With an international break overlapping the MLS schedule, both New York City FC and Philadelphia Union had big decisions to make. Patrick Viera needed a stable midfield without Yangel Herrera — on duty with the Venezuelan U-20 national team that beat the U-20 USMNT early Sunday morning — and Jim Curtin needed to replace Ale Bedoya in the middle of the Union midfield. Bedoya is the bigger name, but Herrera’s brief stint in the NYC midfield has provided a solid base from which the exceptional Alex Ring and Maxi Moralez can operate. Viera decided to move Ring into the deeper role so the Finn’s motor could provide cover behind the advancing fullbacks.

The plan worked… eventually.

Key to understanding how NYC maintained control of the match — and regained it after Philly’s brief moment on top midway through the second half — is the way the home side created numerical advantages in the areas near the ball and used their spacing to advance up the wings and smother the Union’s attempts at possession soccer. More specifically, NYC was excellent closing the ball down after losing it, rarely allowing Philly the space they needed to establish a passing rhythm and test New York City’s organization around Ring.

Winning the width

When Toronto FC moved to a three-back system in 2016, they sought to gain better control of the wide areas with wingbacks that made it more problematic for opposing fullbacks to step out of the back. With a wingback flying up the touchline, a fullback has to hesitate before stepping forward to a winger or midfielder on the ball. Toronto’s goal was to spread teams out, which gave them (and still gives them) a leg up when they move the ball across the field quickly. Opposing midfielders must travel great distances to help their far-side fullbacks when Michael Bradley switches play, and as they go they must check the lanes they leave in case Jozy Altidore is checking back into one and prepping to isolate a center back.

New York City has no such pretensions about spreading teams out; their pitch is kinda, sorta the minimum size allowed in the league, and they have to operate in those conditions more than anybody else.

Although this makes expansive play more difficult, it can make building triangles in the wide areas a bit easier. Central players have far shorter distances to travel to join in quick passing moves up the flanks, and opposing defenders find decision-making accelerated.

These combinations occur most often on NYC’s left for a few reasons. First, David Villa loves the left channel, and he can pull a central defender around with him as well as anyone in MLS. Second, NYC has quality depth at left back in both Ronald Matarrita and Ben Sweat. Third, by working up the left, the Sky Blues create space on the right, where Jack Harrison tends to stay wide and look for chances to isolate and attack defenders while Ethan White plays a safe, physical role behind him. Thus, breaking the first line of defense up the left side provides NYC with a host of dangerous options going forward.

How did all of this help NYC control the first half of the match and regain control after Philly’s sucker punch goal? The hosts increasingly looked to advance up the left as the Union front four lost energy and failed to track short, quick runs that broke defensive lines. A typical play unfolds below.

[gfycat data_id=SoreAnchoredAndeancat data_autoplay=false data_controls=false data_title=true]

Notice that Okoli — who receives the long pass from Ben Sweat — starts in the midfield because he has tracked deep to provide numbers around the ball defensively. Once NYC wins possession, Okoli moves forward but not all the way to the offsides line. This forces Yaro to step out of the back line, undoing Philly’s defensive shape. Next, NYC looks to provide runners off Okoli, but the timing is off so both runners are past the striker when he finally gains control of the ball. Still, these immediate runs do two things: First, they once again provide NYC with numbers around the ball in the Union half. Second, these runs push the Union back line deep, stretching Philly’s shape and creating space in midfield. Late in the match, Philly’s front three are slow to recover, so once Okoli controls the ball, he can find Maxi Morales with all the space needed to switch play and provide Jack Harrison with an ideal position to attack the Union defense.

[gfycat data_id=ImmaculateFakeIndianspinyloach data_autoplay=false data_controls=false data_title=true]

Just to drive the point home, above you can see the remainder of that play, which ended with Andre Blake doing his thing… twice.

Importantly, NYC is completely fine with Harrison taking on two Union players on the wing. Morales moves across to take up a position that allows him to press or regain the ball if Harrison loses it. Notice that both Picault and Pontius remain behind the play even as it slows in the final third. NYC earned these chances by wearing down the Union’s wingers all match.

