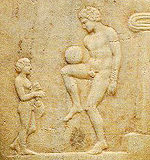

Before soccer there was football. Lots of different kinds of football, many of which also involved handling the ball: Episkyros in ancient Greece; Harpastum in Rome; Zhu Qiu in China; Sepak Raga on the Malay Peninsula, Kemari in Japan, Calcio in Italy (which was revived by Mussolini), not too mention the various kinds of folk football that could be found throughout the Celtic world, some of which survive as the Shrovetide games of Britain. Combine the fact that humans have always liked to kick things with that yin and yang of humanity—competition and cooperation—and the result is that pretty much anywhere you look in the history of the world you will find some form of football. When English explorers began to search for a passage to Asia in the far north coast of North America and, later, they and other colonists began to settle in areas that would become known as Virginia, Massachusetts and the Delaware Valley, it was no different.

The football encountered by Jamestown and Massachusetts Bay colonists

Before there was American soccer there was Native American football. An account of a voyage from England in 1586 in search of the Northwest Passage contains a sidebar entitled “Our men play at football with the Savages” that may be the first recorded “international friendly.”

Diverse times they did wave us on shore to play with them at the football, and some of our company went on shore to play with them, and our men did cast them down as soon as they did come to strike the ball. And thus much of that which we did see and do in that harbor where we arrived first.

Maybe “friendly” isn’t the right word.

William Strachey observed around Jamestown, founded in 1607, “a kind of exercise” among the Native Americans:

They have the exercise of Football, in which yet they only forcibly encounter with the foot to carry the Ball the one from the other, and spurn it to the goal with a kind of dexterity and swift footmanship, which is the honor of it.

Henry Spelman, a member of the Jamestown settlement, was captured and raised for two years by the Powhatan tribe (1609-1610). Of the football played by his captors he says, “They use beside football play, which women and young boys do much play at. The men never. They make their goals as ours only they never fight nor pull one another down.”

When the Pilgrims arrived in 1620, the Native Americans they encountered were playing a game called Pasuckquakkohowog or “they gather to play football.” The account of Roger Williams from 1643 says, “They have great meetings of football playing, only in summer, town against town, upon some broad sandy shore, free from stone, or upon some soft heathy plot, because of their naked feet, at which they have great stakings, but seldom quarrel.”

Thomas Hutchinson’s The History of the Colony of Massachusetts-Bay (1764) says of these Native American sports and games:

Football was the chief, and whole cantons would engage one against another. Their goals were upon the hard sands, as even and firm as a board, and a mile or more in length, their ball not much larger than a hand ball, which they would mount in the air with their naked feet, and sometimes would be two days together before either side got a goal.

In New England Prospect (1634), William Wood also noted “the swift footmanship, their strange manipulation of the ball.” Yet, echoing the kind of cultural disdain for other people’s footballing efforts that is all-too-familiar in English football history, he didn’t think much of the Native Americans technique and tactics: “One Englishman could beat ten Indians at football.”

The football of the Lenape people of the Delaware Valley

The original inhabitants of the Philadelphia region were members of the Delaware tribes of the of the Lenni Lenape Nation. Daniel Denton’s account from 1656 says, “Their Recreations are chiefly Foot-ball and Cards.” The Lenape called their game of football Pahsahéman. Details of how the game was played in contemporary accounts are thin. But in 1971, the Lenape Land Association, which was Pennsylvania-based, published a description of the game.

According to that account, Pahsahéman was played with an oblong ball about nine inches in diameter (called Pahsahikén) made of deerskin and stuffed with deer hair. Marking the ends of the field of play, which was of no set size, were goalposts about 15 feet high and 6 feet across, with no cross bar. One team made up of men played another team made up of women. The teams could be of any size.

Men were forbidden from carrying or throwing the ball with their hands and could only move the ball with their feet. If a man caught or intercepted the ball, he had to stand still and then kick the ball towards the goal or to another man. Women could pass or carry the ball, as well as kick the ball if it was on the ground. Men were not allowed to tackle or grab a woman with the ball but could try to prevent her from passing or try to knock the ball from her hands. Women were allowed to grab or tackle men.

While men could only score points by kicking the ball through the goal posts, women could also throw or carry the ball through. Twelve sticks were used to keep score and whichever team had the most sticks after all twelve were used up was declared the winner. If the score was tied, a play-off would take place until one more goal was made.

The football of the colonists

We know that the early English colonists along America’s Northeast Atlantic coast played football because the laws their leaders wrote tried to ban the game, just as was the case back in England. As early as 1657, Puritan Boston issued an edict banning football from being played on the streets of the town under the pain of a fine of twenty shillings per offender. (In today’s dollars, about $175.) Pennsylvania’s Conductor Generalis, first published in 1711, says that “Bear-baiting, Cock fighting, Football, Bull-baiting, Coits, Nine-Pins, Bowling, Dice, Tennis, Cards, are unlawful games.” Those caught playing them would also face a twenty shilling fine. (Approximately $160 today.)

Why were attempts made to ban football in England and in the colonies? First, the religious philosophies of Puritan New England and Quaker Philadelphia did not look favorably upon “frivolous pursuits.” Second, while there was great diversity in how football may have been played—each town, school, group, possible each occasion, seems to have had its own rules—what appears universal was that the game was violent. And the game was violent not just to people but to property. After reading contemporary accounts of football from Britain, it would be easy to think one was witnessing a riot rather than a sport. Colonists trying to build a new society out of the wilderness need neither injured workers or damaged buildings.

It wouldn’t be until the Nineteenth Century that private colleges in the United States began to play football games with established rules. By 1817, students at the College of New Jersey, as Princeton was then known, were playing ballown. By the 1840s students at Haverford and Girard College were playing huge football games.

Throughout this time, the original inhabitants of the Delaware Valley were being steadily pushed westward. Although some still remain in their original lands—the Museum of Indian Culture in Allentown works to educate the public about Lenape history and culture— most Lenape people now live in Oklahoma.

So this Thanksgiving, while you take part in that grand American tradition of trying to stay awake at 4 in the afternoon to watch the football on the television because you have a belly full of turkey, give a thought of thanks to the Native Americans. Not only were they the first Americans—and not only did they save the Pilgrim’s asses—they were also the first American footballers. They too have their part in the global history of football. And so, they too have their part in the history of soccer, the world’s game.

Great article. I’m not surprised that the English had a negative version of the game, as long ago as that, or that they despised technique in favor of knocking people down.