While details remain frustratingly scant, the story of the first professional soccer league in the United States, the American League of Professional Football (ALPF) in 1894, is generally known: Interested in creating a way to make money in otherwise unused stadiums during baseball’s offseason, a group of National League owners created a professional soccer league with teams from Boston, New York, Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. The league proved to be a spectacular failure, lasting only two weeks before team owners decided to pull the plug in the face of generally poor attendance and some $2,000 — approximately $54,000 today — in losses.

What is less well known is the concurrent existence of another professional soccer league, the American Association of Professional Football Clubs (AAPF).

Origins

The origins of the ALPF can be traced to the series of annual inter-city games between the All-Philadelphia team of the city’s Pennsylvania Football Union (PAFU) and the Cosmopolitan team of New York. The series of games against the Cosmopolitan’s had begun in 1891, two years after the founding of the PAFU in 1889. By the time of what was supposed to be the deciding game on February 22, 1894, each team had one win, and while the game would end in a 3-3 draw — Philadelphia would win the replay 4-0 for the “Intercity Championship” on March 24 — more important was the presence at the draw of Arthur Irwin, manager of the Philadelphia Phillies of baseball’s National League.

Two days after the 3-3 draw, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported on February 24 the Canadian-born Irwin, described as “a warm admirer of association football,” had hatched a plan “to have a league of association football clubs composed of professional base ball men.” On June 20, the Inquirer reported, “the American League of Professional Football Clubs was made a permanent organization…backed by the magnates of the six leading Eastern clubs of the National Base Ball League.” The Inquirer reported on August 15 the league had adopted a constitution “built on the same lines as that of the National Base Ball League, but not…so bulky,” with the season to run October 1 through July 1, 1895. The “not so bulky” comment perhaps referred to the fact the six-team ALPF would contain no National League-backed teams from further west than Philadelphia: the Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Louisville, Chicago, and St. Louis teams were not represented. The same day, the Inquirer reported Irwin had been elected president of the league. The Boston Globe reported on September 8 that league play would begin on October 1 with the season now ending on January 1, 1895.

The ALPF was understandably greeted with suspicion in soccer circles. Steve Holroyd, for example, describes in “The American League of Professional Football, 1894” (Soccer History, 2006) the American Football Association (AFA), organizers of the American Cup tournament, viewed the baseball owners as “carpetbaggers.” That suspicion soon became manifest in action. On September 16, the Boston Daily Journal reported a new rule had been adopted at the AFA’s annual meeting in Newark the day before banning any player who “signed a contract and played” with a ALPF team from participating in a AFA sanctioned game. “This course was found necessary because of the action of the base ball magnates, who, it is asserted, are trying to induce association players to join the league.”

Before the AFA’s edict, the Scranton Tribune reported on September 1, 1894 the formation of a rival professional league to the ALPF, the American Association of Professional Football Clubs (AAPF). Clement Beecroft, the inaugural president of Philadelphia’s PAFU, and manager of the All-Philadelphia team that had faced the Cosmopolitans, was named as president of the new league with William Guthrie of Paterson, New Jersey, as secretary and treasurer. And so, with Irwin and the ALPF, and Beecroft and the AAPF, Philadelphia sports figures had a hand in the founding of the first two professional soccer leagues in the United States.

The Tribune report said the AAPF would include teams from Philadelphia, Trenton, Paterson, Newark, New York, and Brooklyn. As was the case with the ALPF, the AAPF did not include sides from some notable locations, with the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, quoting an official from the New York Football Club, reporting on September 3 “the circuit that the professional league has arranged includes all the association foot ball centers in America, barring Boston, Fall River, Pittsburgh, Detroit and Chicago” (the report omits mention of another “foot ball center,” St. Louis). Unlike the ALPF, games would be confined to Saturdays and holidays. The Paterson Morning Call reported on October 2 the league was organized “after the manner of the National Baseball league” and would play “two seasons,” a fall season ending in December, with a spring season running from March through May. The Morning Call report noted, “The clubs have the privilege of playing either amateurs or professionals.” It is unclear if this meant both amateur and professional players could be on a team’s roster or if teams were free to face both professional and amateur opponents. At the time of the report the league was made up of of teams from Philadelphia, Paterson, Newark, and Trenton, although it was “expected that Brooklyn and New York will shortly be embraced in this league.” This would not be the case, however, and the league would include only the single Pennsylvania side and three New Jersey teams.