Numbers game

The driving idea behind NYC’s tactical approach is numbers. The Sky Blues want to have a numerical advantage at each level as they advance up the pitch. This starts in back, where they will drop a midfielder into the back line. It continues in midfield, where they look to play direct balls through and move fullbacks and midfielders forward to support the ball. It finishes in the final third, where David Villa provides an eternal outlet from the wing and the far-side winger either stays wide to get isolated or comes across early in the play so the far-side fullback can advance up the pitch.

[gfycat data_id=DisloyalSoggyEarwig data_autoplay=false data_controls=false data_title=true]

What may look like a lucky break — collecting the loose ball after Richie Marquez knocks it down — is actually a result of tactical planning. NYC has three in the back to free up a man for the long switch to Harrison on the right. Then Ring moves out of the back so he’s ahead of Philly’s front three, creating another numerical advantage in midfield. Ring’s long ball doesn’t find Moralez over the top, but the ball still ends up in the space NYC looks to dominate, with both Tommy McNamara and David Villa closer than any Union players. This is all very reminiscent of Pep Guardiola’s Juego de Posicion broad, strategic approach given a more direct flavor to overcome the difference in technical quality between the world’s best players and NYC’s roster.

Switch em if you got em

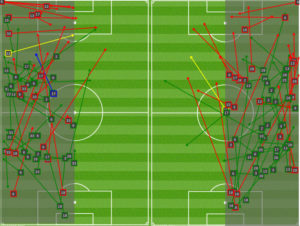

All of this doesn’t explain how New York City so thoroughly controlled Philly’s attack for most of the match. The shots tell the story, however: The Union were thoroughly controlled for long periods. How?

It starts with Alex Ring. The Finnish midfielder drove Philly crazy with his box-to-box play in the teams’ first meeting this year, but this time out he was tasked with protecting the back line.

[gfycat data_id=AcidicPracticalDrake data_autoplay=false data_controls=false data_title=true]

Above you can see Ilsinho at his best as he sends Pontius through up the right. Ring reads the play perfectly though, and he forces Pontius to cut inside early. The Union winger is still in a good position, but he’s no longer picking out an open cross with his dominant foot.

Beyond Ring’s strong play, NYC was extremely successful at preventing the Union from using the entire field. This meant that Philly was constantly operating in tight spaces under pressure.

[gfycat data_id=BeautifulPaltryGermanspaniel data_autoplay=false data_controls=false data_title=true]

In the clip above, the Sky Blues are in position to press the ball after losing it because the place so many men around the ball during possession. Although this leaves the far side of the field open after turnovers, the Union (embodied by Gaddis in this clip) were slow or unable to pick out switches, and often punted the ball back upfield. New York Red Bulls look to execute a similar level of pressure on the ball after losing it, though their attacking approach is far, far more direct than NYC.

It’s worth looking at a longer version of the above clip to see how NYC used their own switches to open up the pitch and attack Philly.

[gfycat data_id=PopularWearyBluegill data_autoplay=false data_controls=false data_title=true]

The play starts with Ring dropping into defense to create space for a long pass out of the back. Chanot picks out Harrison with a pass through midfield, and the winger then moves into the space left behind the Union front three after the rest of Philly’s defense retreats. Harrison then switches fields and NYC quickly pushes players forward to occupy the near-side Union defenders and create a situation where Harrison is taking on Medunjanin in the center with acres of space around him. This is a qualitative advantage because if you’re Patrick Viera you’re probably pretty doggone happy with a Harrison-Haris matchup in the open field.

Union goal

So how did Philly break down NYC to take a temporary lead? It helps to have the best American striker in MLS right now plying his trade up top (don’t @ me, Jozy). Following a turnover, CJ Sapong beat his man to open the field and played a throughball to Fafa Picault that Philly’s attacking midfielders would do well to emulate in the future. It was a simple, quick-hit attack that was likely the only way the Union were breaking through in the second half.

