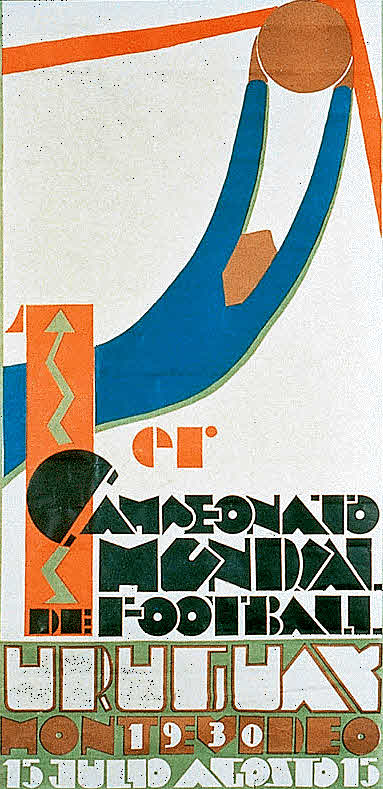

The second part in our series on the US at the World Cup continues our look at the first World Cup in 1930 where the US finished third in the tournament. Along the way, Bert Patenaude scored the first hat trick, and Jimmy Douglas recorded the first shutout, in World Cup history.

The second part in our series on the US at the World Cup continues our look at the first World Cup in 1930 where the US finished third in the tournament. Along the way, Bert Patenaude scored the first hat trick, and Jimmy Douglas recorded the first shutout, in World Cup history.

The US team for the first World Cup was selected after three tryout games. While Wilfred Cummings, treasurer of the USFA since 1921, was the general manager of the team, the actual coaching was done by Robert Millar.

Millar had played for St. Mirren in Scotland before emigrating to the US. In the 1910s he played in Philadelphia for Tacony, Bethlehem Steel FC, and Philadelphia Hibernian. He eventually became a player and coach in the ASL. During the American Soccer Wars he broke from the ASL saying, “You have not lived up to the terms of my contract, which call for me to play and manage under the rules and regulations of the United States Football Association, and by forcing me to engage in outlaw soccer, you are breaking my means of gaining a living.”

While sixteen players were selected for the US squad, the same starting eleven appeared in each of the World Cup matches. These included players from the ASL’s New York Nationals (Jimmy Douglas, Jimmy Gallagher, Bart McGhee), New York Giants (George Moorhouse, James Brown), Providence Clamdiggers (Andy Auld), Fall River Marksmen (Billy Gonsalves, Bert Patenaude), New Bedford Whalers (Tom Florie) as well as players from St. Louis’ Ben Millers team (Raphael Tracey) and Detroit’s Holley Carburetor (Alex Wood).

The only player selected from Philadelphia was also the only amateur on the team. James Gentle played for the Philadelphia Cricket Club though it seems his language skills were more important than his soccer skills as he was the only person in the American contingent fluent in Spanish.

Several players had previous Philadelphia connections. Bert Patenaude played for Philadelphia Field Club in 1928, scoring six goals in eight appearances. Interestingly, all of his goals for Philadelphia came in lots of two, with Patenaude scoring braces against New York Nationals, Brooklyn Wanderers, and Providence Gold Bugs. Patenaude would return to the Philadelphia to play for the German Americans in 1933-34, and with Philadelphia Passon in 1936. While Bart McGhee was with the New York Nationals when he was selected for the 1930 World Cup team, he had a long association with the city, where his family had settled after emigrating from Scotland. He began his playing career with New York Shipbuilding in 1917, a team whose home was, despite its name, in Camden, New Jersey. He then playing for Wolfenden Shore in between 1919 and 1921, Philadelphia Hibernian in 1921-22, and with Fleisher Yarn in 1924-25. In 1929, McGhee made 18 appearances with Philadelphia Field Club on loan from New York Nationals. Jimmy Gallagher had been McGhee’s teammate at Fleisher Yarn and was his teammate again at New York Nationals when both were selected for the 1930 World Cup squad.

On July 1, 1930, after an 18 day voyage by sea that included stops in Bermuda and Brazil, the US squad arrived in Uruguay’s capital of Montevideo where it had rained for 92 consecutive days. While team trainer Jock Coll had worked hard during the voyage to maintain the players fitness, it wasn’t until two days after arriving in Uruguay — and ten days before its first World Cup game — that the players actually played with each other for the first time in what was its first training session in South America.

The participating teams at the World Cup had been organized into four groups, with Group 1 containing four teams and the rest of the groups three teams. The US was in Group 4 along with Belgium and Paraguay.

