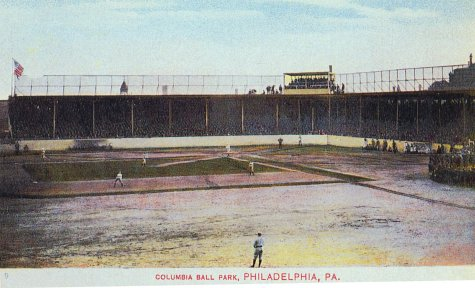

Philadelphia Athletics historian Rich Westcott writes of Columbia Ball Park, “The park functioned as a major league stadium for just eight seasons starting in 1901. During that period, however, it helped to give birth to a new league, was the site of one World Series and was the ballpark in which numerous future Hall of Famers launched their careers.”

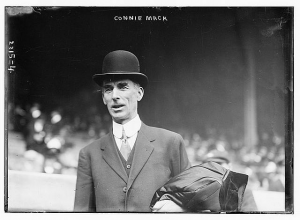

It was also the home of Connie Mack’s soccer team.

When Connie Mack helped to found baseball’s Philadelphia Athletics, an original member of the newly created American League, he and his partner, Benjamin F. Shibe, also built a new 9,500-seat stadium in Philadelphia’s Brewerytown section. Located on a plot surrounded by residential houses and bordered by 29th Street, Columbia Avenue (now Cecil B. Moore), 30th Street and Oxford Street, the stadium opened on April 26, 1901. Westcott writes, “the aroma of hops and freshly brewed beer from nearby breweries often wafted across the stadium.”

On November 28, 1901 the park was the location of the debut of Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Association soccer team in a Thanksgiving Day doubleheader against teams from the Belmont Cricket Club and West Philadelphia Cricket Club.

Earlier connections

Philadelphia baseball stadiums had been the site of soccer games during the long baseball offseason since at least 1890. To mention just a few of the more historic parks, Jefferson Park (North 25th and Jefferson Streets, once the home of the Athletics and also known as the Athletic Base Ball Grounds), Philadelphia Base Ball Park (Broad Street and Huntingdon Avenue, once home to the Phillies and later renamed the Baker Bowl) and Forepaugh Park (Broad and Dauphin Streets and once the home of the Athletics and the Quakers) were all sites of important matches in the early days of soccer in Philadelphia.

The Philadelphia baseball-soccer connection also included a Philadelphia Phillies soccer team in 1894 in the first professional soccer league in the US, the American League of Professional Football Clubs. Aside from the novelty of seeing Phillies baseball players, including future Hall of Famer Sam Thompson, playing soccer, the league proved to be a disaster and folded 18 days into its first season. The Phillies weren’t very good, finishing with a 2–6–0 record in league play.

Seven years later, baseball’s Connie Mack decided to give soccer another go.

“Connie Mack to Boom the Sport”

Soccer in Philadelphia had been growing steadily since the formation of its first organized league in 1889, but the winning of the American Cup tournament by the John A Manz team in 1897 proved to be something of a highwater mark for the sport in the city in the 1890s. The economic crisis that began in 1893 had continued to be severe depression by 1896, and the hard times hit the natural base of the sport—the English, Irish, and Scottish immigrants in the city’s textile and steel-related industries—hard. That, combined with the growing popularity of college gridiron football, the nationalistic atmosphere that accompanied the Spanish-American War (1898), and the anti-British sentiments engendered by the Boer War (1899-1902) made for tough conditions for soccer’s supporters to grow the game. But the sport would soon receive an unlikely local booster.

Philadelphia had long been a center for the sport of cricket in the US, and the area had several long-standing cricket clubs that were themselves centers of society in Philadelphia and its suburbs. In 1901, the Belmont Cricket Club, which had organized a soccer team in 1900, hosted “Mr. B J T Bosanquet’s” touring cricket team from England. Arrangements had been made for an exhibition game of soccer, and the match, Philadelphia’s first international friendly, took place on October 8, 1901, drawing some 2,000 spectators to the Belmont club’s grounds in West Philadelphia.