[gfycat data_id=EvilCourageousGordonsetter data_autoplay=false data_controls=false data_title=true]

Final notes: A tactical innovation, a MLS embarrassment

Patrick Viera introduced Ronald Matarrita as a left-sided winger in the second half, though the Costa Rican is a fullback by trade (though an attack-minded one, to be sure). Intriguingly, Matarrita played the position almost like a false nine in a wide area, dropping far into his own half to receive the ball. This drew Ray Gaddis out of the back line, and had the added bonus effect of pulling Jack Elliot — who defended like a center back even after moving to midfield — onto the wing. By leaving the space a winger would typically occupy empty, NYC forced Gaddis and the Union to make novel decisions about how to handle Matarrita.

[gfycat data_id=BronzeFoolishIndianrockpython data_autoplay=false data_controls=false data_title=true]

Above, NYC uses the goalie as an extra man in back to facilitate the buildup play (something that it is difficult for Philly to do because Andre Blake’s aerial improvements mean his feet remain the glaring weakness in his game (a weakness that will make it very difficult for him to start for a top club as the goalie increasingly becomes a necessary pressure escape valve)). Sweat, the left back, collects the ball in a position often occupied by a center back. He finds Matarrita 10 yards in his own half, and Ray Gaddis decides to press the ball. The long sprint forward exposes Gaddis, and Matarrita, excellent offensive player that he is, sidesteps the press and advances the ball deep into Union territory. This is false winger approach fits Matarrita’s skillset wonderfully and it will be interesting to see if NYC can develop this tactic further in the future.

Now… NYC’s pitch. Sure it’s tiny and hasn’t been publicly measured. But an even bigger issue is that a quarter of the field is essentially a grass-covered slip n slide. Anybody hoping to move quickly on the sod covering the Yankee Stadium infield is in for a surprise and a fall. Haris Medunjanin’s free kick slip is only one example of many in this match, and this is far from just a bad day at the office for the sod.

[gfycat data_id=SelfishRealBird data_autoplay=false data_controls=false data_title=true]

It’s bad enough that MLS plays on turf, but playing on a field that makes it look like players are wearing tennis shoes is just horrendous for the league. It sucks, and MLS should be embarrassed each and every day they send players out to compete on that sad excuse for a soccer pitch. This is a professional league, and it should provide facilities that far exceed those used for pickup matches.

Adam, as always, great work. You’ve also tee’d up my piece for Thursday perfectly…

Thanks man! I’ll try not to sneak a peek at your post until it goes live!

That field is such an embarrassment. Definitely doesn’t excuse the Union… I’d like to say “forgetting”, but in reality they have been just bad it since Curtin has been manager… just flat out not marking people on corner kicks. I just wanted to drive home the point on that joke of a field. Great article as always though Adam. Love your work.

It somehow disappeared when Marquez was replaced by Gooch and then came back with a vengeance when Gooch went down. Stopping corners is all about wanting it more. Really hard for me to blame the coach on that.

I missed seeing the match, but that clip of Gaddis high pressing Matarrita a good 10-12 yards in NYC’s half in the 84th min of a tied match on the road while the rest of the backline is 25 yards further back…wow, just wow.

“Ray’s our guy” – Jim Curtin on trading away Williams half a season before drafting Rosenberry (2015). Gaddis may be professional about it all but Curtin has to see his flaws? Right? Right?!

Adam, the above is fantastic as always – specially for those who missed the game like I did.

For those of us whose soccer minds run at a little lower numerical level, I cannot get over the player ratings of a 3 for Gaddis and a 2 for Fabinho from Whisler’s prior article. These were the players that Curtin chose to play as his BEST defenders in these positions.

Does Curtin really believe that these are better grades than Rosenberry and Wijnaldum would have gotten?

It is time to end the sit-Keengan experiment and time to get Winaldum game experience. Neither Gaddis not the Sun Rocket is the future and there is too much tape out there on how to make them look silly

I seriously doubt that Keengan / Winaldum grouping would combine for a sub-5 score.

So maybe there are better ways to defend NYCFC than trying to press at midfield. Maybe stop worrying about crossfield diagonals and just maintain possession with back passes to take the take the steam out of the press. Maybe the UNION conditioning is a little less than optimum. You cant press if you aint real fit. Maybe a little more Italian style defense?