USA versus Belgium

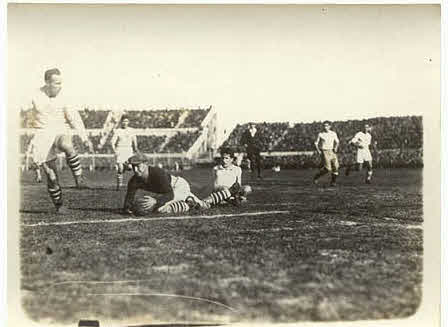

The US faced Belgium on the first day of the tournament on July 13, 1930 at the Estadio Gran Parque Central. The field was wet and heavy after repeated rains and the first snow in Montevideo in five years began to fall as the team took to the field in white uniforms with blue and red horizontal stripes on their socks. For many of the US players, familiar with such conditions from playing during the winter in the Northeastern US in the ASL, it must have felt a bit like home.

In the opening minutes, the Belgians, wearing red uniforms, pressed the Americans with several scoring opportunities. Team general manager Wilfred Cummings wrote in his official report of the tournament,

The first twenty minutes were like hours of anguish, it taking that length of time for the boys’ nervousness to wear off. Our Halfbacks were mis-hitting and our forwards were way off, but fortunately our backs and goalie were unbeatable, successively staving off Belgium’s too numerous chances to convert, they too, being evidently under terrific strain in an endeavor to find their “land legs.”

In the 23rd minute (according to FIFA’s official match report; Cummings says “just passing the first half hour”), a “lightning shot” from Billy Gonsalves struck the Belgian crossbar and rebounded to US left winger Bart McGhee whose first time shot scored the first US goal in World Cup history, a goal that was only minutes too late from becoming the first ever World Cup goal. Cummings reports, “That was all that was needed, for we seemed to immediately snap out of it, and from then on the team was positively unbeatable.”

Just before halftime, Tom Florie made it 2-0 when the Belgians were caught ball watching: Bert Patenaude had intercepted a clearance by the Belgian defense which he then passed to Florie. The Belgians, waiting for an offside whistle, paused, leaving Florie alone in front of the Belgian goal. When the whistle didn’t come, Florie promptly put the ball in the net.

The US continued to attack in the second half, stopped only by some offsides calls, the crossbar and the post. In the 69th minute, James Brown made “a beautiful run” on the right wing. When the Belgian goalie had left his line to challenge, Brown delivered an “unselfish lob over the goalie’s head” to Patenaude, who headed the ball into an empty net. Cummings described it as “one of the most brilliant plays in the entire tournament.”

With the win, US goalkeeper Jimmy Douglas recorded the first shutout in World Cup history.

USA versus Paraguay

Four days after defeating Belgium, the US faced Paraguay in front of a capacity crowd at the Estadio Gran Parque Central. After only ten minutes the US went up 1-0 when Patenaude converted a cross from Andy Auld. Just five minutes later Patenaude made it 2-0 when he beat the Paraguay keeper to a long ball from Raphael Tracey. The US, continuing to dominate in the second half, made it 3-0 when, after a solo run on the left, Auld passed to Patenaude who shot from a few yards out to record the first hat trick in World Cup history.

The US had surprised many with the best record of the tournament coming out of the group stages, and Cummings report makes it clear that the team had quickly become a crowd favorite. Scoring six goals with none allowed, the team was viewed as legitimate contenders for the world championship. One Argentinian commentator wrote,

They all are talented athletes who play a smooth game and use their bodies well although occasionally they commit fouls; they have a remarkable domination on high balls which can be paralleled only by the great British and especially Scottish professional teams, whose way of playing perhaps they follow, but without monotonous precision and with much more vitality and enthusiasm. The full backs get rid of the ball with power and assurance; the midfield line defends, mixing very well with the fullbacks and giving remarkable help to the forwards, who have a wonderful kick that they utilize for passes and for sending high balls in to the goal area to exploit their superior heading capacities.

With no British teams in the competition, the US would meet Argentina in the semifinals as a representative of the English soccer style. Tony Cirino writes in U.S. Soccer vs The World, “The U.S. – Argentina game — a replay of the 1928 Olympics — presented a contrast between two soccer schools: the short passing and polished skills of the South Americans and the athletic game in the air and long balls of the North Americans.” Argentina had defeated the US 11-2 at the Olympics.

The semifinals: USA versus Argentina

The US took to the field at the newly completed Estadio Centenario on July 26, 1930, as the home crowd favorites: every Uruguayan wanted the US to defeat the Argentinians in the first World Cup semifinal. The dimensions of the field – 100 yards wide by 138 yards long – proved to be a challenge to the US players and the team was unable to duplicate its performance in the previous two games. Cummings reported, “The game started with a bang, and while play appeared most even it could be noticed that our long wing-passes were falling short and the usually long kicks of our backs, that generally crossed the half-way mark, were dropping in our own half of the field. The immense size of the playing pitch was treating us badly.”

Four minutes after the opening whistle, a foul on US goalkeeper Douglas resulted in a twisted knee. Fifteen minutes later, a foul on Ralph Tracy injured his right leg. After the game, Tracy would be diagnosed with a broken leg. Meanwhile, the pressure from the Argentinians grew.

In the 20th minute, Argentina scored its first goal. The US fought back only for the injured Tracey to missed two chances, and the half ended with the score Argentina 1-0 USA.

