How much does the first game in the group stage matter? ESPN has reminded us ad nauseum that 86% of first game winners progress to the knockout stage, while only 8% of first game losers move on. Fair enough, but with so many close results this year (nobody has won a game yet when both teams have scored)*, the question of success after a first game tie is a big one as well.

Since FIFA went to the current knockout stage qualification system in 1998, 59% of teams that tie their first round game have made it to the knockout stage. Paraguay and Sweden have done it twice. The Swedes tied Trinidad and Tobago in 2006 0-0 and tied England 1-1 in 2002. Paraguay tied South Africa 2-2 in 2002 and Bulgaria 0-0 in 1998.

The 2010 World Cup has already seen more first game ties than ’98, ’02, or ’06 and two groups have yet to play

Leaving Germany’s dominance aside, the obvious question to ask is why teams in the 2010 World Cup cannot hold a lead. Only South Korea and the Dutch have put in the crucial second goal that good teams usually grab, a goal that has been referred to as a dagger so many times that it should be represented on Gamecasts with tiny sword clipart. South Africa, England, Paraguay and Slovakia have all been found lacking when asked to finish off a game. And, curiously, only Slovakia has looked as though they were pushing for a second goal (and only in spurts). The rest seemed content to sit back and defend.

This mentality has been a long time coming and, incredibly, the story behind it begins and ends with Jose Mourinho.

The Special One won the 2004 Champions League final with Porto by playing a 4-4-2 built to counterattack. Deploying what amounted to four central midfielders behind a sitting striker and Carlos Alberto, Mourinho deigned to let Monaco attack. The theory can be summed up in basketball terms by the cliche, “There are good shots and bad shots.” In soccer there are spots on the field that players like to go, and there are types of crosses and types of passes that teams like to play. If you can force a team – even a very good team – into unfamiliar positions, you have the advantage. It is up to your defenders to win the less-than-ideal crosses and the obtusely angled through-balls that come in.

Porto played the system perfectly, as evidenced from Monaco’s seven first half offsides. While the French side held 54% of possession, they managed only a single shot. And in the 39th minute, Porto counterattacked through an outside back, Paulo Ferreira, whose cross found Carlos Alberto after bouncing around the box.

All well and good, but counterattacking football has been around since… well, since attacking football. So what’s the big deal?

The big deal is the second half. Monaco had 58% of possession, 5 offsides, no shots on goal, and Porto committed 8 fouls but received only a single yellow card. Mourinho’s theory was that he could allow Monaco to possess the ball, provided that they remained in unfamiliar positions. It’s a very basic footy idea, but you have to truly understand the other side’s strategy to make it work.

Porto made the holding midfielder distribute and forced Monaco’s wide strikers to collect the ball in advanced positions where they didn’t have room to run at defenders. Two things made this system work: 1) Porto never stopped counterattacking, and 2) Mourinho is a fantastic coach, and his players often know the other team’s system better than the other team.

Mourinho added a new wrinkle when he moved to Chelsea. With Didier Drogba, he had a striker who gave his offense two dimensions. While Chelsea could still counterattack with the best, Drogba’s ability to hold the ball alone meant that the Blues could develop a possession offense around the big Ivorian through the wing play of Arjen Robben. Chelsea lost one game in Mourinho’s first year and tied 1-1 only twice. When Chelsea got a lead, they did their best to finish the game off.

With Mourinho’s success, the system he built filtered down through the footy world. The one-striker system gained prominence in the EPL and many teams took other cues from Porto’s Champions League win. Noting the high foul total in the match, managers have realized that if you foul early and often, you get more leeway before the cards start a-comin’. This type of rough play only works if it starts from the opening whistle, but it can completely stifle a strong passing attack (lookin’ at you, Wenger).

Barcelona was the first to develop a gameplan to combat The Mourinho. They started by purchasing Giuly, the player who gave Porto the most trouble in the final. Then they brought in Deco, the playmaker at the heart of Porto’s counterattacks. By pairing Deco with Xavi Hernandez, Barcelona planned to move the ball quickly and efficiently, while stretching the length of their passes. They devised a system in which off-the-ball movement took extreme precedent over dribbling until deep in the final third of the field, an ironic choice considering two of the three best dribblers of the 2000s have worn the blue and red jersey. But Barcelona needed to speed up the game in order to get key men like Ronaldinho and Eto’o into their most dangerous positions. Once those guys were in good positions, they could dribble all they wanted.