The event seemed to both return attention to soccer and provide the impetus for the formation of new teams across the city. This was reflected in an article in the Philadelphia Inquirer on October 20 that reported the exhibition game “was the means of arousing a pronounced public interest in a game that was previously comparatively unknown to the sport loving residents of this city, and a number of new local clubs have been organized in consequence, while the ranks of older organizations have been so strengthened that several of them intend putting two teams on the field.”

On October 31, 1901, a little more than a month after the last Philadelphia Athletics game of the American League’s inaugural season and three weeks after the game at Belmont, the Inquirer reported, “The Philadelphia Association Football club was organized last week, with Connie Mack, of the American Base Ball League, as manager.” The article continued, “The formation of the club has been contemplated for some time but the making of the final arrangements was not concluded until yesterday.” The local buzz from the international friendly aside, the baseball-soccer connection seems to have been in the air. On August 30, 1901, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported the formation of the National Football League, which was to feature soccer teams from St. Louis, Chicago, Detroit, and Milwaukee. Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey backed the Chicago team, although the league fell apart soon after its formation was announced.

The Mack’s team would participate in the Philadelphia’s Allied Association of Football Clubs league. All of the team’s games would be played at Columbia Ball Park, which “would be opened every afternoon for practice.” The article said further, “Mack has been very successful in securing a number of old American Association players from all parts of the country…The management have already received several applications for places on the team, any men who have experience with the game will be welcome at the practices with a view of their getting on the team.” Presumably, the reference to the “old American Association” was to the American Football Association, the organizer of the American Cup tournament. The AFA had suspended operations in 1899 because labor strife caused by the ongoing economic conditions had affected the participation of many member clubs, as well as creeping professionalism resulting in disputes between clubs. The AFA and the American Cup tournament would not return until 1906.

Off to a good start

On November 24, the Inquirer reported that some 500 people showed up to watch an inter-squad game between two teams composed of players on Connie Mack’s team. The attendance of so many people to a meaningless game was a good sign, and the Inquirer reported on November 29 that the Thanksgiving Day double header “drew very well” at Columbia Ball Park. The first match, a 10:30 am kickoff against Belmont Cricket Club featuring two 25-minute halves, “was witnessed by a large crowd of spectators” who saw a Connie Mack side containing “recruits from several of the leading clubs” win, 1–0. Making only four lineup changes, the Philadelphia Association went on to win the afternoon game of two-30 minute halves against West Philadelphia, 3–1.

On December 7, Connie Mack’s team drew 1–1 with Norristown. The Inquirer reported on December 8, “Every man on Mack’s team played as if his life depended on the result, and as the Norristown men seemed to be in the like mood the result was uncertain until the last minute of time.” The debut of the Linden team at Columbia Ball Park on December 14 proved “some what disastrous” as they lost 3–1, although the Inquirer’s match report on December 15 said, “Mud and wind were two important factors in the game.”

A “good crowd” was on hand when Connie Mack’s side made it two wins in a row when they defeated Nicetown on December 21. The Inquirer reported on December 22 that “the match was a good one to watch and play throughout was very exciting,” but “the superior conditioning of Mack’s men began to tell” in the second half after a scoreless first. They went onto win 2–0.

“A great deal of friction”

When Connie Mack announced the formation of his soccer team, it was also announced that all of the team’s games would take place at Columbia Ball Park. This was natural enough if one of the prime motives for forming the team was to earn revenue from the park during baseball’s offseason. But other soccer clubs had engaged parks of their own for the season. Ahead of the Christmas Day match between Connie Mack’s side and Thistle, the Inquirer reported on December 24, “There has been a great deal of friction between the Philadelphia Association, better known as Connie Mack’s team, and the management of the more prominent clubs over the playing of home and home games, clubs having private and enclosed grounds not caring to give Mack’s representatives both games on the Columbia Avenue grounds, even though a liberal guarantee be offered to them. There is always the idea that a better ‘gate’ can be secured on the home lots.”