With the injured Tracy unable to continue after the break in this time before substitutions were allowed, the US played the final 45 minutes with ten men. And while the US team, backed by a hobbled goalkeeper, tried to adjust its formation to withstand the Argentinians’ assault, its resolve would not be enough in the face of superior numbers. Between the 50th and 80th minute, Argentina scored four goals.

The match became increasingly nasty and three minutes before time, Argentina scored a sixth goal. In the closing seconds of the match, Auld and Brown combined to pass the ball to Patenaude. Patenaude returned the ball to Brown who then scored the only US goal of the match.

Cummings wrote, “I honestly believe that the Argentinians were a little better team than we were, due to their having played together for many years. However, I believe the unbiased footballer would have given us a good chance to win if we could have kept our eleven players in the game and uninjured.” Millar blamed the Belgian referee for letting the Argentinians get away with dirty play. Billy Gonsalves, “the Babe Ruth of American soccer,” called the game “murder” and said, “They crippled Douglas, deliberately, they broke Tracey’s leg, they hit Auld.”

The injury to Auld — Cummings reports that he “had his lip ripped wide open” after the third Argentine goal — led to one of the great myths of World Cup history. When the team’s trainer, Jock Coll, entered the field to attend to Auld, legend has it that a bottle of chloroform in his medicine bag broke open, so incapacitating Coll that he had to be assisted off of the field. According to Cummings’ official report, “one of the players from across the La Platte River had knocked the smelling salts out of Trainer Coll’s hand and into Andy’s eyes, temporarily blinding one of the outstanding ‘little stars’ of the World’s Series.”

Whatever may have happened in the 1930 World Cup chloroform incident, the US finished third in the tournament when Uruguay beat Yugoslavia 6-1 in the other semifinal game. Since the 1930 tournament, no other team from the CONCACAF region has reached the semifinals.

On July 30, 1930, Uruguay would defeat Argentina 4-2 after being down 1-2 at the half to win the first World Cup.

After the 1930 World Cup

On the way back to the US, the team played a series of exhibition games. They lost their first two matches to the Uruguayan professional teams Central Park and Penarol. In Brazil they played Santos. After being down 3-1 at half time, the US battled back to win 4-3. While the team was in the dressing room after the match, the referee visited with an interpreter to explain “he had been shown the error of his ways and had disallowed one of the [goals] after the game was over, and the score officially would be 3-3.”

The team then played three more exhibition games in Sao Paulo, Rio De Janeiro, and Botafogo, each of which was marked by “scandalously partisan refereeing.” In the six exhibition games they played in Uruguay and Brazil, a total of ten goals were disallowed for the US.

In the years after the first World Cup, many standard histories of the tournament tried to explain away the unexpectedly fine performance of the US as resulting from the presence of six professional players imported from England and Scotland. As Roger Allaway explains in “The myth of British Pros on the 1930 U.S. team“, while there were six players from Britain on the team — five Scottish and one English — only one of them, George Moorhouse, had played with a professional team prior to coming to the US. His total professional experience in England? Two third division games. Of the six players in question, two did play professionally in England — James Brown with Manchester United, Brentford and Tottenham, and Alexander Wood with Leicester City and Nottingham Forrest — but not until after the 1930 World Cup. The rest of the players continued their professional careers in the US, right where those careers had started.

The success of the US at the 1930 World Cup was no doubt related to the relatively weak field of competitors since so many European nations decided not to send teams to the tournament. But the team’s success was also a testament to the quality of the ASL throughout the 1920s. Should the US enjoy a strong performance in the 2014 World Cup, it will in no small part be a result of the growing quality of MLS.

Footage from the 1930 World Cup

A version of the article was first published on April 8, 2010

Thanks for the informative write-up. It seems like the South American squads in 1930 had a serious hate-on for the team from the United States!

It’s amazing that a tournament would actually disallow substitutions, considering the potential for injury in a contact sport. Was that the norm for football in those days?

Substitutions didn’t happen until a lot later, I think in the 50s for the World Cup, and the 60s in England. A lot of matches before that were skewed due to injuries, obviously.

Anyone interested in this kind of stuff should check out “Inverting the Pyramid” by Jonathan Wilson: http://www.amazon.com/Inverting-The-Pyramid-History-Tactics/dp/1568587384

It’s a long but detailed read on how modern soccer came to be.

I’m feeling really upset with Argentina right now, and think that 2014 is the year for revenge!

And can someone make the tournament logo into a t-shirt for me?

This is one of the most informative post I have read relating to the History of the world cup (and I have gone through many). The trainer’s fainting story in the semi-final is a classic, and I have always been curious to find out the truth behind it. This article brings further light to it. Many thanks.

hi!,I love your writing very so much! percentage we communicate more about your

post on AOL? I need a specialist on this area to resolve my

problem. Maybe that’s you! Looking forward to

look you.

Hi there colleagues, how is all, and what you

wish for to say about this post, in my view its really awesome in favor of me.

I recall my great uncle Andy Auld ( who played in all of these USA games ) saying that all referees at the tournament were very , very poor .