could not get behind the defense, they settled for early crosses. Fabinho, a player that did not take corners or free kicks, averaged 7.44 crosses per game. Only 21 percent of those crosses found a Union player, meaning that possession was given away approximately 80 percent of the time.

A 21 percent cross completion rate is no outlier. Keon Daniel completed the same percentage of crosses and Sheanon Williams completed about 19 percent. It is the volume of crosses from Fabinho that truly speaks to the change he cemented in the Union strategy. Daniel, Farfan, and Williams all averaged between three and four crosses per game in 2013. Le Toux, with dead balls included, is the only non-Fabinho player to average more than four crosses per game. Crosses are not ineffective. But for a team that struggles to get midfielders into the box, they are hardly ideal.

The change in Hackworth’s tactics is illustrated even better by looking at where the goals came from in the second half of the season. Through the end of June, Philadelphia scored 14 goals from open play that did not come from a cross and 5 goals from crosses. By the end of the season, the Union had scored 18 goals from open play that did not come from a cross and 12 goals from crosses. So from July through October, Philly scored 7 goals off crosses and 4 from open play without a cross. Kansas City was the only other team to hit double digits in goals from crosses in 2013.

So while other MLS teams were looking for ways to free up a playmaker, the Union dismissed the idea of playmaking altogether. Instead, they pumped balls into the box and let Conor Casey do his thing. While the goal return doesn’t look too shabby, the Union gave away possession so often that the bend-but-don’t-break defense in the back was put under intense pressure as the opposition poured forward again and again.

Outlook

Sometimes coaches sacrifice their preferred strategy for one that fits the team. Looking at how the Union changed over the course of 2013, that is what one might assume John Hackworth did in his first full year in charge.

But a closer look at Hackworth’s lineups and tactical adjustments lead one to question whether the coach picked a strategy that fit his team, or whether there was something of a self-fulfilling prophecy involved. The Union’s lineups dictated a certain style of play, but what dictated the lineups?

Hackworth said after the 2013 season that he envisions Amobi Okugo as a long-term central defender, closing the door on what many assumed would be Okugo’s eventual progression to the midfield. After a season in which the Union could not pass their way out of a room with no walls, keeping a player with Okugo’s passing range out of the midfield is a decision that could end up defining Hackworth’s tenure.

Keeping Okugo’s skill set in the back speaks to a larger issue for Hackworth: How will the Union fix their supply lines to the strikers going forward? In 2013, the regular starting midfield (Fabinho and Le Toux both included) combined attempted an average of one through ball per game. With McInerney’s movement, that simply is not good enough.

Hackworth has two clear options: He can bring in an attacking midfielder to sit in the hole and be a central offensive hub, or he can catch the current wave and try to make his wide midfielders more dynamic. Keon Daniel and Michael Farfan should both get a shot on the wings, but if the Union decide that playing through Conor Casey is the preferred route in 2014, possession players on the flanks may not fit that strategy.

It was clear from the opening game of 2013, which found Jack McInerney on the bench and Michael Lahoud alongside Brian Carroll, that John Hackworth either did not have a strategy to implement or was not sure he had the right personnel to play his game. Either way, it led to a evolving system that bore fruit in its early, dynamic phase but turned into a static, Route 1 nightmare as the Union collapsed over the final 10 games of the season. This cannot happen again. Jack McInerney cannot take the blame again when the midfield ceases to be effective.

At this point in his career as a head coach, John Hackworth may be neither stubborn or pragmatic. Instead, he may just be reactive. When his team wins, he keeps putting the same guys out there. When they struggle, he doesn’t look for systemic flaws but instead rotates the players who seem to be taking the struggles the hardest.

To succeed with the type of bare bones rosters he has had in Philadelphia over the past one-and-a-half seasons, John Hackworth needs to be proactive. He needs to sort out the root causes of his team’s struggles and not let the appearance of success or failure blind him to the deeper flaws or growth of his team.

After 57 games in charge, John Hackworth and his team remain very much a work in progress.

Great post, Adam.

About half way through reading this, I began questioning why I had renewed my season tickets for ’14.

I think the defining moment for me of Hackworths tenure so far is his Starting of Antoine Hoppenot in the last game of the season. For me that was Hack’s equivalent to starting Stefani Miglioranzi in the Unions playoff game, a baffling maneuver that showed the coach had little confidence in the players who count. It was overlooked by starting Okugo and Kleberson but those were done mostly out of necessity.

My other problems is Hackworths subs come in one of two flavors. Route predictabilty (Hoppenot at 60′) or Throw everything at the wall (8 strikers on the pitch!!!!).

I don’t know what to make of the guy but I am resigned to having him for at least another year.

“The only other player to start more than 30 times this season was winger Danny Cruz, who was deployed as a hybrid winger/wide striker.” … AND I think I just threw up in my mouth a little.

.

Overall I give Hack a C+. I can’t give a coach a B who can’t make the playoffs and starts Danny Cruz ALL THE TIME. He succeeded in bringing stability to the team which was sorely needed. Personally I think Hack is a more of a Player Development guy than a game-day Manager.

.

If the Union don’t impress me this offseason and make the playoffs next year, I will become a loyal television viewer instead of a loyal season ticket holder.

“I think Hack is a more of a Player Development guy than a game-day Manager.”

Bingo! That is Hack’s upbringing. He was worked with youth most of his career. And it’s not such a bad fit with the young age of this squad.

Hopefully Hack grows along with the players he is developing, but I am afraid that it will take a change in management to get the squad over the hump. But that won’t happen for at least one more season. Remember, good Managers aren’t cheap either.

But also keep in mind Hack is doing exactly what he was told to do – stick with the plan. Build young and from within; exercise patience with the squad and eventually it will bear fruit (at least that is the plan).

Good “Player Devlopment Guys” don’t sit good, motivated young strikers in a slump.

“After fifty-seven games in charge, John Hackworth and his team remain very much a work in progress” R U kidding me?!

Wish we had a coach like Caleb who righted the ship in just 1 season with a budget that is unlikely to be much more than what we have here.

See:

http://sports.yahoo.com/news/portland-timbers-caleb-porter-wins-111009682–mls.html

Very frustrating what is going on here in Philly.

Porter’s budget actually was much more than what Hackworth had this season. Porter had 2 DPs and a full salary budget.

There is nothing that Hackworth has said or done that warrants his being retained as manager of the Union. I have said this often enough. Hackworth is not a pro manager and should not be in charge of this team. Nothing personal, he just is not going to move this team in the direction it needs to go.

Sadly, +1.