Thistle, “the largest organization in the city,” was among those who objected, “having secured Washington Park for the entire season, at considerable expense.” The Inquirer reported, “After considerable trouble, Mack has been prevailed upon to break his rule and consented to meet the Scotchmen at Washington Park on Christmas afternoon.” With both teams undefeated (Mack’s side was 3–0–1 and Thistle was 3–0–3) and “owing to this controversy,” the Inquirer expected that fans would witness a great rivalry in the making.

Fans responded to the hype, and some 2,500 spectators showed up on Christmas Day to watch the match. While the Inquirer reported on December 26 that the Washington Park ground “would have made a far better skating rink than a football field,” spectators saw “two of the fastest Association Football teams in the city battle for supremacy.” Connie Mack’s side was forced to field substitutes after two of their starters failed to show up, but they battled Thistle to a 2–2 draw.

With the Inquirer reporting on December 27 that their stock had “gone up many points after their exciting draw game with Thistle,” Connie Mack’s side was next scheduled to host Eddystone on December 28. But on December 29, the Inquirer reported that the match had been cancelled, “the grounds at Columbia Ball Park being in such a condition that it was absolutely impossible for the players to secure foothold.” The Inquirer also reported that day that “representatives of the All Scotland Association football team of Newport News, Va.” to arrange a game against the Philadelphia Association team on Washington’s Birthday. The All Scotland team, the Inquirer described, “is composed entirely of Scottish-Americans and holds the championship of the South, having won the Southern Association Football League Cup three years in succession.”*

Connie Mack’s team lost their first game on New Year’s Day, 1902, falling to Camden 2–0 in a game the Inquirer reported on January 2 to have “had a tendency to be somewhat rough, both sides being frequently penalized.” On January 4, they drew 1–1 with Trenton.

Disappear into history

The Inquirer reported on January 11, 1902 that Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Association team would face an All-Philadelphia team that day. What the result of that game was, or if it was even played, I do not know because after that report Connie Mack’s team disappears from the pages of the Inquirer. The Philadelphia Times also does not have a report on the January 11 game, but it does report that Mack’s team defeated Thistle at Columbia Ball Park on January 18, 1-0. The Times report notes that “By far,” this was “the largest attendance seen this season.” On January 25, Mack’s team won again, defeating Wayne, 1-0. At this time, the Philadelphia Association was in fourth place in the Allied league with a 7-1-0 record.

Reports in the Inquirer of any games between local soccer clubs basically vanish for the remainder of the 1901-1902 season. Listings the Philadelphia Times show Mack’s team was scheduled to play Belmont on February 1, Delancey on February 8, and host Norristown on February 15, but the paper has no match reports for those scheduled games.

It seemed odd that reports on soccer should disappear so completely from the record, particularly since as late as December 28 the Inquirer was reporting that 17 teams had joined the newly organized Allied Association Football Clubs of Philadelphia with four more ready to join “at the next regular monthly meeting.” So, on a hunch, I decided to take a look at the historical weather data for the city on the Franklin Institute website, which has weather information for the city going back to 1876.

Looking at the 1902 data for January 1 through April 30 for 1902, while it appears that temperatures were generally relatively mild, the city had to contend with some 13.37 inches of rain and 2.53 inches of snow. While that isn’t a huge amount, much of it seemed to fall in the days immediately leading up to or on Saturday game days. Only four out of 13 Saturdays between January 1 and March 31 saw or were preceded by clear weather but those four game days appear to have been some of the coldest days. Three of the four Saturdays in April were clear, but the second Saturday followed five straight days of rain.

So, during March through April, were pitches largely unplayable, being either waterlogged or frozen? And, as far as Connie Mack’s team was concerned for April, were games not played at Columbia Ball Park late in the soccer season so that the field could recover in time for the start of the baseball season?

A definitive answer is unclear, but a passage from the 1905 Spalding Guide might offer more clues. Describing the boom in interest in soccer following the first international friendly in Philadelphia, C.P. Hurditch writes,

Professionalism once more crept in, however, and the organization owned by Connie Mack, of base ball fame, comprising a number of the best players in the city, tried to make a financial success of the sport. Although they played a strong game all through the season, and were only once defeated, cold, frosty weather, however excellent for players, is hard on the spectators, and the number of enthusiasts who attended paid admission matches was not sufficient to maintain such a team, so the Philadelphia Association team became disbanded, and their members joined various clubs the following year.