AAPF plays first professional league game before ALPF

Beecroft’s Philadelphia AAPF team would beat Irwin’s ALPF team to the punch for the honors of playing the first professional league game in the U.S., defeating Trenton 11-1 at Tioga Athletic Grounds in front of about one thousand spectators on September 29, 1894, the Inquirer describing the game as the “first professional game of association football…in this city” in its match report the next day. (A report in the Philadelphia Times on September 21, 1894 previews a game between Beecroft’s team and the the Athletics team of Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood the next day under the headline “First Professional Foot-ball Game” but no match report for the game can be found.) An examination of the Philadelphia team’s roster confirms this was Beecroft’s AAPF team and not Irwin’s ALPF side, as has been reported in later histories of the ALPF. The Philadelphia Times match report published on September 30 described, “It was evident immediately after the opening of the game that the Trenton team was outclassed. It was only a question of how many goals the home club could place to its credit.” In the event, Beecroft’s team scored five goals in the first half, and six in the second half. Fielding players who had previously appeared on All-Philadelphia sides in intercity matches from the Athletics and Tacony teams, the team would generally be referred to in newspaper accounts as “the American Association” Philadelphia team, or as the “Philadelphia Association.”

Contemporary accounts generally did not refer to Irwin’s professional team as the Phillies. Rather, it was referred to in newspaper reports as “the Philadelphia Football Club, of the National Association” or “the Philadelphia National Association Foot Ball team” because the league it played in was backed by baseball’s National League. The Philadelphia ALPF team played its first non-league game on October 1, 1894, two days after the Philadelphia Association team began AAPF play, defeating a “picked” eleven 3-0 at the Philadelphia Base Ball Park, home of the Phillies, at Broad and Huntington Streets, although the Inquirer’s brief report on the game does not say who selected the players on the picked team. The next day, Irwin’s team defeated amatuer side Philadelphia Wanderers, 3–1. Neither of the Inquirer reports give an attendance number. Given that the team’s first two games were played on a Monday and a Tuesday, we can assume attendance was small.

The ALPF season would finally open on Saturday, October 6 — a full week after the Philadelphia Association’s 11-1 win over Trenton — with two games, including a 5-0 road loss to New York for Irwin’s Philadelphia ALPF team. The team hosted New York three days later on Tuesday, October 9, this time losing 5–2. Two days after that on Thursday, October 11, Irwin’s team lost 2–1 on the road to the Washington Senators backed ALPF team at National Park. Still in Washington, D.C., Philadelphia secured its first win in league play the next day, defeating the home team, 3–2, in front of a crowd of 600 spectators.

Interestingly, the Washington ALPF team had deep Philadelphia-area connections. In an October 1 Boston Daily Globe article, Washington Senators owner Earl Wagner said of his soccer team’s roster, “Most of these have played professionally in Philadelphia and Trenton, where the game is popular, but are graduates of the game in England.” An earlier report from the Cincinnati Enquirer on July 31 named five players signed to the Washington team from Philadelphia, and seven from Trenton, on a roster to be capped at 18 players. The reports confirm that, while professional leagues in the US may have been new at this time, professional teams and players clearly were not. Indeed, as Melvin Smith makes clear in Evolvements of Early American Foot Ball (2008) several professional teams were playing in Fall River and Pawtucket as early as 1889. The Inquirer’s claim that the Philadelphia Association’s win over Trenton on September 29 was the first professional game played in Philadelphia might therefore be read to mean the first professional league game.