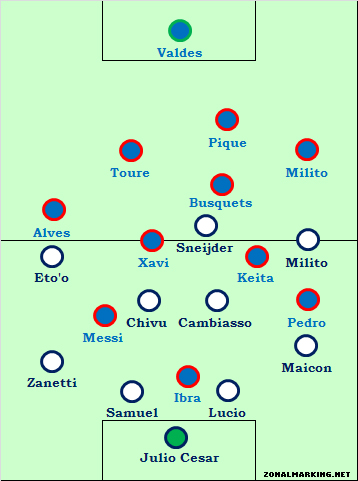

Thus Barcelona ruled Spain while Mourinho ruled England, then Italy. And, wearily, we arrive at our climax: The 2009-10 Champions League meeting between Mourinho’s Inter Milan and Barcelona. Mourinho finally had the players to run his system, bringing in playmaker Wesley Sneijder to feed strikers Diego Milito and Samuel Eto’o. Although Inter fell behind Sneijder pulled them level 11 minutes later off a Milito pass, and then it was Milito’s ability to hold the ball that allowed Maicon the time to get forward and finish the go-ahead goal. Milito would top off his brilliant display with a headed goal off a counterattack.

But the first leg of the semifinal isn’t our focus. We began by discussing how to hold a lead, and to this topic we must return. Inter needed to hold a lead against the most talented offensive team in the world, and to spice things up, they went down to ten men after 27 minutes. So a man down against the defending Champions League winners, Mourinho’s Inter went into a shell. They stuck at least nine and often ten men behind the ball and forced Barcelona into (say it with me) unfamiliar positions. Barca doesn’t like to take the ball into the corner and cross it, they want to cut inside and shoot.** And they don’t want Keita taking their shots, they want Messi and Pedro shooting, or at the very least Ibrahimovic. It was a stunning sight to see Barcelona languidly moving the ball in a semicircle around the 18-yard box, uncertain of how to attack. And this memory seems to be etched into the mind of so many World Cup managers. Establish a lead, then sit back and absorb the attack. But this theory has oh so many problems.

First of all, Inter is a team of great players who spend most of the year together. International teams, particularly at the beginning of tournaments, lack the cohesion necessary to pull off 60 minutes of pure defense. All it takes is one mistake, aka Robert Green,*** to lose your advantage.

Additionally, it takes a great coach to make a team truly understand how the other side will attack. Not just what they like to do, but why they do it and when. In the 2010 Champions League final, Inter snuffed out Arjen Robben because they knew when to send a second defender and how to cover that double-team. Why wasn’t any other team in the tournament able to figure that out? Coaching.

And last, this superdefense technique is counterintuitive. You don’t start a game with eleven defenders on the pitch, and it’s madness to pretend otherwise once you score. There may not be many American football fans reading this, but if you do watch soccer’s lesser cousin you know how frustrating it can be to watch your team go into the prevent defense. It rarely lives up to its name.

As of this writing, 10 of the 13 2010 World Cup matches have been ties or 1-0 wins. Playing for a 1-0 win is like playing for a tie. You give up control of your own destiny and you offer the other team a chance to pull a rabbit out of their hat. You know how to keep the rabbit in the hat?

Stab it with a dagger.****

*Written before Brazil-North Korea.

**Or send in a surprising early cross, everybody who watched the 2009 Champions League final is thinking.

***Yeah, I mean AKA, not e.g. It’s a joke, like his nickname is One Mistake. One Mistake Green, get it? Suck it, language buffs.

****I am the proud owner of two awesome rabbits, and if I actually catch any of you stabbing a bunny I will hire John Harkes to follow you around and commentate on your life while Alexei Lalas chimes in on the hour.

(thumbnail image source: Zonal Marking)

Well played, Cann. Well played.

It’s the modern evolution of the Catennacio and while not as completely ugly on the eyes is just as sapping of the soul.