Soccer becomes football

What happened to Connie Mack’s soccer team? If it had been formed to make offseason revenue, perhaps it had not met expectations. Perhaps Mack didn’t want to deal with the hassle of clubs with their own grounds demanding that his team play away games. Or, perhaps the success of the Athletics baseball team lessened the need for such endeavors. Winning the American League pennant in 1902, season attendance at Columbia Ball Park was 442,473, more than double the first year figure of 206,329.

Or, maybe it was that Connie Mack had decided to try his hand at professional American football in the first National Football League. It would prove to be an ambitious title for a league that started the season with six teams—all from Pennsylvania—and finished with three. His team, which featured several baseball players, would defeat the Philadelphia Phillies team 6–0 at Philadelphia Baseball Park on October 18, with the Inquirer reporting on October 19 that the team won $1,000 for their effort. They closed the season on December 6 against the Phillies with a 17–6 victory for the city championship, a week after losing to the Pittsburgh Stars. The Stars would be named league champions, a decision no doubt made easier by the fact that David Berry, their manager, also happened to be the league president.

The first NFL quietly folded following the 1902 season. Connie Mack’s American football team would play two games in 1903 before disbanding. Meanwhile, soccer in Philadelphia would continue to find its place in the city’s sports landscape.

–0–

*After this article was first published, Washington DC soccer historian Grant Czubinski kindly alerted me to a match report from the May 11, 1902 edition of the Washington Post on a game between “the Blackburn Rovers, Connie Mack’s all-professional association football team” and the “Newport News Athletic Association” on May 10. The report says the Rovers lost, 2-1, adding, “The winners claim the championship of the country for the association game.” I have since found another very similar report in the May 12, 1902 edition of the Richmond Times.

The Washington Post and Richmond Times reports are the first, and only, reports I have seen linking Mack to the Blackburn Rovers, a team that was a member of the Allied League at the same time as Mack’s Philadelphia Association.

A report in the Richmond Dispatch from May 15, 1902 says that Blackburn Rovers would play the Newport News Athletic Association team again on May 30. However, I have not been able to find a match report in the Philadelphia, Virginia, and Washington DC sources that are available to me to confirm the game took place. Interestingly, the Richmond Dispatch report makes no mention of Connie Mack being connected to the team, although it does describe it as a professional team.

So, was Blackburn Rovers “Connie Mack’s team”? I believe not.

I believe the Philadelphia Association-Newport News Scottish-Americans game scheduled for Washington’s Birthday on Feb. 22, 1902 was not played. Reports concerning Connie Mack occur pretty much year-round in Philadelphia papers at the time and I would expect to find a report if an intercity game involving his soccer team was played (although such expectation all too often are not met when it comes to early US soccer history).

I believe Blackburn Rovers then replaced the now defunct Philadelphia Association team on the bill for the May 10 game. Perhaps the Washington Post and Richmond Times reports on the May 10 game (again, the only reports I’ve seen connecting Mack to the Blackburn Rovers) simply mixed up the background behind it — that Connie Mack’s team was the first choice for the game — and incorrectly associated him with Blackburn Rovers. That the May 15 Richmond Dispatch report on a re-match being scheduled makes no mention of Mack being connected to the team, I believe, supports this.

I also believe that Blackburn Rovers would have had Columbia Ball Park as their home ground if Connie Mack was backing the team. Instead, their home ground was located at Broad and Jackson Streets. Part of the motivation behind Mack forming the Philadelphia Association team was to earn revenue at Columbia Ball Park during the offseason. So, if Mack backed the Rovers, I would have expected them to play there. Instead, their home grounds were elsewhere.

In the event, the Blackburn Rovers appear to have dropped out of the Allied League after the 1902-1903 season.

You rule…

love the history articles, these things are great

My spouse and I stumbled over here different web address and thought I might as well check things out. I like what I see so i am just following you. Look forward to looking into your web page repeatedly.