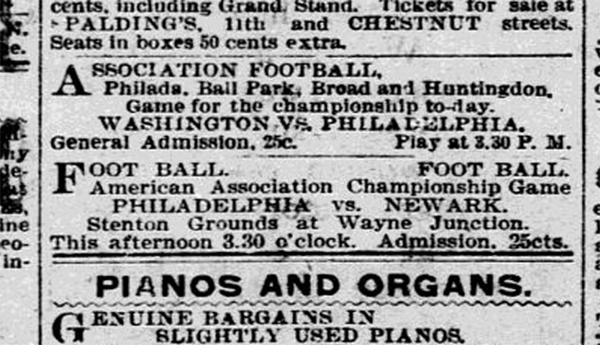

On Saturday, October 13, the Philadelphia ALPF team was scheduled to host the Washington team at Philadelphia Base Ball Park, the same day and time Beecroft’s AAPF Philadelphia team was scheduled to play the Newark team at Stenton in Wayne Junction. In the event, the Philadelphia Times reported the Philadelphia-Washington game had been postponed until Monday, October 15 because of bad weather. The postponement was perhaps fortuitous for Irwin’s side — even though they would have played at home, it would have been the team’s third game in three days, and its fifth game since the opening of ALPF play the previous Saturday.

The Philadelphia-Newark game did take place, however, although the contest was played under apparently controversial circumstances. The teams had first faced each other in Newark on October 6 with the Philadelphia Association returning home the 2-1 winners. On October 11, the Philadelphia Times, with typical hometown hyperbole, described the Philadelphia team as being “considered the finest in this country.” The preview continued,

The Newark boys are determined on this occasion to wipe out their defeat of last Saturday, and on the other hand Manager Beecroft’s team are confident they will continue their unbroken record. Altogether this game will be one of the best exhibitions of Association foot-ball ever seen in this country. Preparations are being made for a large crowd.

General admission tickets to the game cost 25 cents with grandstand seats available at 50 cents, respectively about $6.75 and $13.50 in today’s value. But, with more than a half an inch of rain falling on the city that day, attendance was poor, despite the interest in the game, and the Times reported on October 14, “When Mr. Beecroft got out to Tioga yesterday, he at once saw the gate would amount to nothing, so he decided [to call] the game off.” However, having made the effort to travel to Philadelphia, the Newark team refused to accept the cancellation and lined up on the field. The Times reported, “After scoring a goal the referee awarded them the game.”

Now it was the Philadelphia players turn to make a stand. The Times report continued,

The Philadelphia players then made a demand for their overdue salaries, and that not forthcoming, they gave their manager quite a talk and decided to play the game anyhow. This they did, and won after a desperate fight by the score of 2 goals to 0. The men say they will not play with Beecroft’s team any more, and as they are fighting mad it looks as if he would have some trouble to keep them in line.

Two days after its match report, the Times published a retraction. “Through being misinformed,” it had reported the players had not been paid: “This, it appears, is not true, for the salaries had been paid on the day previous.” The retraction noted that a letter to the paper’s sports editor from “President Fogel, of the Philadelphia Club…shows that the men had been paid right up to date, and that, too, in strict accordance with their contracts.” The Philadelphia and Newark AAPF teams would meet again in Newark on October 20 in a game that ended in a 4-4 draw while, back in Philadelphia, Irwin’s team lost 5-2 to the Boston ALPF team.

The same day, the baseball-backed ALPF announced it had voted to suspend operations a mere 14 days after the league’s opening games. The Washington Post reported on October 21 only Philadelphia’s Arthur Irwin and Washington Senators owner Earl Wagner were in favor of continuing with the league. “Boston, New York, and Brooklyn were opposed to a prolongation, and their votes carried the day.” (It is unclear if Baltimore was not represented at the meeting or if its representative abstained from voting.) A report in the Boston Daily Globe published the same day as the Post report gives some sense of how the ALPF had failed to meet the expectations of its backers, describing “the total gate receipts of the games played in the various cities did not exceed $25” — about $674 today. In the report, “a prominent member” of the league says, “The constitution, comprising the laws and rules which were to govern the contests as issued by the association, showed plainly that the compilers knew very little about their business.” The unnamed source added, “The league also completely ignored the American league, which has its headquarters in Newark, N J, and which has been in a flourishing condition for some time.” The reference to “the American League” is presumably to the AFA, not the AAPF.

After the demise of the ALPF

After the collapse of the ALPF on October 20, the league announced its players would be paid through November 1, although the Boston Daily Globe reported on October 25 that players on the Boston ALPF team maintained they were “entitled to the full amount of their contract,” which was to run “for a season of three and a half months.” With his players being paid until November 1 despite the demise of the league, the Baltimore Sun reported on October 22 that Arthur Irwin had challenged the Baltimore Orioles-backed ALPF team in what turned out to be a series of three games, all in Baltimore. Despite the fact that the Baltimore team had played its first ALPF game on October 17, only three days before the collapse of the league, Irwin’s team lost all three games. The day of its final loss, Beecroft’s Philadelphia Association team defeated PAFU champions Philadelphia Athletic, 7-0.

Despite his terrible record in ALPF play, Irwin said he planned to organize another Philadelphia team. On November 1, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported, “After a great deal of dickering and badgering,” Irwin had finally accepted a challenge issued several weeks before by Clement Beecroft to play a game to determine which of the two professional teams “is entitled to the title of champions of Philadelphia.” The Philadelphia Times reported the same day, “Manager Irwin has made a substantial wager that he has the best team, which Manager Beecroft accepted, and the game will no doubt be for blood as well as coin.” Unfortunately, as of this writing, I can find no record of the match or even confirm that it was played. Perhaps, their salaries now ended, Irwin’s players simply walked. In the event, outside of occasional games taking place at local baseball grounds, Philadelphia’s baseball-soccer connection would remain mute until Connie Mack tried his hand at managing a soccer team in 1901.

On November 10, the Philadelphia Association came back from a 2-1 deficit at the end of the first half to defeat the Paterson professional team 7–2 at Wayne Junction, having first drawn 4-4 on October 20 in Paterson in “a battle royale.” The Inquirer described, “It was in the second half that the Philadelphia Team put ginger into their playing, and remained in their opponent’s’ territory most of the time.”

Thus far, Beecroft’s Philadelphia Association had played other AAPF sides as well as the occasional local amateur side. Soon, Beecroft’s team — and, again, not Irwin’s ALPF team, as has been reported in later histories — would have a part in the early history of college soccer in the U.S. On November 20, the Philadelphia Times reported,

Manager Beecroft, of the Philadelphia Association Foot-Ball Team, received a telegram from Manager Huston, of the Princeton University eleven yesterday, accepting his offer for a game in this city next Saturday afternoon. This will be the event of the season in local association foot-ball circles, as when the crack Tiger eleven meets the champion Philadelphias a fine game is assured.

The two teams had originally been scheduled to take meet at the University of Pennsylvania, but the Inquirer reported on November 21 the game had been moved to Wayne Junction “on account of the carpenters being at work erecting new stands for the Thanksgiving game” of American football between Penn and Harvard on November 29. Princeton had a long football history and in the late 1860s and early 1870s had favored soccer-style football over rugby-style football. But with Harvard refusing to play anything but rugby-style football, Princeton dropped soccer-style play in 1876.

Previewing the match against Beecroft’s Philadelphia Association team, the Inquirer reported the day of the game on November 24 that Princeton was the first American college to form an “association football organization.” Their inexperience was soon evident, and by the end of the first half, Philadelphia was winning, 3-0. Princeton would score a goal in the second half, but Beecroft’s team scored four more to win 7-1. The Times described in its November 25 match report, “The visitors were not in the contest from the time it opened until it closed, as far as making a creditable defense was concerned. The Philadelphians evidently could have beaten them several more goals, and also might have prevented them from securing one goal.”

The Inquirer and Times reports clearly state that the Philadelphia Association’s opponent came from Princeton University, but an article in the December 11, 1895 issue of the Alumni Princetonian suggests the opponent actually came from Princeton Theological Seminary, a separate and distinct institution. The article reports of a game against the professional Kearny Rangers team that took place on December 7, 1895: “This is the second game the Seminary team has played with professionals, the game with the Philadelphia team being lost by the score of 6 goals to 1.” The scoreline for the Philadelphia game is off, but the report nevertheless strongly suggest Philadelphia Association played a Princeton Theological Seminary team, not a Princeton University team. A search of Princeton University’s Undergraduate Alumni Index yields possible matches for only three of the eleven players listed as facing the Philadelphia Association. While the absence of first names or first initials in the Inquirer and Times reports makes a definitive conclusion impossible, the small number of possible matches suggests that, at the very least, most of the players did not come from Princeton University. Further, while there are numerous mentions of association football in the Alumni Princetonian in the years immediately after the 1894 game in Philadelphia, all of those concerning soccer at Princeton involve teams from the seminary, not the university. Indeed, outside of the above quote referencing matches against Philadelphia and Newark, soccer at the seminary itself consisted at the time of informal one-off games or intra-class games. Princeton University would not officially launch a varsity soccer team until 1906. It seems certain Philadelphia Association faced a team from the Princeton Theological Seminary, not from Princeton University.

Beecroft’s Philadelphia Association became the John A. Manz team in 1895, named after its sponsor, the treasurer of the Philadelphia Brewing Company. Beecroft himself fades into history after that. In the meanwhile, the AAPF, America’s other first professional league, seems to have quietly folded. Perhaps it was less a league in a truly organized sense than a reaction to the formation of the APLF, a kind of handshake arrangement among organizers in the leading centers of soccer on the East Coast to stake a claim in the professional game before the “carpetbagger” baseball magnates could dominate the scene. With the collapse of the ALPF only two weeks after its first game, the impetus for maintaining the AAPF may have disappeared and these same organizers could have returned to their previous custom of arranging inter-city contests between leading clubs or picked sides, particularly on holidays such as Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Year’s Day, and Washington’s Birthday, to maximize both interest in the games and gate receipts. Whatever the case, available records show the Philadelphia Association to have been undefeated in AAPF play, playing against teams from Trenton, Paterson, and Newark for a 4-0-1 record, outscoring its opponents 26 goals to 8. By comparison, Irwin’s ALPF side had a 2-6-0 record, the team scoring 14 goals while conceding 31.

While I have been able to document results for the Philadelphia AAPF team against Trenton, Paterson, and Newark sides, I have not been able to locate results for the Philadelphia Association against teams from the two other cities that were reported to be part of the AAPF circuit, New York and Brooklyn. Similarly, I have been unable to locate results of other matches between non Philadelphia AAPF sides. Whether this is a reflection of the sources available to me, or because such matches did not take place, still needs to be determined.

Nevertheless, that the Association of Professional Football Clubs existed in some form is not in doubt and it appears the league both began play before, and outlasted, the ALPF. The Philadelphia Times report on the Philadelphia-Newark game on October 13, 1894 mentions player salaries and contracts for the Philadelphia AAPF team, although specific details, as is the case with ALPF contracts, remain unknown. For example, the mention of salaries suggests AAPF players received regular wages as opposed to per-game payments. Did players earn enough during the week so that playing soccer was their only means of employment? The schedule of the Philadelphia ALPF team suggests this must have been the case for players in that league if only because it is difficult to imagine players would be able to maintain employment in another job given multiple midweek games with associated travel. Was it the same for AAPF players, whose games were played on the weekend?

One thing that is clear is that the AAPF was not the project of the AFA which in September of 1894, as stated above, had banned players who signed with ALPF teams. On December 17, 1895, the Philadelphia Inquirer printed the contents of a letter from AFA president William Turner to Manz manager Theodore Mackenzie that read in part, “At the annual meeting of the American Football Association, all players who played professional football in the National and American Leagues last season were reinstated into the amateur ranks by almost unanimous vote of the association.” The Inquirer report notes, “The Manz team, of Philadelphia, which is composed of the players who represented Philadelphia in the American League is eligible to compete in all amateur events.”

Two of the reinstated players, David Wilson and Manz would defeat Paterson in the deciding game of the American Cup final in front of 5,000 spectators at Cosmopolitan Park in Newark.

Author’s note: I wish to express my gratitude to Steve Holroyd, Melvin Smith, Brian Bunk, Grant Czubinski, and Tom McCabe for their comments and help while I was doing the research for this article, which first appeared at the Society for American Soccer History website on October 21, 2015.

RECENT COMMENTS